When debate around a national salvation government (NSG) raged in the press two weeks ago, many opponents advanced various hostile arguments to the idea.

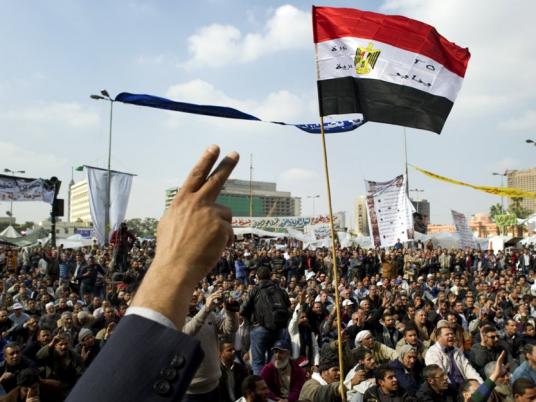

The call for an NSG came on the heels of six days of clashes that started on 19 November in Tahrir Square, during which police killed some 43 protesters while the military was silent.

In the wake of the violence, in Tahrir and across Egypt people demanded the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) immediately handover power to a civilian authority.

The SCAF turned a deaf ear to the call and unilaterally appointed Kamal al-Ganzouri prime minister after Essam Sharaf's resignation, without negotiations over what the cabinet’s executive authorities are under its interim rule, which is a contentious issue.

Some columnists were satisfied with labeling the cabinet formed by Ganzouri an NSG. They think it will make up for Sharaf's lax performance, particularly by re-establishing security, boosting the economy and responding to some of the most persistent demands of Tahrir. They trust the generals' good intentions to transfer power to civilians in due course.

In Al-Akhbar, columnist Taher Qabil criticized the call for the establishment of a NSG, arguing that it would only mean having three presidents instead of one "for a change."

In a piece in Al-Ahram entitled "A roadmap for salvation, as sketched by experts and politicians," “experts" gave various reasons for rejecting the idea of an NSG. Political analyst Hussein al-Libidi is reported to have described calls for the transfer of power to civilians as “thuggery on the part of satellite channels that receive foreign funding to incite people against the SCAF.” Another political analyst, Ahmad Shawqi, was reported to have depicted the situation as one in which the SCAF is held accountable for mistakes it has not made.

Refaat Said, head of the Tagammu Party, was quoted in another Al-Ahram piece as saying that even if the SCAF has inadvertently made some mistakes, its stepping would be equivalent to handing over the country to the Muslim Brotherhood. He added that forming a presidential council would "open the doors of hell," because it would be unconstitutional and because there would never be a consensus around its candidates. Fouad Badrawi, general secretary of the Wafd Party, was quoted as saying that the SCAF has no intention to stay in power and that there is no alternative to its rule. The piece ended with Norhan al-Sheikh, a professor of political science at Cairo University, saying she supports the SCAF staying in power for the lack of an alternative, and the majority of Egyptians share her view. She added that the Iraqi presidential council proved a failure and "we don't want the same disaster to happen in Egypt."

Some columnists went as far as to accuse Tahrir protesters of acting like dictators by imposing their views on the rest of the population. An article entitled "Athena's nobles and Tahrir's nobles" by Abdel Latif al-Mennawy in Al-Masry Al-Youm’s Arabic edition expressed surprise and dismay at the move taken by some protesters to survey the approval in the square for suggested NSG candidates. Mennawy exclaims: "What right have they — whoever they are — to decide on the behalf of Egyptians?" A similar stance was voiced by Salama Ahmad Salama in Al-Shorouk: "You can hardly go to bed with Ganzouri as prime minister and not wake up with another person, be it [Mohamed] ElBaradei, [Amr] Moussa, [Abdel Moneim] Abouel Fotouh or anyone you like, just because Tahrir said so."

Opponents of the idea of an NSG blame irresponsible, whimsical, unorganized young people with little understanding of politics or of what they want, and who — out of impatience or because they were maneuvered by certain forces — want to impose their so-called solution on the rest of Egypt. Mohamad al-Shamaa described Ganzouri as the most able man to form an NSG under the auspices of the SCAF, and definitely more able than the "Tahrir-elected Sharaf." Salama denounced Tahrir's rejection of Ganzouri, saying it is not based on his academic credentials but on "an unjustifiable insistence" on the transfer of power to a civilian government that was not implicated in Mubarak's regime, "however inconvenient such demands are in the current state of insecurity".

Less simplistic arguments criticize the idea of an NSG from a constitutional point of view, citing articles 56 and 57 of (the SCAF's) constitutional declaration, which stipulate the powers of the SCAF and the cabinet until presidential elections. They ask "Tahrir" to wait for the transition to follow its constitutional course as promised and planned by the SCAF. In Al-Masry Al-Youm on 28 November, Diaa Rashwan argued that any cabinet formed by the SCAF and its consultants from among the various political and youth groups will not be popularly elected and will therefore lack the legitimacy to exercise the powers that the SCAF currently exercises by law.

Behind the arguments against an NSG lie certain assumptions. One is that the democratic setbacks that have occurred in the 10 months since Mubarak's departure are incidental mistakes that the SCAF may have made either out of a lack of experience or because it inherited a country rife with corruption, a bad economy, and a divided opposition. Among those with this view are NSG opponents Tarek al Bishri, Fahmy Howeidy, and Diaa Rashwan — they trust the desired transfer of power will happen through parliamentary and presidential elections in due course.

Others however suggest institutional and legal alterations to facilitate cooperation between civil society and the SCAF and to correct the SCAF's biggest mistake: its exclusion of any civil partner. That's why Amr El Shobaki suggests only a partial transfer of power to an NSG; Sameh Ashour suggests that the SCAF should issue a law empowering the cabinet; Amr Hamzawi suggests “adding an exceptional layer” — i.e. a civilian entity — to the SCAF's decision-making process; and Moataz Bellah Abdel Fattah too demands that the SCAF should accept a civil partner rather than hand over power completely.