From the early days of online stock scams to the increasingly sophisticated world of botnets, pseudonymous hacker Peter Severa spent nearly two decades at the forefront of Russian cybercrime.

Now that a man alleged to be the pioneering spam lord, Pytor Levashov, is in Spanish custody awaiting extradition to the US, friends and foes alike are describing the 36-year-old as an ambitious operator who helped make the internet underground what it is today.

“Levashov is a pioneer who started his career when cybercrime as we know it today did not even exist,” Tillmann Werner, the head of technical analysis at US cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, said.

“He has significantly contributed to the professionalization of cybercrime,” said Werner, who has tracked the alleged hacker for years. “There are only very few known criminals that had a similar level of influence and reputation.”

Born in 1980, Levashov studied at High School No. 30, one of the first schools in the Soviet Union to specialize in computer programming. Even at a competitive institution whose alumni went on to universities and Silicon Valley firms, Levashov stood out.

“He did have an entrepreneurial streak for sure,” former classmate Artem Gavrilov said. “He was a leader in school, tried to prove to everyone that he was the best.”

Levashov graduated in 1997, according to an entry published to an alumni website, listing his profession as “websmith” and “programmer.” Within a couple of years he had gravitated toward the burgeoning field of email spam, according to an ad attributed to him in US court documents.

With much of the world still just discovering the internet and few restrictions on the mass distribution of email, spammers more or less operated openly, blasting inboxes with pitches for Viagra knock-offs, online gambling and pornography in return for a flat fee or a cut of the proceeds.

Internet registry records preserved by DomainTools suggest Levashov launched a bulk mailing website called e-mailpromo.com in August 2002 under his real name. Early marketing material for the site boasts of “Bullet Proof Web Hosting,” a term used to describe providers that shrug off law enforcement requests.

The service would come in handy as the spam business became increasingly criminalized. With laws tightening and digital blacklists getting better, spammers resorted to hacking to get their mail across, using malicious software to turn strangers’ personal computers into “proxies,” a euphemism for remote-controlled conduits for junk mail. Hackers herded the proxies into vast botnets, armies of compromised machines that silently churned out spam day and night.

Court documents suggest that Levashov teamed up in 2005 with Alan Ralsky, a legendary bulk email baron once dubbed the “King of Spam.” More than a decade later, Ralsky still raved about the fictitious Severa’s skills.

“No doubt he was the best there ever was,” Ralsky said in a telephone interview.

It was with Ralsky that Levashov is alleged to have plunged into the world of the “pump-and-dump,” a scheme that worked by sending millions of emails talking up the value of thinly traded securities before selling them at a profit and leaving gullible investors to soak up the loss.

Ralsky, Levashov and several associates were indicted for fraud in 2007; Ralsky went to prison while Levashov, safe in Russia, avoided arrest.

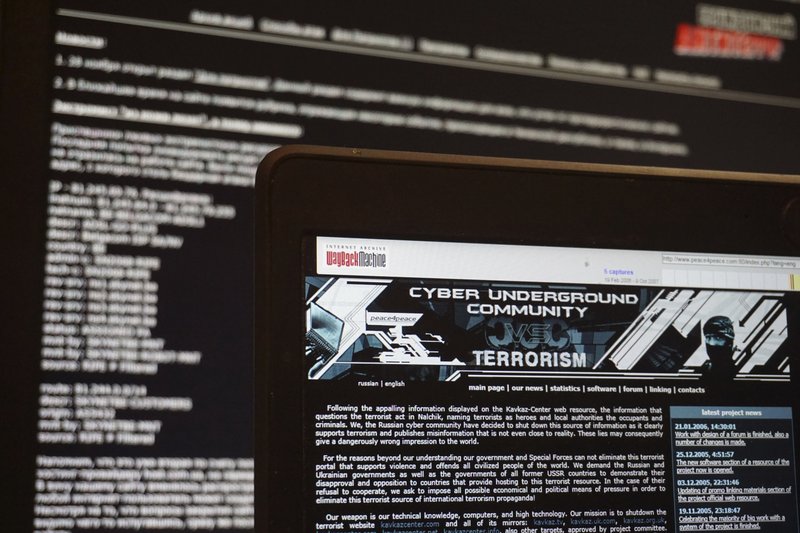

By that point, Levashov was cybercrime nobility in his own right, allegedly running a forum for Russian spammers and the massive Storm botnet, whose sophistication drew global attention.

“There were spam botnets, certainly, before Storm, but it took things to a next level,” Joe Stewart, a security researcher with cyberdefense startup Cymmetria who grappled with Storm at its height, said.

Clever use of peer-to-peer technology and a fast-shifting digital infrastructure meant Storm could be regenerated quickly if part of its network was blocked. Respected security expert Bruce Schneier marveled at its engineering, writing in 2007 that Storm was “the future of malware.”

Storm didn’t go on forever, but two successor botnets, Waledec and Kelihos, have since been tied to Levashov. Indictments unsealed this year accuse the Russian of renting out Kelihos at $500 per million emails to send spam or to seed computers with ransom software or money-draining banking programs.

One of the indictments, which cited a January ad posted to a Russian cybercrime forum, appeared to catch Levashov boasting of his distinguished record.

“I have been serving you since the distant year 1999,” the ad said. “During these years there has not been a single day that I keep still.”

That’s likely to change. Levashov’s Spanish lawyer, Margarita Repina, recently told The Associated Press that her client’s extradition to the United States was all but certain.

Levashov’s wife, Maria, was more hopeful. She has forcefully proclaimed her husband’s innocence, saying he was more of a businessman than a programmer and that whenever she caught him at the computer he was playing video games.

“I believe it will be found that this is all a mistake,” she said.

Then again, in response to a question about Levashov’s links to the Russian government, she said: “I’m not a wife who knows everything about her husband.”