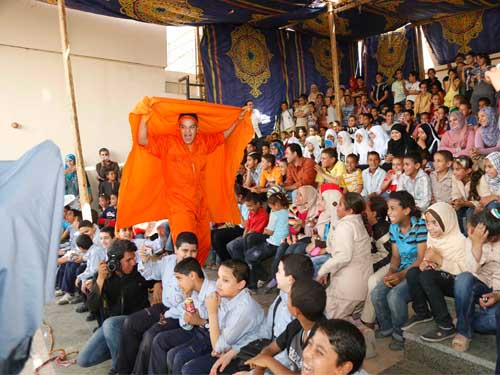

The crowd gathers quickly. In a burst of color and sound, the troupe drums, sings and dances, leading the growing crowd until they settle on a spot. The actors — each dressed in monocolor, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, white and one in gray — create a space around them and encourage those gathered around to sit, ensuring they do not settle too close.

This little negotiation with the gathered crowd, which is now becoming an audience, can take a few minutes. The stage is being created.

This is central to the thinking behind what theater troupe Al-Khayal Al-Shaabi (The Popular Imagination) does. The stage is not something that pre-exists, with lighting, equipment and whatnot. A stage can be anywhere.

Deriving ideas and practice from Poor Theater, Theater of the Oppressed, Bertolt Brecht and others who worked on bringing theater closer to ordinary people instead of it being something for the elite, Al-Khayal Al-Shaabi has been doing street theater since 2002, well before the revolution.

“There is no stage, no lights, nothing — you have to do everything. Of course it is harder, but it is way more satisfying,” says Abdelrahman Adel.

He and Abdallah Mohamed are the youngest members of the troupe. They have been involved for two years now, coming into contact with Mustafa Wafi and Shaker Said, both part of Al-Khayal Al-Shaabi, when they were training them as part of their work at the Jesuit Cultural Center in Ramses.

For each production, the group chooses a theme and a method, and then finds a director. The current theme is revolution, and the method chosen was clowning. The group members improvised for a couple of months, and Spanish director Pepa Diaz worked with them.

“The Colors of the Revolution” was the result, a story of different colors trying to realize their dreams against the oppression of the gray dictator.

Though the production has sometimes been billed as children’s theater, it is not specifically for children.

“It is street theater, so it is for all generations,” Wafi says.

“The idea in all our productions is for the language to be simple, and for it to be really visual,” adds troupe member Marwa Hussein.

Each color tries to realize its dreams, but blocking them is one color, gray. He steals their paint, he dominates them, he forbids them from painting anything. The colors revolt.

And in a twist of one of the revolution’s slogans, “The one who chants will not die,” they shout out, “The one who paints will not die.”

Painting in this story represents not only the capacity to live well but to realize hopes and aspirations. They call out the dictator for oppression, corruption, police violence, bad education — all that led to the explosion of the revolution.

One of the troupe’s early productions, “Ta3l Bos” (Come, Look), which was comprised of five scenes dealing with women’s lives, took object theater as its method. The troupe’s latest production before the revolution, “Corombe Zabadi” (Cabbage Yoghurt, a popular phrase reflecting when things are messed up and confused with one another), was about migration.

Using the buffoon, a type of clown, as its method, it looked at how when we try to escape to go somewhere better, we find that there are hierarchies and oppression there too.

Improvisation is not confined to the initial stages of conceiving the play, however. Given the nature of their work in public spaces, they have to be quite responsive to the crowd — a crowd that varies in size, as people may come and go.

One of the troupe members might decide to jump ahead and start singing a song that comes later to signal to the other actors that they are skipping a bit. They make other changes in rehearsals and through discussions.

The dictator has not been gray for long. Until a couple of months ago, he was dressed all in black. At one of their productions, a member of the audience started taunting a dark girl, associating her with the villain of the production.

“We were also about to do some performances in Nubia, so I think we would have talked about it and changed it, even if that incident with the girl had not happened,” actress Naima Mohsen says.

Little changes are made, in particular with the gray character. He might, for instance, mimic a recent comment made by President Mohamed Morsy or make reference to recent events.

“He is both Morsy and all dictators,” Mohsen explains.

At some point in the production, he mimics a phrase former Libyan leader Muammar Qadhafi delivered in one of his last speeches.

“But really, it is not that we change the play to fit the circumstances,” Hussein adds. “It is that developments in the country keep the play relevant.”

Early last year, the troupe performed in the Cairene neighborhood of Imbaba, but had to abort the performance.

“Some people begged us to stay, but really they should not have been talking to us. They should have been talking to those stopping us,” Mohsen says. “Still, it all happened very quickly, and there were rumors that some Salafis were on their way.”

Mostly, it is not aggression they encounter. Performer Ruth Jurado Castillo recalls going to a village in Minya, when “people of all ages were trying to touch us and pull on our hair. It was not violent, it was just they had not seen anything like this before.”

Sometimes the ethos of the group can clash with the institution that has invited them.

“We talk to staff beforehand, telling them we do not need their interventions,” Mohsen says.

She recalls that with a previous performance at a detention center, “the children did not laugh, and we thought our production was not funny, but actually it was that the children could not laugh.”

“Or that they did not have space to laugh,” Jurado Castillo cuts in.

The troupe has now been doing performances at the detention center for a few years, and their rapport with the children has built.

“Recently, it was hot and a weekend, and the teachers asked if it was OK that they did not attend. And really, it was much better,” Mohsen recalls.

What was interesting about performing there, Jurado Castillo says, “is that the children identified with Shaker, the one dressed in black. When he was being judged, the children were calling for him to be let free, and it was because they were also imprisoned.”

The troupe has performed this production far more widely and frequently than previous productions. At 70 performances and counting, it far surpasses their previous ones, which they sometimes did not perform more than 15 times.

“Before the revolution, it was rarely street theater,” Wafi says. “The performances were open, but often in the premises of organizations or schools.”

While this continues to be the case, the troupe has been able to perform on the street itself a number of times. And they perform in all sorts of institutions, even at the Abbasseya Mental Health Hospital.

Or an audience might be made up of children on a trip with their local mosques, as with their recent performance in Badrashin as part of the Downtown Contemporary Arts Festival, or D-CAF. Mosques in surrounding villages brought the children on minibuses, as they do on other trips, for instance to the fairground or Al-Azhar Park.

At the moment, the troupe is in discussion with someone who has invited them to perform as part of another festival, and has asked them to wear wireless mics.

“We have refused,” Wafi says. “He wants us to perform with mics to an audience of about 5,000, so there would be no audience interaction. He wants us to make an exception, but we cannot. If you do that, you have broken the idea before you have even started the performance.”

“The main change though has been the reactions of people, not the audiences so much as the organizers inviting us. There used to be much more reluctance about all things political and we would be asked to tone it down,” Wafi says.

“Now political criticism and discussion has become much more normal, and it rarely happens these days,” he adds.

“We reach people who would not see theater,” Mohamed, 19, says. “I love it because we go to people, rather than waiting for them to come to us.”