In a Tripoli hotel, Saleh Meshaashy shows pictures on his mobile phone of his father’s corpse; a massive bullet wound rendered his face unrecognizable.

Meshaashy is from a small town in Libya’s northwestern Nafusa Mountains, and many believe his tribe, the Meshaashiya, supported Muammar Qadhafi during the war.

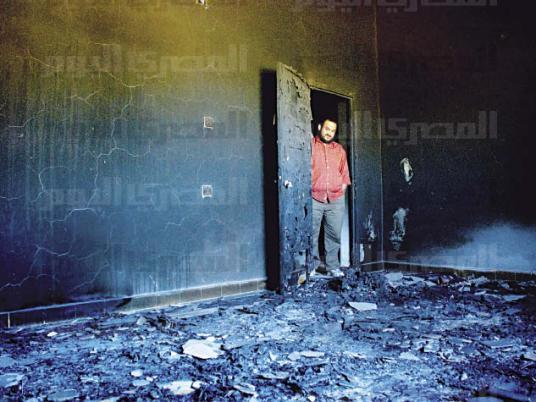

Meshaashy says he fled to Tripoli in 2011 to escape an inevitable showdown between approaching Qadhafi forces and opposition fighters from nearby Zintan. When the Zintanis arrived, they shot his father and razed their home.

He thinks the Zintanis were looking to exact revenge for a decades-long land dispute. During the 1970s, Qadhafi relocated the Meshaashiya from southern Libya to Zintan as part of his “divide and conquer” strategy to foment problems between different tribes. Recent graffiti outside Zintan reads, “Meshaashiya are the dogs of Qadhafi.”

Zintanis say their militia did not target civilians, and that the Meshaashiya are welcome to return if they can prove they own the land.

Khaled al-Zintani, the head of Zintan’s media center, says it was Qadhafi’s forces that set fire to Meshaashi homes to make foreign journalists think militias were the arsonists. Still, Zintani admits opposition fighters made mistakes.

“I don’t want to excuse them,” he says. “But you expect such things to happen in any war.”

The story of the Zintanis and the Meshaashiya illustrates the core transitional justice issues now facing Libya: the need for mechanisms to address injustices suffered under Qadhafi’s regime since the 1970s, and during the 2011 war. Without functioning reconciliation commissions or courts, the Zintanis and Meshaashiya have no forum to hash out historical grievances or investigate contemporary crimes on either side.

At stake in the transitional justice problem are the lives of tens of thousands of internally displaced persons and thousands of illegally held detainees. Transitional justice is also “inextricably linked to [Libya’s] stability, security and development,” David Tolbert, president of the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice, wrote.

Yet the current transitional government’s efforts on this front have fallen short of local needs and international standards. It remains to be seen whether Libya’s new government, elected last week, will successfully overhaul the country’s justice system.

New government, new prospects

On Saturday, Libyans went to the polls in the first national elections since 1965 to elect a 200-member General National Congress to replace the National Transitional Council, the self-appointed body that has governed Libya since October 2011. The newly elected congress will appoint a prime minister, who will then name a government.

The congress was originally meant to select a 60-member assembly to draft a constitution, seen as the cornerstone of a new justice system. However, two days before the election, the NTC issued an amendment stripping the congress of this responsibility.

The amendment stipulates that Libyans will choose members of the constitution-writing assembly in direct elections — a complicated twist on a body usually comprised of experts. Claudia Gazzini, senior Libya analyst at the International Crisis Group, says it will be difficult to find people willing to campaign for a seat in the assembly.

Most Libyans had not yet heard news of the change when they went to the polls. Gazzini reads the last-minute change as a concession to federalists in the east and south of the country who are agitating for autonomy from the central government. They have secured equal representation on the assembly for all three of Libya’s regions, despite massive population differences.

However, many eastern Libyans remained unsatisfied. Last week, federalists burned down election centers in the eastern cities of Ajdabiya, Benghazi and Tobruk.

While the constitution-writing process is important, it is not the only determinant of transitional justice. Gazzini prioritizes a “strong, well-functioning government.” The National Forces Alliance, a coalition of 58 parties that presented itself as a liberal counterweight to the Muslim Brotherhood, looks set to take most seats in the national congress.

