Almost every reader on the planet is familiar in some way with the epic “1,001 Nights.” We know of Sultan Shahryar, who, heartbroken by his wife’s infidelity, remarries every night only to kill his new bride at the first break of dawn.

That was at least his plan until he marries his vizier’s daughter Scheherazade. Gifted with an unmatched ability to create exciting story plots, Scheherazade succeeds in saving her life and that of other women.

She tells the sultan exciting stories over the course of several nights until she bears him a child, and hence, as mother to the heir of his throne, asks for Shahryar’s mercy. Throughout the 1,001 nights, readers are entangled in thrilling stories of the East.

But how many of us have heard of the collection’s smaller sibling? Only 17 stories long, “101 Nights” offers tales replete with flying horses and every kind of miracle that one could imagine, each so exciting that it creates “a whole cosmos of its own into which we and listeners alike are drawn,” explains Claudia Ott, the translator of a recently discovered manuscript of this medieval Arabic story collection, in a lecture held earlier this month.

“Who, centuries before Leonardo da Vinci, described to us a wooden flying machine with a takeoff and landing propeller, and with what are certainly the oldest motion detectors in the history of literature?” asks Ott.

Where else can one learn about what the merchants of Qayrawan and the cannibals of the Camphor Island have in common, or catch cunning wives at love play with their passionate lovers, and, in the next moment, witness battles with knights and warriors?

Ott — a scholar, musician and professor at the Institute for Non-European Languages and Cultures of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany — says the answer is “nowhere.”

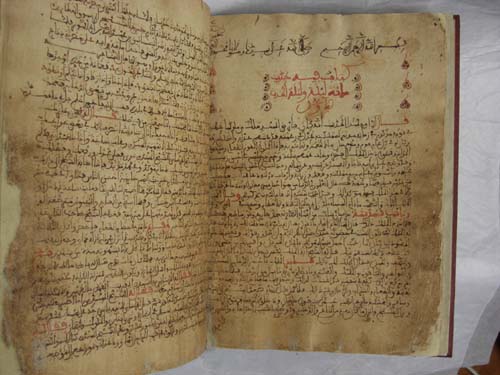

She has previously translated the oldest surviving manuscript of the “1,001 Nights.” But in 2010, when her eyes fell on a beautiful Andalusian manuscript, adorned with red ink that read “The Book with the Story of the 101 Nights,” she was mesmerized.

She was playing the flute at the opening reception of “Treasures of the Agha Khan Museum: Masterpieces of Islamic Art” in Berlin, and saw the 1234 manuscript exhibited in a vitrine with other objects from Andalusia. The handwriting was legible, and all 39 pages, except the final one, were well-preserved.

She asked for permission to take a closer look when the exhibition was being dismantled, and, after verifying it was an original, began translating it the same day into German. Prior to her discovery, other reports and manuscripts of the collection dated back to the 17th century at the earliest.

This discovery is a great enrichment to world literature, she says.

“101 Nights” is not simply an abridged version of the well-known “1,001 Nights.” In fact, Ott explains, the collections have only two stories in common — “The Ebony Horse” and “The King’s Son and the Seven Viziers,” popularly known as “The Book of Sinbad.”

What is most exciting about the “101 Nights” is its geographical origin and the fantastic setting of its tales. All seven preserved manuscripts of the collection come from North Africa and Andalusia, and some of the characters point to the history of the Western part of the Muslim world.

In the first tale of the “101 Nights,” we meet a trader from Qayrawan, Tunisia, and Umayyad caliphs are repeatedly referenced throughout the collection. In fact, Caliph Abdel Malik bin Marwan and his three sons enjoy a similar status in the “101 Nights” as that of the Abbasid Caliph Haroun al-Rashid in the “1,001 Nights.”

This, Ott explains, is due to the historical role played by the Umayyads in the history of Andalusia, and the emirate of Cordoba being considered the successor dynasty of the fallen caliphate of the Umayyads in Damascus.

So, even though the “101 Nights” is set in the faraway kingdom of India, the fascinating setting comes off more like a stereotypical backdrop rather than possessing any geographical or historical magnitude, says Ott.

“It is certainly not by chance that this backdrop has something Oriental about it when seen from an Arabic perspective. It is an image of an Orient that is far away, unfamiliar and exotic — for this reason, particularly attractive,” Ott says.

This was the farthest and hence most exotic setting imagined at the time. And part of the popularity of the “101 Nights” in its era, argues Ott, is that it took its readers and listeners, as they were commonly told out loud by a storyteller, from the furthest West in Andalusia to the extreme Eastern point of the Islamic world.

“If this play of ideas is permissible to the Orient of the Occident of the Orient,” says Ott, “this opens a whole new set of possibilities in the research on world literature.”

For now, the collection is available in German, translated and edited by Ott so as to have readers and listeners alike see the narrator standing before them on a street corner, in a coffeehouse or in an orange grove, the way they were meant to be. In fact, she checked the viability of her translation by reading it out loud to a group of friends and children and getting their feedback. The collection may soon be available in translation to readers worldwide — and better known even in the Arabic-speaking world, where only a few copies remain available. That is how it was meant to be, part of popular culture rather than just being confined to the circles of academia and conservationists, explains Ott.

Claudia Ott gave her talk, "The Hundred and One Nights and its Newly Discovered Andalusian Manuscript of 1234," as part of the "In Translation Lectures Series" organized by the American University in Cairo's Center for Translation Studies.

Image copyrights: Claudia Ott

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.