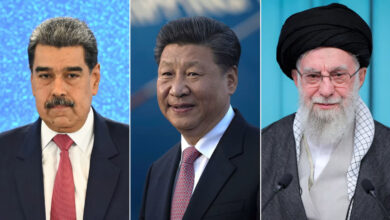

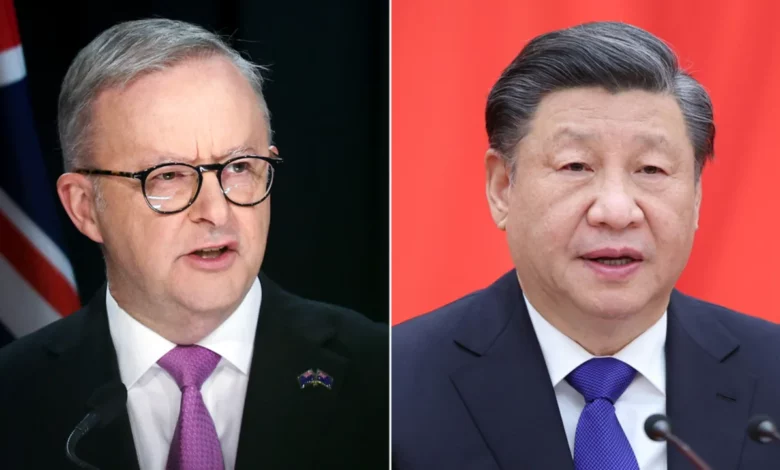

Now, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is headed to Beijing for a landmark trip – the first for an Australian leader in seven years – widely seen as a step forward in both sides’ efforts to stabilize the relationship after years of economic tension.

Stakes are high for the four-day visit, which begins on Saturday and will see Albanese meet with Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang and make stops in Beijing and Shanghai.

The two countries have only in recent months begun to emerge from a diplomatic deadlock that escalated from 2020 when Beijing slapped punishing trade restrictions across a swath of Australian exports.

At the time it was seen as political retaliation for then prime minister Scott Morrison’s calls for an international inquiry into the origins of the Covid-19 pandemic in China, though relations had been deteriorating for some time.

China’s Foreign Ministry blamed Australia for the trade issues, in 2020 accusing it of “violating the basic norms governing international relations,” though its commerce ministry has cited anti-dumping and other reasons for the curbs.

Both sides have much to gain from a step back in those economic tensions, and in recent months have been working hard to pave the way for the trip.

How well the leaders manage the relationship also has important implications for the Indo-Pacific, where smooth communications between China and Australia, a key US ally, could play a stabilizing role in the increasingly contentious region. Leaders from Washington to Seoul will likely be watching closely.

Albanese’s trip also carries symbolic overtones, marking 50 years since the first official visit by an Australian leader to Communist China after the two countries established ties.

A visit to mark that diplomatic milestone represents a step forward in relations, according to Jingdong Yuan, an associate professor at the University of Sydney who specializes in Asia-Pacific security.

“This visit is very symbolic, but still very important. They’ve come this far from the bottom just 18 months ago – this is a good beginning (for them) to explore where they can cooperate,” he said.

Speaking from the northern city of Darwin before his departure on Saturday, Albanese said the upcoming trip was the result of a “patient, calibrated and deliberate approach that we have to the relationship with China.”

“The fact that it is the first visit in seven years to our major trading partner is a very positive step,” he said, according to Reuters.

On the table in Australia-China talks

A range of tensions, however, will cast a shadow over the proceedings. Analysts say the meetings could lay the groundwork for expanded communication, but won’t be enough to turn back the clock on what has now become a fragile relationship.

Beijing’s economic campaign sharpened rising concerns in Australia over alleged Chinese espionage and political interference, its ambitions in the neighboring Pacific Islands, and its detention of Australian citizens.

Journalist Cheng Lei, detained in 2020, was released last month before Albanese’s trip was announced, but writer Yang Hengjun remains in prison since being detained in 2019 on espionage charges, which he denies.

Beijing, meanwhile, has become increasingly alarmed by Canberra’s growing security ties with Washington amid deepening US-China rivalry. China had already chafed for years over Australia’s public expression of national security concerns, including its ban on telecoms provider Huawei in 2018.

The election of Albanese’s Labor government last May allowed for a shift in those tensions, with Beijing gradually rolling back many of its trade controls since then – including on barley, timber, and coal – as the new Australian leadership dialed down the rhetoric.

Canberra announced Albanese’s trip late last month, shortly after the two countries reached a deal that could see the end of tariffs on wine – one of the most glaring sore points in that tranche of trade curbs, whose resolution the leader said would be worth about 1.2 billion Australian dollars ($773.6 million) to Australia.

During his meetings with Chinese officials, Albanese will likely push for lifting outstanding curbs, like those on lobster – and raise issues including China’s aggression in the South China Sea and its detention of Yang.

“When it comes to China what I say is we’ll cooperate where we can, we will disagree where we must, and we’ll engage in our national interest and I will always make representations on behalf of Australians,” Albanese told reporters on Wednesday, after confirming he was in touch with Yang’s family.

For Beijing, the Australian leader’s visit provides an opportunity to push for more Chinese access to Australia’s resources and renewable energy sectors, according to Elena Collinson, who manages research analysis at the University of Technology Sydney’s Australia-China Relations Institute.

Chinese leaders may also look for Albanese to support China’s entry to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a free trade pact between countries on both sides of the Pacific, she said.

For China, the visit coincides with its push to repair ties with other US-friendly economic partners, like those in Europe — part of bid to prevent them from falling too closely in step with America’s China policy.

“As tensions simmer with the US and its own economic position teeters on the precarious, it is in (China’s) interests to inject some stability into its relations with a resource-rich US ally,” Collinson said.

US relations loom

Albanese is heading to Beijing less than two weeks after he met with US President Joe Biden in Washington.

There, the two leaders expressed their shared concern over “China’s excessive maritime claims” in the South China Sea.

They also hailed the AUKUS security partnership between Australia, the US and the United Kingdom – which is supporting Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines, and the Quad, an informal grouping with Japan, India and the US.

As he aims to repair ties with China, Albanese will need to walk a line between these interests and China’s suspicions about the aims of these blocs, analysts say.

“Albanese can deliver the message, with regard to the Quad or AUKUS … Australia has this long history being part of (such) security arrangements – and (they) do not necessarily target China,” said Yuan in Sydney, who is also director of the China-Asia Security Program at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Albanese can also convey that what China does “could impact the direction of these arrangements,” he said, adding that Australia could provide an example to other middle powers with close ties to Washington about how to play a role in conveying messages between the US and China and navigating relationships with both powers.

Xi, meanwhile, is expected to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in San Fransisco later this month and meet with Biden, as the powers also seek to stabilize their fraught relations.

Easing of tensions with Australia could also help create a positive atmosphere ahead of those high-stakes talks.

And as China marks this new milestone with Australia, analysts say the Chinese leader and his officials may be taking note of the outcome of its economic campaign against the country.

“Beijing came to learn that the weaponization of trade did not force a close US ally to back down,” said Collinson. “And only served to intensify other countries’ suspicion and wariness of its motives.”

CNN’s Michelle Toh contributed reporting.