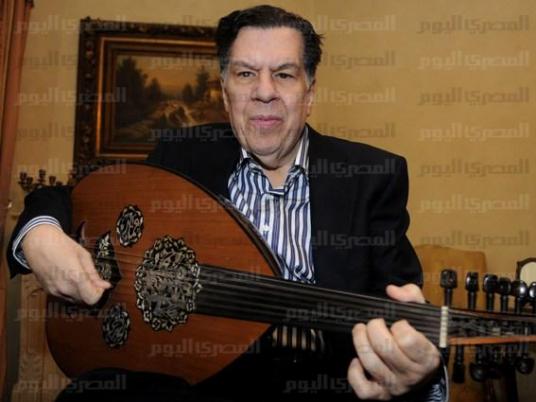

Famous Egyptian musician, composer, arranger and critic Ammar al-Sherei sadly passed away on Friday at the age of 64, after a long struggle with heart disease. It is no exaggeration to say that he was one of the most influential Egyptian composers in modern history. Besides those of the legendary Sayyed Darwish (1892–1923), and the hugely talented Baligh Hamdi (1931–1993), no musical practices presented a comprehensive vision of a diverse Egyptian identity and emanated from its enriching tributaries but Sherei’s.

The man was a well-cultivated composer, with encyclopedic knowledge of Egyptian and Arab folklore as well as the history of modern Arab and Western music. Sherei deployed Coptic, country, southern, Mediterranean, Nubian, Islamic and urban styles effectively in his music. He simply transcended debates of identity and the conflict between Oriental and Occidental music, liberating his music from prejudices and reaching out to people everywhere.

Sherei chose to become a musician against his family’s will. He started after his graduation from Ain Shams University's Faculty of Arts in 1970 as an accordion player, performing in Cairo’s nightclubs, then in the Golden Music Band — one of the most prominent music groups at the time. In 1975, he experimented with musical composition and arrangement, and presented the first song for popular crooner Maha Sabry.

He was one of the pioneers who introduced new developments to the music field, and music instruments to Egyptian artists and audiences. He was also a distinguished oud and keyboard player, and later the first to locally present music works arranged using keyboard sequencers — a fashionable trend in 1980’s.

One of many turning points in Sherei’s life, and possibly the most significant, was losing his eyesight in his early childhood years. However, this was never a handicap. Given his brilliant mind and talent, he grew up as a great lover of life and people, with an inimitable sense of humor and a deeply ingrained desire to learn. He accomplished his music studies through correspondence with the Hadley School for the Blind in America, and later joined the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Sherei helped the Japanese Yamaha corporation develop electronic keyboards that play Eastern tunes, with its unique rubaa tone. Moreover, he contributed to the American Dancing Dots Foundation program Good Feel, which introduces music notation to the blind based on the tactile writing system, Braille.

In 1980, he founded his music band, Al-Asdiqaa (The Friends). With three young rising singers, the band gained wide success offering a totally different music formula. Through his work, he announced the end of the Egyptian lengthy song trend of the 1970s, and took a big leap toward more contemporary, short and expressive sounds. Al-Asdiqaa presented exhilarating, fresh songs that mostly dealt with social critique and young people's views of everyday life in Egypt. Hence, it provided a venue for a rising generation of poets known for their poignant social and political stances like Sayed Hegab, to voice their views through this new attractive song form.

Together with Hegab, Sherei also raised and promoted a new trend of writing songs for TV dramas. In the 1979 “Al-Ayyam” (The Days), a biopic of leading Egyptian intellectual Taha Hussein, Sherei and Hegab presented a parallel song narrative voicing the internal dialogue of Hussein, who happened to be blind too all through his bumpy journey. The experience was a big success, and the artistic duo was able to root the tradition which continues until today.

Along with poets like Abdel Rahman al-Abnoudy, Sherei and Hegab delivered their views and feelings about sociopolitical conditions in Egypt over 30 years through dramatic songs. Those were times when contemporary poetry addressing social and political matters met real difficulties under repressive rule in Egypt, and also had to produce music according to pop music standards. Songs carrying honest political content were quite rare, if allowed at all, with poets pressured to hide behind metaphors to express what they wanted. The chance to ventilate was granted to those poets, only through Sherei’s ability to dissolve hardline poetry into a highly charged and genuine music forms, and relate the whole work to the dramatic context and the soundtracks played in the background.

In many cases during the 1980s and 1990s, viewers became attached to Sherei’s soundtracks more than the actual TV dramas. For people of all ages who have lived through these moments, the music remains memorable, unforgettable and moving.

Sherei worked on the music for more than 150 TV dramas, around 50 films and six plays. He produced albums for early career singers who later became stars like Latifa, Afaf Radi, Hoda Ammar and Amal Maher. He also contributed to the careers of the prominent Ali al-Haggar, Medhat Saleh, Angham and Mohamed Mounir. He was conscious of his role in grooming new talents and mediating music works to the audiences through critique and discussions. In 1988, he started a radio show, “A Diver in the Sea of Music.” Every week, he would select songs and musical pieces for his listeners, highlighting their beauty and weaknesses, explaining musical scales, the use of music instruments, and — above all — presenting a deep and humorous social history of the country, and how it affected artists and music productions.

He stayed away from politics as practice throughout his life, until 25 January 2011. The pronounced composer then addressed TV viewers through a phone call to a television show, in a sorrowful tone and with overwhelming bitterness, asking Hosni Mubarak to leave office. He was one of very few figures who confessed openly that his cooperation with the Mubarak regime — making songs for national celebrations and for the former president — was out of fear and a desire to lead a life safe from danger.

His courageous endorsement of the January revolution through bleak and bright times brought him, however, even more appreciation and love from the public.

Sadly enough, the Egyptian government was reluctant to help in his treatment until he passed away in Cairo.

In his last public appearance in the 9th Alexandria International Song Festival in October — when the ongoing controversy about the role of art according to conservative religious views was heightened — he commented on art’s place in current times.

“It’s the right of our nation that artists make people laugh, even slightly, and cry, even slightly,” he said. “We know better what our religion tells us, and we know that it is our right to live happily and sing.”