In the aftermath of the New Year's Eve church bombing in Alexandria that killed 22 and injured scores of others, some opposition figures fear the eruption of fresh violence in the absence of political liberalization and improved economic conditions.

“The solution lies in opening up the peaceful political sphere and granting people their basic rights to form associations and political parties,” said Bahey al-Din Hassan, director of the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies. “If the regime doesn't fix the problems caused by the last parliamentary election, we may see more people getting violent.”

There is a general belief that the current state of affairs–marked by political repression and economic stagnation–cannot be changed through peaceful means, according to Hussein Abdel Razek, leader of the opposition leftist Tagammu Party.

“People are facing dire socio-economic conditions,” Abdel Razek said. “Power and wealth are in the hands of the few while the many suffer from deteriorating living conditions. In the meantime, politics are monopolized by one party through electoral fraud–all this makes the situation more prone to violence.”

The Alexandria church bombing came on the heels of a controversial parliamentary poll marred by vote rigging, low turnouts and violence. Election monitors reported widespread violations, including ballot stuffing in favor of ruling party candidates. In the end, President Hosni Mubarak's National Democratic Party secured more than 90 percent of the seats in the assembly, while the opposition captured a mere three percent.

The Muslim Brotherhood opposition movement, meanwhile, which had held roughly one fifth of the previous assembly, failed to win a single seat.

What's more, the country remains riven by labor unrest due to steadily rising inflation coupled with inadequate per capita incomes. Since 2006, thousands of labor-related protests have been recorded, attesting to mounting popular disenchantment with the status quo.

Along with a marginalized political opposition and a discontented national workforce, the government also faces mounting displeasure on the part of the country's Coptic Christian minority. This has especially been the case since January 2010, when the killing of six Copts in a drive-by shooting on the eve of Coptic Christmas ignited widespread Coptic outrage. The incident aroused feelings of insecurity among many Copts, who accused the government of failing to protect them.

And in November, thousands of Copts clashed with police after authorities halted construction work on a church building in Giza. The disturbances alarmed many observers who posited that the Coptic lay community was becoming increasingly assertive about airing its grievances.

“For the first time, Copts took to the street instead of simply resorting to the church,” said Hassan. “And this trend has been exacerbated by the Alexandria church bombing.”

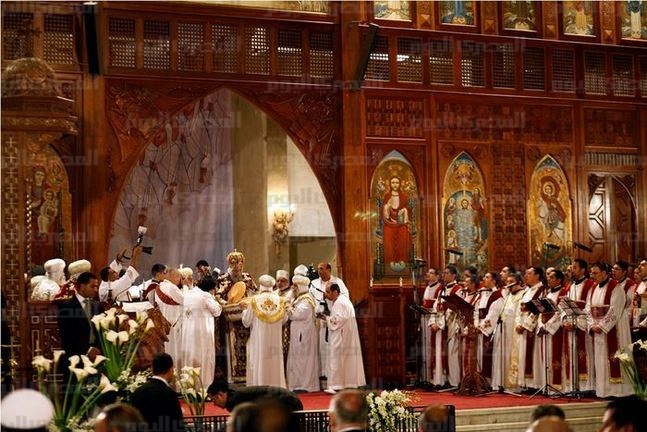

In the immediate wake of the attack, several Coptic protests erupted spontaneously in both Cairo and Alexandria. On Sunday night, thousands of Copts clashed with police outside Cairo's Coptic Cathedral in Abbasiya, reportedly damaging several passing cars in the process. Thirty five people were injured in the melee, including 15 Coptic protesters and 25 policemen.

Hassan expects the further radicalization of Egypt's Coptic minority, estimated to account for some ten percent of Egypt’s 80-million-strong population.

“The prevailing state of affairs is conducive to the rise of Coptic armed operations,” he said. “Channels of expression are closed to Christians more than any other group. Except for its recognition of Coptic Christmas as a national holiday, the state has continued to ignore longstanding Coptic grievances.”

For years, Copts have complained about restrictions on church building, the low number of Copts holding high government office, and what they describe as "Islamized discourse" in the local media and national educational curricula.

While the government has not yet identified the perpetrators of the Alexandria bombing, it has blamed the incident on “external forces” seeking to “destabilize” the country by jeopardizing “national unity." To diffuse mounting sectarian tension, ruling party officials have argued that the attack served to target "all Egyptians" and not solely Copts.

“The way the government is dealing with the issue is very dangerous,” said Amr Hamzawy of the US-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “If we keep blaming 'external forces' and reducing the reaction to just paying visits to the Coptic cathedral without fixing internal sectarian problems, the environment will remain conducive to sectarian violence coming from outside."

In the wake of the attacks, state-appointed Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmed al-Tayeb and Egypt’s Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa visited Coptic Pope Shenouda III to express their condolescenes and condemn the attacks. As they spoke to the press inside the Abbasiya cathedral, hundreds of Coptic protesters chanted anti-government slogans outside.

"Where is the Interior Minister when they are killing our brothers before our eyes?" they shouted. Some reportedly smashed storefronts and the windows of passing cars.

According to Hamzawy, the incident represented “clear evidence that the state is degenerating. Its symbolic leaders are not respected anymore, and its police are being beaten. This suggests that more violence could be in the offing.”