While experts say Saturday’s elections were relatively free and fair, even in Qadhafi strongholds, it remains to be seen whether the head of the alliance, Mahmoud Jabril, can form a broad, authoritative coalition.

Little is known about how a potential coalition government would deal with transitional justice issues. Hanan Salah, a researcher with Human Rights Watch, says there had not been much discussion of justice issues during the campaign.

But with just a 14-day campaign window, most parties and individuals lacked detailed campaign platforms on any issue. Experts say the new congress must establish a national strategy for the justice system that lays out a robust legal framework to deal with criminal prosecutions, detainees and internally displaced persons.

Transitional justice laws

Gazzini argues that although the NTC had a “verbal commitment to transitional justice,” that commitment did not translate to a concrete prosecutorial system. During its tenure, the council passed just two laws dealing with transitional justice.

The first, the Transitional Justice Law, created a fact-finding and a reconciliation commission to help settle tribal differences and enable displaced people to return to their homes. Salah calls the law “weak.”

The second, Law 38, grants amnesty for “any acts made necessary by the 17 February revolution” — essentially granting immunity to those who may have committed serious crimes during the 2011 war.

Lawyers for Justice in Libya, a network of Libyan lawyers living in the diaspora, sent a letter in May to the NTC demanding Law 38’s repeal, as it “had terrifyingly familiar echoes of the Qadhafi era.” Yet the international community has largely ignored Law 38, indicating that many are willing to sacrifice justice to maintain Libya’s delicate political balance between militias and central authorities.

Criminal prosecutions

The International Criminal Court has warrants out for Saif al-Islam, Qadhafi’s second son who is currently detained in Zintan, and Abdullah al-Senussi, Qadhafi’s former spy chief, reportedly in custody in Mauritania. The NTC failed to bring either into their custody for trial.

The council was unable to convince the Zintani militia to hand over Saif al-Islam, as the latter worried that he could escape from the custody of weak central authorities. The government also failed to convince international jurists that it is able to try him domestically; a month ago, the court seemed poised to agree to trying him in Libya, but the detention of his ICC defense lawyer and three of her colleagues during a visit to Zintan derailed those negotiations.

The NTC’s efforts to get Senussi in custody also fell short. Although last week the Libyan press falsely reported that Prime Minister Abdel Rahim al-Keeb had managed to secure Senussi’s release, it was later discovered that he is still in Mauritanian custody. Some speculate the Mauritanians are loath to give up such a useful bargaining chip.

The transitional council was more successful in the beginning with a slew of domestic trials against high-level Qadhafi officials, including Abu Zaid Dorda, Libya’s former permanent representative to the United Nations and later head of intelligence services.

But a big problem, argues Gazzini, is that the council only dealt with high-level prosecutions. “At the top, it doesn’t require so much negotiation with the militias themselves,” she says. “Top members of the regime appear as a common enemy. The rank and file — they start becoming more problematic.”

Detainees and the displaced

When it comes to doling out politically costly justice, the most important issue facing the new congress will be dealing with Libya’s estimated 7,000 detainees, roughly 4,000 of whom are still being held by militias across the country. As noted in a Human Rights Watch report, “most of [the detainees] are Qadhafi security force members, former Qadhafi government officials, suspected Qadhafi loyalists, suspected foreign mercenaries or migrants from sub-Saharan Africa.”

The NTC has pressured militias to hand detainees over to central authorities, but militias are unlikely to do so if they expect the detainees will be released. The burden will fall to the congress to enforce laws stipulating that all detainees must be screened for evidence that they have committed crimes, and then either prosecuted or released. The NTC, argues Salah, had set unrealistic timetables and weak systems of accountability.

It will also be difficult for the new congress to deal with the thousands of internally displaced Libyans. Aside from the displaced Meshaashiya, around 30,000 to 35,000 people from Tawargha are living in temporary camps after being driven out by the Misrata militia for committing human rights violations for the Qadhafi regime.

Libyans hope the congress and the government it appoints will be a more legitimate and transparent body than the unelected NTC. At the very least, Libyans will have a body to hold accountable on issues of transitional justice.

Khaled, of the Zintan media center, insists that prospects for post-conflict reconciliation are good.

“We are all Libyan citizens. Let us solve our problems in the court, then come back as neighbors,” he says.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.