Immigrants sent a $38 billion (€31.1 billion) back home to Africa in 2017, according to a new World Bank briefing paper.

Nigeria accounts for the lion’s share of this with $21.9 billion, followed by Senegal with $2.2 billion and Ghana with $2.2 billion.

“The [African] diaspora … are making a lot of money and they are willing to share that money with the countries which they first came from,” said Africa commentator Ayo Johnson, who hails from Sierra Leone but is based in the UK. “Remittances are going back to their host countries in huge, huge volumes.”

Although the total amount of remittances sent worldwide hit record levels last year, the World Bank found this wasn’t the case in Africa. However, more money was sent to the continent in 2017 than in 2016 when migrants remitted $34 billion.

The real sums sent to Africa are assumed to be much higher. Not only is official data unreliable (or, at times, unavailable), remittances often flow through informal channels carried by trusted friends or bus drivers across borders instead of Western Union and MoneyGram.

An alternative source of income

Remittances have now become one of the most important external sources of finance for Africa.

“Remittances are a lifeblood,” said Nikki Kettles from Finmark Trust, a South African-based organization working to make financial services more accessible to the poor. She said it was families, especially to women and children, who benefited from remittances in southern Africa where her organization worked.

“People working in South Africa send money home, for example, to Zimbabwe, DR Congo and Malawi. People are using [the payments] to feed or educate, not for other reasons,” she said.

Numerous studies have found that remittances directly benefit the welfare of those receiving the money. In poorer regions and countries, such payments can often buffer the vagaries of poverty or instability by covering basic necessities such as food, school fees, rent and health care.

Remittances are also often used to start a business, build a house or buy a vehicle.

Less opportunity for corruption

One of the big benefits of remittances is that, unlike development aid, they flow directly into the pockets of the intended person.

“The strength of remittances is how they are dispersed,” said Mathieu Jacques, manager of the EU-funded ACP-EU Migration Action Programme (ACP stands for African, Caribbean and Pacific countries).

“There are project management cost savings in the way they reach the community,” he told DW. “And there is less opportunity for [payments] to be siphoned off or change direction.”

In some of Africa’s smaller or impoverished nations, remittances are literally keeping their economies afloat. According to the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances briefing,money sent by immigrants make up a significant share of gross domestic product in African countries such as Liberia (27 percent), The Gambia (21 percent) and Comoros (21 percent).

But even if remittances have the power to lift individual families out of poverty, their effect on a country’s economy as a whole is unclear. Some studies suggest remittances help fuel economic growth; other are less conclusive.

“One of the problems is that because [remittances] go into the community in a diversified fashion, there is no targeted investment,” said Jacques. “And without the targeted investment you can’t see incremental change from an economic perspective.”

Fees eat up nearly ten percent of payments

It costs more to send money to Africa – the world’s poorest region – than anywhere else in the world. This means expensive fees eat up a chunk of cash that could otherwise help the receiving families.

The average fees for transferring remittances to Africa was 9.4 percent in 2017, the World Bank found. This is a slight drop from 2016 (when it was 9.8 percent) but it’s still a far cry from the Sustainable Development Goal of slashing transaction costs to 3 percent by 2030.

“Countries, institutions, and development agencies must continue to chip away at high costs of remitting so that families receive more of the money,” said Dilip Ratha, lead author of the report, in a press release.

Companies like WorldRemit that offer cheaper transaction fees below 4 percent have limited resources compared to their much larger competitors to reach out to people in rural parts of the African continent.

It’s not just the cost of transferring money that is a stumbling block. Sending cash via money transfer companies also usually requires showing a passport or identity card which migrant workers might not have, or might not want to show because they lack work permits or visas.

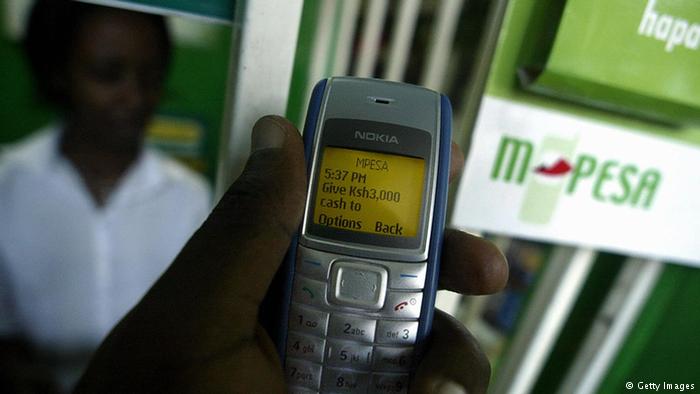

Many are putting their hopes in mobile money transfers as a way of cutting fees and making it easier for people to send and receive money across Africa’s borders. Some services are already offering cross-border mobile payments – although there are still issues such as compatibility and regulatory differences between countries that need to be ironed out.