This year’s International Forum for the Arab Novel, the fifth in Cairo, asked as its central question, “The Arab Novel: Where is it Going?” and yesterday’s symposium on television and literature borrowed from that general theme, asking, “The Egyptian Drama: Where is it Going?” Held at the Supreme Council of Culture, the panel attempted to examine the evolution of the Egyptian teledrama, a new of dramatic television series often based on literary novels.

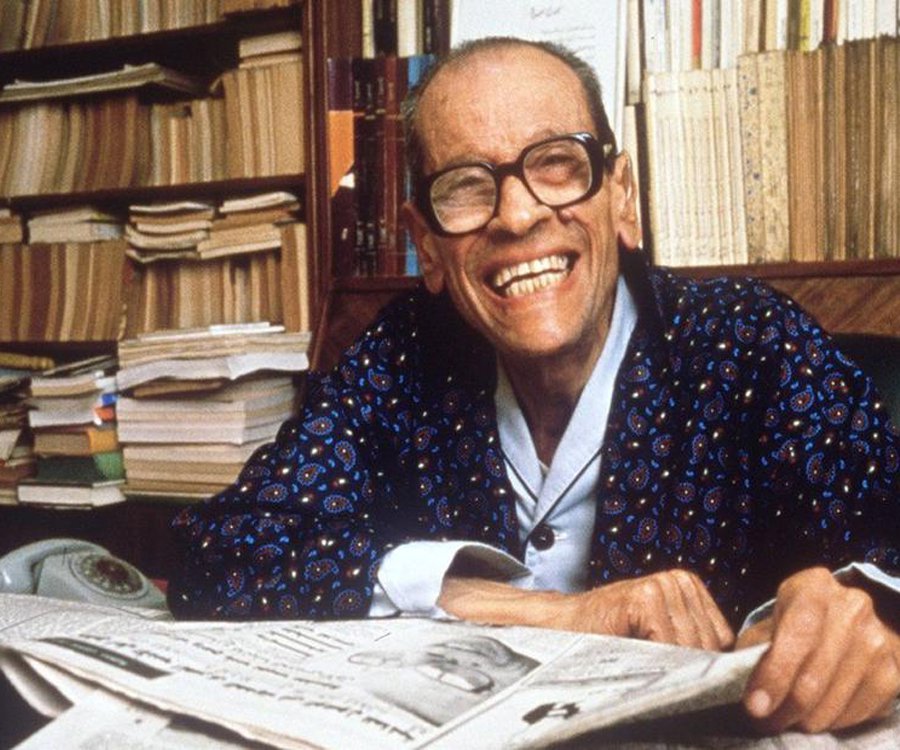

“The Egyptian novel went through major stages of development until it succeeded in leaving its stamp worldwide through Naguib Mahfouz’s novels,” said Hassan Ali, an author and a professor of Mass Communications. Now, the teledrama is making its mark.

According to Ali, the reason behind the great success of this relatively new genre is that it brings novels to life through visualizing characters, events and settings.

Ali listed prominent Egyptian screenwriters as part of the success, including Wahid Hamed, Mohamed Safaa Amer and Galal Abdel Kawy, stating, however, that “Osma Anwar Okasha is the first dramatist who paved the way for the soap opera revolution.”

Okasha, who passed away last May, rose to fame when he created a six-part TV serial called “Laili al-Hilmia” (Nights of the Hilmia). Okasha is now considered one of the most influential teledramatists and authors in Egyptian history.

“The portrayal of Egyptians’ lives and touching upon their problems are the reasons behind his drawing a major audience,” Ali noted.

“Al-Raya al-Beida” (The White Flag), “Dameer Abla Hekmat” (The Consciousness of Teacher Hekmat), “Al-Shahd wal Domoua” (Honey and Tears), “Arabesque” and “Al-Masrawiyeh” (The Egyptians) are among his 40 TV serials.

However, “The quality of Egyptian TV drama is deteriorating,” said Hussein Abdel Rahim, a participating author. Abdel Rahim attributes this to negligence on the part of the government in elevating the artistic taste and preserving its standard.

“The limited budget of Ministry of Culture represents only one third of that of the Interior.”

He added that the same problem occurs with the Egyptian television authority which, according to Abdel Rahim, is represented by only five people who have not changed their approach in years.

“The television officials turn a blind eye to the intense competition they are facing,” Abdel Rahim said. “All they care about is the quantity, not the quality.”

Syrian and Turkish TV serials have managed to occupy a prominent place on the drama scene, gaining a widespread popularity across the Arab world, including in Egypt.

Ali agreed with Abdel Rahim’s criticism of the massive number of soap operas broadcast within the past couple of years during Ramadan.

In researching his PhD, Ali learned that Egypt spent around LE800 million during Ramadan on the production of more than 50 soap operas, “only five of which tackle valuable ideas and are worth watching.”

During the symposium, Ali made the comparison between a printed novel and teledrama, explaining that, “Each one has its own taste and privileges.”

“Soap operas based on novels can easily reach all social classes through television without paying for it,” said Ali.

Broadcasting of soap operas, particularly with the launch of many satellite channels, turns a huge profit compared to the selling of printed books.

On the other hand, “Soap operas require a huge production budget that approaches tens of millions, especially these days when the lead actor receives around LE5 million and sometimes more,” Ali added.

Ali called for the adaptation of literary works into television series, explaining, “The most successful TV series are those based on novels, conveying a meaningful message that respects the intelligence of the audience.