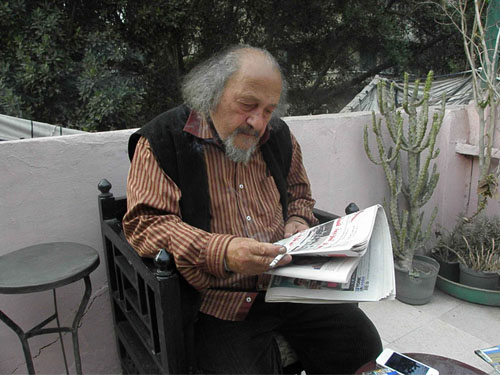

“I feel like I am one of the last remaining people of an Egypt that will soon be dead forever,” says the 80-year old visual artist Georges Bahgory from his studio as he looks down upon the crowded and loud Marouf Street in downtown Cairo.

“You used to have to wear a suit or an elegant dress to walk here. Now ugliness is in fashion, and my vision is polluted.”

But within seconds, his eyes light up as he turns to me and cracks up, seemingly at his own glumness.

“I really love laughing, you know? Laughing and art really are the only way through all of this …” He pauses and waves his hand before adding, “shit.”

Born in 1932 in the small Upper Egyptian village of Bahgora after which his family is named, the artist has witnessed two revolutions, and has been a longtime friend of cultural icons such as Abdel Halim Hafez and Naguib Mahfouz. Bahgory is currently best known for his political cartoons, commonly featured in Egyptian publications over the last half-century, and is referred to as “the granddaddy of Egyptian caricature.” But this label does little justice to his overall artistic legacy and contributions to society.

Upon visiting his studio — which is a time warp with old music records playing and black-and-white photos of a young Bahgory hanging out with the likes of Hafez — it is clear that his artistic production spans political cartoons on paper, but also stone sculptures, large-scale oil paintings, drawings, short stories, children’s books, and beautiful khayameya fabric, among many other things. Room after room, the walls and floors are covered with artworks that easily number in the tens of thousands. Bahgory has many other rooms like these around Cairo and in France, where he has seasonally resided and exhibited for the past three decades.

“For about 50 years, I have worked on my art almost everyday from 10 am until sometime into the night,” he says.

The content of Bahgory’s artwork, when not too abstract, often highlights common aspects of Egyptian culture and history. Om Kalthoum, Hafez and many other musicians, writers, belly dancers and folk instruments are recurring motifs in his work. You also have scenes from coffee shops, streets, and fruit stands, as well as religious symbolism thrown into the mix.

But the beauty of Bahgory’s artistic sensibility lies not so much in the arguably “cliché” content, but in the way these images are combined and portrayed. Unlike much generic “Egyptian art,” his artwork does not exploit these symbols for commercial purposes. It mocks, mutates, degrades and celebrates them all at once, resulting in dark, weird, sardonic, often politically incorrect, but hilarious images. His work is very much anchored in the abstract expressionist, surrealist and cubist eras. He cites Pablo Picasso as his favorite artist, and the influence is clear.

The result of Bahgory’s unique approach is often luring and evocative. One painting he worked on as I walked onto the studio’s terrace shows an overly fat, pink, psychedelic looking Om Kalthoum, singing while crying and somewhat melting into blobby nothingness with the tears. In the background are numerous abstract ornaments, characters and streets.

“This is Om Kalthoum dancing to the ugliness and singing about the destruction of her culture and patriotism,” he explains. However, in the picture she is cheekily grinning and rolling her eyes. “Why?” I ask.

“That is because she knew this decadence was coming, which is why she was so beautiful and sad to begin with,” he says with a laugh.

Bahgory explains that recently his work has come under heavy scrutiny by Islamist groups who claim it is insulting to religion. Many of the works in his studio feature women in niqabs, men with beards and mosques. But he is no longer allowed to feature these in public exhibits.

“They have become banned and considered insulting all of a sudden, as if religion is being invented today and has not been around for hundreds of years.”

“Before I only could not caricature Mubarak himself. Now it is the president and anything or anybody associated with religion, which will eventually be everything.”

Bahgory has an exhibit running at Al Masar Gallery in Zamalek titled “Dialogue of the Mind & Soul.” While the pieces there display many of his signature artistic styles, the selection generally seems to lack the compelling dark satire that makes for some of his greatest work. However, some pieces, such as “The Dancer & the Musician,” which features two sleazy characters grinding together in a dark room, managed to slip through due to the absence of explicit religious content, he assumes.

Because of such censorship, Bahgory is somewhat critical of religious political groups, as well as former President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalism, believing that they are the main “factors behind the ugliness that has become my country.”

He elaborates: “As an artist, my job is to capture the beautiful, amplify it, and share it with the world,” he begins, as he stops working on his Om Kalthoum piece, lights a Cleopatra cigarette and sits down.

“When I was 30, we used to go to Tahrir Square for inspiration. We would see beautiful women and men, from many different countries, wearing beautiful clothes,” he says. “Then they forced out most of the foreigners, neglected the beautiful infrastructure, the men stopped shaving, and the women covered up. Over time, nature and beauty became sinful, and so the conveyors of beauty were slowly marginalized and died out.”

Bahgory believes the Islamist dominance in local politics and increasing censorship will deliver the final blow to this artistic sentiment and freedom.

“Religious people do not care about life and art because they want to get to paradise. Religion prevents them from seeing that we are already there, if we want it.”

Bahgory says that this censorship and obstruction of beauty led to the systemic degradation of the nation's culture, which in turn resulted in an obsession with importing foreign culture, resulting in a loss of pride as well the intensification of cultural divisions within society.

“Now most Egyptians pretend to worship the great artists of the past as if they are part of that history when they are the ones who actually killed it,” he says before picking up a newspaper while shaking his head.

Putting his work aside, the artist himself has a strong presence and affirmation of life that makes me think of the types of characters my Egyptian family used to talk about before migrating abroad. And despite his talk of Egyptian art dying out, visiting his studio, or being in his company, is like entering a time machine to a beautiful time where nothing has changed. The experience was serene, and the chaotic scenes of the streets below fizzled into nothingness as I watched him work and hum along to old French music — so much that when I eventually left his studio, I found myself slightly disoriented back on Marouf Street.

But when asked whether or not he sees any hope for Egypt’s future, particularly with regards to the arts, he believes that “young artists will naturally continue to fight as many are still doing,” and that as living conditions deteriorate, artists may even become better at evolving their art forms.

Using himself as an example, he explains: “As Egypt began to fall apart, my soul began to whither and die. But as a result, my art coincidentally began to become stronger and more poignant. But now there is very little of my soul left. I am dying. And eventually I will die and all that will be left will be my art. Maybe then I can finally join my friend [Abdel-Halim Hafez] in the heavens above,” he jives with a smile, before returning to his painting.