January 1, 2012

At first, when it began nearly a year ago, many people thought it was just a copycat fad that would soon disappear. Inspired by the events of the Tunisian uprising, people–mainly young men–began to set themselves on fire.

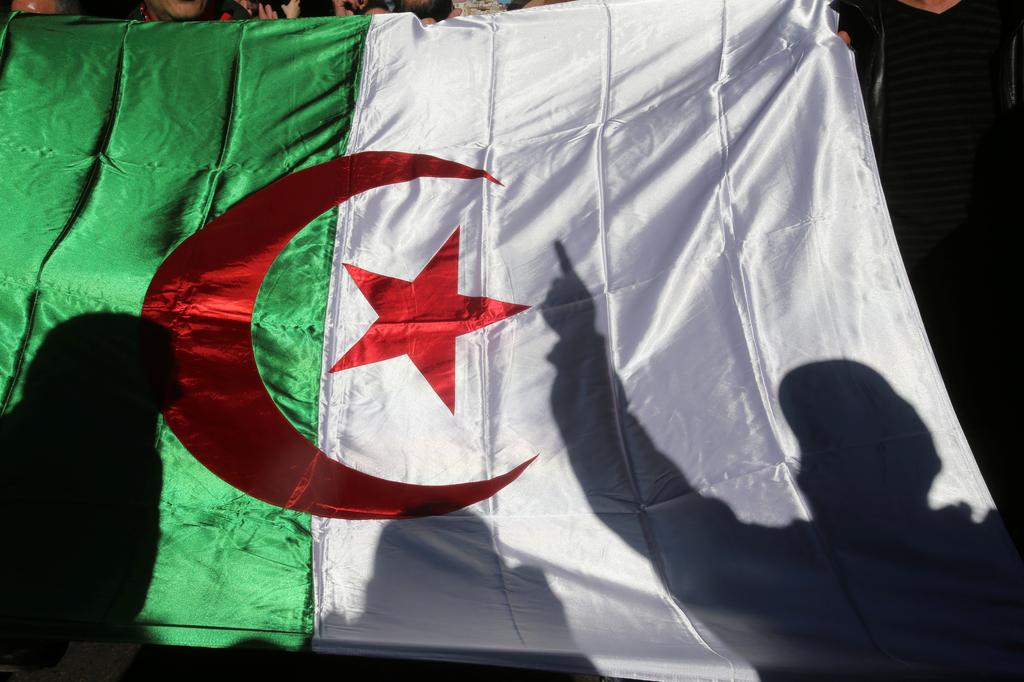

It began in Algiers, where riots had rocked the city for weeks and gangs of youth burned and ransacked government offices and luxury stores they could never afford to shop at. A few of these youth did not join, but expressed their anger and despair in another way. Protesting the hogra (contempt) the regime had towards them, they doused themselves with gasoline and lit a match. Sometimes, they would ask their friends to record them on their mobile phones.

Then, in Cairo, a snack shop owner from Ismailiya had set himself on fire in front of parliament, apparently protesting mistreatment at the hands of the authorities, which had refused to sell him subsidized bread. The next day, a retiree did the same and was barely stopped in time, while in Alexandria, a young man set him self alight on the roof of his building and died soon afterwards.

It was still the early days of the phenomenon, and most people, while concerned, thought it would quickly die down.

They were wrong.

Soon it began to take hold everywhere. A student in Aleppo who had failed his exams because he could not afford the books he needed set himself on fire in the middle of a busy square. After the secret police arrested his brothers and tortured them, his younger sister did the same.

In a village near Marrakesh, a farmer who no longer had enough water to irrigate his small plot of land (it was said that the water table had been drained by the new 18-hole golf course built by a royal adviser nearby) not only set himself alight, but also his wife and three children.

In Palestine, near one of the big Israeli settlements, a farmer walked through olive groves that had recently been cut down by armed settlers all the way to the gate of the settlement. Behind the gate, Haridim men watched as he screamed and did nothing to save him.

In Libya, the member of a tribe long marginalized by the Qadhafi regime traveled all the way from his home in the deep south to Tripoli, where he headed for the new building that hosted the fanfare of the fortieth anniversary of the 1969 revolution. Against a backdrop of a mural of the Libyan leader in African garb, he sat impossibly still as the flames engulfed him.

It continued here and there, gathering pace at an alarming rate. The most surprising was Egypt, where the reports of the incidents grew from a couple a week to, at its height, 12 in a single day. It might have simply been because it was the most populous country, and one of the youngest ones at that.

At first, opposition groups said it was the government’s fault, and ruling parties countered that it was the irresponsible rhetoric of anti-regime activists that had driven youth to radical acts. Soon enough, they stopped bickering and made joint appeals for young people to stop. Sheikhs issued fatwas to the effect that self-immolation was a sin, and priests delivered many impassioned sermons. On TV, evening talk show hosts tried to understand what was going on, blaming–all at the same time–governments, cultural imperialism and Israel. First Ladies launched national campaigns for the salvation of youth, and many vigils were held for the victims.

Security troops were deployed to gas stations to ensure that fuel would only be used in vehicles. Burning alcohol became a restricted commodity, sold only in pharmacies, as did paraffin and other combustible liquids. But it still didn’t stop.

In the West, pundits speculated about why this was happening. CNN ran a special report entitled: “Why Do They Hate Themselves?” Most said it was because Arab societies had reached an impasse, with young people demoralized that the change they yearned for seemed impossible. After what had happened in Tunisia, other Arab governments had beefed up security precautions, stabilized food prices, raised civil service salaries, and further restricted the activities of opposition groups.

On Fox News, some of the pundits said that it was a manifestation of a pathology peculiar to the Arab mind and added that a “cult of death” had spread throughout the region. They shut up after a member of the Tea Party set himself on fire in front of the White House wrapped in an American flag.

It all came to an end quite suddenly, mostly because of what became known as the Mothers’ Movement. Women who for years had been telling their sons to stay out of politics and out of trouble suddenly began to take to the streets. Across the region, hundreds of thousands of them took to the streets, laying siege to presidential palaces and parliaments, blocking traffic. The Arab world came to a standstill. Security forces were deployed but did not dare to act, not against frail old women who reminded them of their own mothers and sisters. Some of the world’s most feared and sophisticated systems of repression were simply neutralized, unable to act one way or the other.

I don’t need to delve into the political consequences. Entire governments were toppled. Dictators holding on to power for decades quietly stepped down. New constitutions were written, economic policies were abruptly changed and in every country new national projects were launched.

Overall, it is said that 1,432 people set themselves on fire. There were only 311 survivors, most of whom were disfigured for life. Many of them would go on to achieve great things.

[The above is a piece of fiction and not meant to offend or make light of the recent self-immolations. Deepest condolences to the families of the victims.]

Issandr El Amrani is a writer on Middle Eastern affairs. He blogs at www.arabist.net.