Every town has its story. Shalateen’s is on the precipice of a turning point.

Like each of us, towns are born and eventually die. Their life stories mimic those of people, except they exist over a longer time period. They have ups and downs, and reasons. And, like people, some are blessed from birth with the makings of success, while some are born with nothing. Some are still confused about what success means for them. Sometimes towns grow into cities; and sometimes, for reasons within or beyond their control, they wither away.

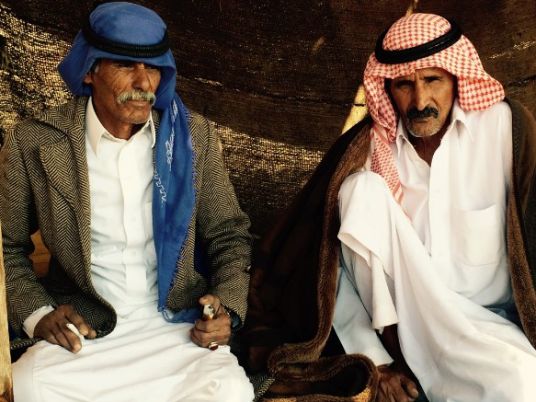

Shalateen, despite its being a relatively unknown town in an overlooked part of Egypt, has an interesting creation story. Its people hail from different parts of the world, including Sudan and the Arabian Peninsula, and they made the area their home a long time ago. While these people roamed the valleys and mountains for hundreds of years, only recently has there been a movement to settle by the seaside.

Some have chosen the outskirts, further into the desert and near the mountains, maintaining their “non-nationality” by belonging to the land and not the country that claims it.

Others have become naturalized Egyptian citizens. This move is in no small part helped by the work of the government, which only recently started to encourage permanent settlement of tribes in the area by providing basic services in addition to free water and electricity.

While Shalateen has been there for a relatively short period of time, its people have not, and the essence of their rich history and cultural heritage can still be experienced today.

The town itself, as part of the urban “civilized” world, is still a child and, like its people, unspoiled by the luxuries of technology and the extravagant choices available in big cities, it is still innocent and transparent.

But don’t be fooled: Children grow up fast. Shalateen, seemingly at the outer edge of Egypt, 1000 km south of the capital, is starting to become more demanding, as more and more people become aware that it exists. And as they learn of its existence, people are becoming more interested in Shalateen.

If you try to get to know someone or something, you start to uncover their past, like unwrapping the layers of an onion. We claim no knowledge of Shalateen’s onion core, but it doesn’t take long to get through the first layers. Unlike grown ups, who have been through a lot in life and are subsequently more opaque, children are easier to read in their innocence.

During its childhood, Shalateen’s importance lay in the fact that it’s a stopping point for traders coming from Sudan.

After childhood comes the worst phase of them all: the teen years. Shalateen is currently undergoing its own kind of adolescence. Like a hormonal teenager, Shalateen is ambivalent about the future, not sure where it wants to go. There are pressures from inside and out. There are conflicting interests and a sense of being lost.

And amid all that, there is a confusion about what Shalateen is today. The city is neither a port nor an old trading center, despite its popular market and the continuous heavy camel traffic–especially after rumors of the trade being moved to Halayeb scared off big traders, something more than a few locals referenced.

Our first window into Shalateen was an environment officer. He has lived in Shalateen for six years, and it seemed as though he, not unlike the locals, has started taking pride in simple things that distinguish Shalateen from other towns. One of those is the fact that it has remained–largely for political reasons–an unblemished spot of land.

Nearby towns are marred by signs of “civilization,” with four- or five-story concrete buildings for winter resort sites providing an example of what Shalateen could become, with its stretch of perfect beach and its impressive mountain range.

But the invasion of concrete monsters still seems to be the least of Shalateen’s worries.

It’s the cultural invasion that may alter the city most. The availability of satellite television and, in turn, the uncensored Western channels that it carries, are already making waves in what was otherwise a still cultural pool. It’s a first taste of what it’s like to have foreign ideas seep into the culture, and for some, the taste is sour. Some of the younger generations have already started to trickle into the town center, leaving behind the mountains and sheep herding in search of modern ways to make money and build homes.

Simply put, the advent of tourism brings in more money. But it also brings with it alcohol, drugs and free interaction with women, which are frowned upon within the tribes, even among their youngest members.

Herein lies the conflict. The worst part is that many seem to realize they have no say in where their town is heading. They know that the government, and the ruling National Democratic Party, have their own plans that will go through anyway. Hurghada and its closer neighbor Marsa Alam can testify to this.

Halayeb, a few hundred kilometers away, remains the main reason Shalateen is undiscovered. A diamond in the rough, it may remain so for as long as disputes between Egypt and Sudan over the Halayeb triangle continue. As well, the area around Shalateen is swarming with smuggling routes, if the accounts of locals are anything to go by.

Smuggling activity, which allegedly includes human trafficking, seems to be an obvious reason why it is difficult for tourists to obtain permits for a trek in the mountains or a safari ride. It also makes it dangerous for lone travelers, as a ranger residing there would have us understand, as visitors may become caught up in the middle of skirmishes between military and armed Bedouins.

Perhaps from all this trouble there is a blessing. As long as the politicking stands in the way, Shalateen may remain a teenager, beyond the grasp of greedy businessmen.

Then again, this could be a curse. Shalateen may remain an unheeded crossing point between important places, without ever becoming one itself.

Shalateen and Back Again travel series continues every Wednesday. Next week, Amr El Beleidy and Pakinam Amer describe what drew them to the southern border and what happened along the 1000km drive to get there.