Since the Alternative News Agency (ANA), a workshop and publication project organized by the Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), was first held in 2010, a lot has changed in Egypt, not just in the realm of politics, but also in terms of how we understand and interact with visual media.

The second edition of ANA, which wrapped up last week with a publication launch and a series of lectures, differs from its predecessor in ways that are indicative of an evolving relationship with the proliferating images that shape our understanding of the world.

The original program was focused on production, awareness, and the development of a critical relationship with visual media. But in the time between now and then, awareness of the importance of images has grown on its own accord. Now-iconic photographs such as that of the “girl in the blue bra” have amply demonstrated their ability to spark heated public conversation, and citizen journalism and constant documentation has, for some, become a way of life.

Facing a new relationship with visual media, the second ANA was framed as an opportunity for reflection. Project coordinator Silvia Mollicchi and CIC Artistic Director Mia Jankowicz write in their introduction to the ANA publication: “The shift in global revolutionary politics from hypothetical to actual caused us to seek out experienced practitioners whose work is already having an actual impact on the perception and lived reality of these changing times.”

Rather than creating a program seeking to help shape more critical producers of media, the 2012 ANA program brings together already critical producers, and asks them to make sense of the media that exists.

The resulting publication is a collection of projects, not finished, but captured in a sketched-out form, that seek side narratives and new modes of organization within the mass of media that shapes our reality. The experienced practitioners in the ANA come from a variety of backgrounds — artists, activists, photographers, journalists — and this diversity of approaches helps to create an active dialogue in which, as Mollicchi describes it, “Some contributions are not simply alternative to the mainstream, but alternative to each other.”

Jasmina Metwaly, an artist who over the past year has been heavily involved with the Mosireen media activism collective, capturing and spreading footage of protests and abuses across the web, revisits images that fall into a narrative void, somehow rendered useless, and presents them for examination and interpretation. The emptiness of her images is beautiful but unsettling, and the project reads at least in part as an artist-turned-activist taking a break from the burden of giving images purpose, and in the process interrogating where that purpose comes from in the first place.

Mohamed Elmeshad, a reporter for Egypt Independent, created a piece that, in the context of his work as a newspaper reporter, would have taken the form of a typical profile, but here becomes an open-ended reflection on how to represent someone who has suffered. Elmeshad spent time with Abdelhady Farag, a 21-year-old student who was shot in the neck on 28 January 2011 and is now quadriplegic. He presents Farag’s story in a diffuse format, painstakingly avoiding the imposition of a straightforward narrative onto Farag’s experience, to the point where that lack of imposition becomes the subject of the project.

Elmeshad writes: “The sparse moments when I raised the camera, he was not bashful, nor unwilling, even though he refused to be filmed or photographed in other media that wanted to meet ‘a hero from the revolution.’”

Photographer and web developer Salma Arafa and activist Lilian Wagdy both take existing media and reorganize it to reveal less-visible threads of the events of the past year and a half.

Arafa examined issues of Al-Ahram, Al-Shorouk and Al-Gomhurriya dailies from 25 January to 2 February 2011, tracking the evolution of headlines and front page space distribution, revealing the slow path of realization on the part of the media, particularly government-owned media like Al-Ahram and Al-Gomhurriya, of the enormity of what was taking place at the time. Wagdy collected images of street battles and protests from 28 January 2011 that took place in cities such as Mansoura, Tanta, Suez and Kafr al-Sheikh, showing the breadth of the upheaval of that day, often obscured by the dominating iconic moments of the 18 days.

Nadine Marroushi, also a reporter at Egypt Independent, in comparing Cairo’s battle scars of the last year with those of Beirut, examines the remnants of past violence that remain as unintended monuments, and opens up a conversation on what should be done with those remnants. The strongest example of this is the burnt-out National Democratic Party headquarters, which stands majestically amid the government buildings and hotels that line the Nile. Mohamed Elshahed, who writes extensively on urban matters for the Cairo Observer, tells Marroushi: “The skin of the building should continue to show proudly the marks left by the flames that toppled one of the most powerful and oppressive regimes in modern Middle Eastern history.”

The headquarters present a conundrum: how to repair the space and use it for a constructive purpose, while also maintaining it as a symbol of the rebellion of the 18 days. The building preserves in its blackened shell the recent history of the city, but also stands as a disused wound on the Cairene landscape.

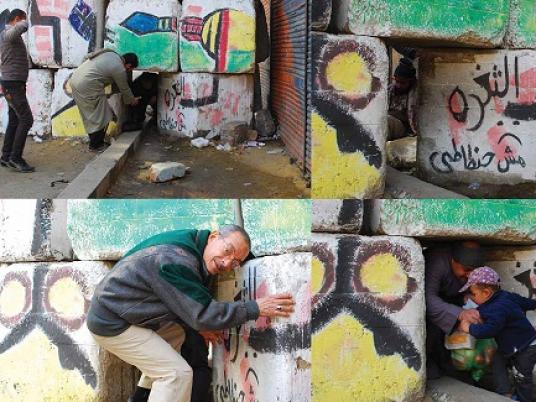

Some projects open up more interesting areas of inquiry than others. Mohammed Allam’s project, a digitally modified image of an army officer in a dress which he sent to a number of artist friends to respond to, is playful but leaves little to think about. Rowan El-Shimi’s project on the downtown walls fails to bring a new perspective to the admittedly dramatic and preoccupying presence of the walls.

None of the artists, journalists, activists and photographers involved in this project has produced finished products. But the publication itself is an accomplishment, a carefully and expertly designed work, thanks to graphic designer Amro Thabit. Thabit incorporates into his design the discursive, unfinished nature of the projects themselves, creating for each its own specific design scheme, even down to the kind of paper used, and visually representing the publication as a gathering of perspectives and ideas in dialogue with one another.

Presented so effectively as a captured conversation, the ANA publication is an accurate and valuable record. The works included carefully bypass the narrative pitfalls that so many projects fall into, and together encapsulate a lively and important dialogue; a dialogue worth remembering.