Editor’s Note: Arwa Damon, an award-winning former senior international correspondent for CNN, is president and co-founder of the nonprofit organization International Network for Aid, Relief and Assistance (INARA). The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

During past humanitarian missions in Gaza, aid workers like me entered through the Rafah border crossing with Egypt, where a sea of human desolation greeted us.

An overflow of tents spilled out of schools housing the displaced and blanketed the sidewalks. A handful of vehicles and donkey carts inched their way through a crush of human traffic. People were psychologically obliterated, alive but somehow dead.

Those harrowing Rafah scenes are all gone now, as I saw last month when I returned to Gaza on another humanitarian mission with my charity INARA after being away for two months. Israel’s incursion into Rafah has forcibly displaced more than a million people into the central part of the strip, where they claimed another miserable patch of land onto which they pitched their tents.

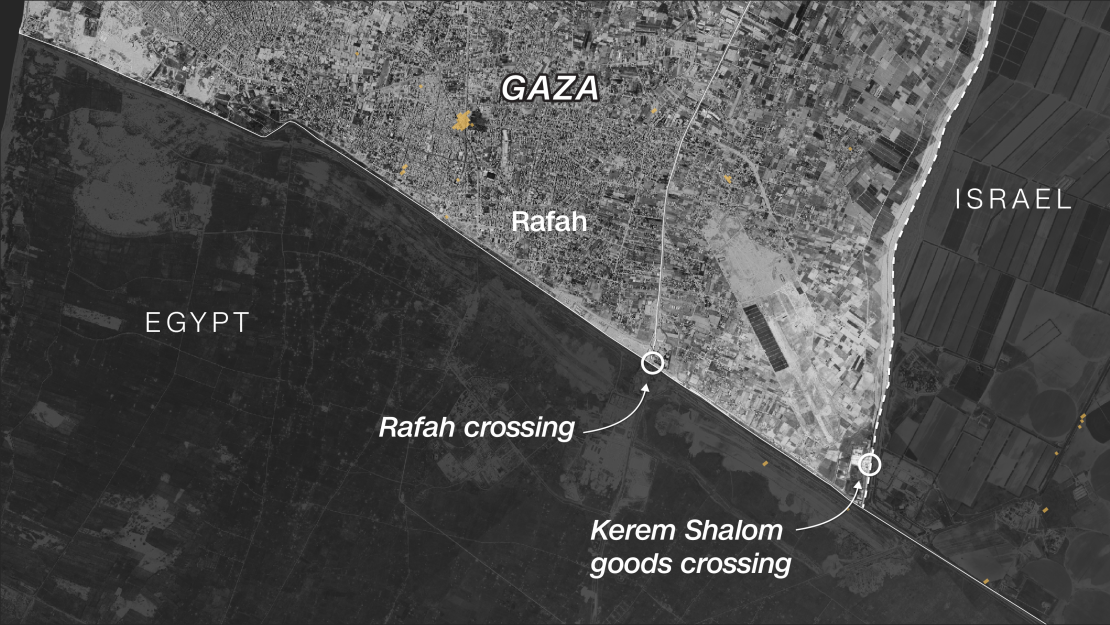

To make an unspeakably bad situation worse, the closure of the Rafah crossing has further handicapped humanitarian operations, shutting off the only route for medical evacuations and the only exit for Gazans. Aid workers like me now need to be picked up in an armored convoy at the southern border crossing with Israel, known as Kerem Shalom or Karam Abu Salem — “KS” for short.

Pain, fear, hopelessness, loss

Gaza is like nothing I have seen before. And I have been in enough war zones over the last 17 years to know that the explosive combination of pain, fear, anger, hopelessness and loss on the scale that Gaza and its people have suffered — coupled with growing lawlessness — will all but guarantee a deterioration into civil anarchy.

The constant desperation and fear have begun eating away at the moral codes that hold a society together. Without rule of law, without a peacekeeping force, without humanitarian aid, Gaza will combust and descend into civil chaos. And an unstable and uninhabitable Gaza only serves the apparent aims of Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his extreme right-wing government to avoid any good faith attempts at a lasting peace while Israelis encroach on more Palestinian land.

Through a walkie-talkie system, the voice from the lead vehicle in my convoy warns us of a “heavy presence of people” along our route and low visibility caused by dust, urging us to “keep the doors locked.” It’s an ominous sign of what may be yet to come in this already brutally battered land.

Increased looting, criminal activity and lawlessness within Gaza has people fearing what they call “the next war” when Israel’s offensive ends. The total security breakdown and lawlessness is potentially creating more of an opportunity for Hamas to re-emerge, even though no one I spoke to wants to see them back in power.

After 9 months of war, a craving for stability

Some Gazans, who have a strong craving for stability after nine months of hostilities, fear the mini-fiefdoms that are starting to form and the accompanying instability would create room for Hamas or its next iteration.

There is just one route that humanitarian organizations are permitted by Israel to use from the KS crossing to move deeper into Gaza. This route is used by both commercial and aid trucks, as well as convoys like the one I am in, transporting aid workers. On this road there is a stretch that we get a “green light” from Israel to travel on. This deserted stretch of road has become a haven for gangs and looters.

It looks like a scene from an apocalyptic zombie movie. The asphalt appears to have been chewed up and spat back out. What remains of buildings are little more than carcasses. Everything is rubble gray and burnt-out black. I crane my neck trying to take it all in, but it’s impossible.

Groups of men linger along the roadside, some carrying batons, a handful with machetes. They are waiting to ambush aid trucks, but they smile and wave at our far less tempting UN-marked jeeps. I watch two teens scrape the filthy ground collecting the remnants of an exploded bag of some sort of grain. This is effectively a “no man’s land” in a designated “red zone.” This is more organized, criminal and sinister than what you find when people who are merely hungry swarm an aid truck.

A flourishing black market in cigarettes

Some gangs are driven to looting for their own needs; others try to sell whatever they can get their hands on at market. But the savvier, more menacing groups are the various cigarette smuggling networks. Since October 7, cigarettes no longer enter Gaza as commercial cargo — no reason given, but hardly surprising, given there is a long and growing list of items arbitrarily restricted by Israel. On my trip to Gaza in April, an avid smoker I met joked, “They know that they can destroy us by cutting off our nicotine.”

Back then, the cost of a single cigarette was around $10. Now, it’s $17 to $25 depending on the brand. Smuggle just five cartons into a truck, and that’s about a hefty $20,000 payday. Aid trucks sometimes end up becoming unwitting mules for cigarette smugglers, one of the main reasons they are targeted.

To see this all firsthand is shocking, but hardly surprising. Earlier this year there was an attempt to use Gaza’s police force to secure aid and convoys, especially those departing from KS, but after they were repeatedly struck by Israel they withdrew. The desperation, lack of sufficient aid and lack of security have led to increased criminal activity, as Ambassador David Satterfield, the State Department special envoy for Middle East humanitarian issues, acknowledged as long ago as February in an interview with the Carnegie Endowment.

From the start, Israel has abdicated its responsibility to ensure the security of aid convoys and staff. The Israeli military agency for the Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, COGAT, is constantly posting updates about how many aid trucks are entering Gaza and blaming aid organizations for “failing at distribution.”

The sad irony is that aid organizations are failing at distribution. We simply cannot safely pick up aid from the border crossing without running a gauntlet of Israeli bombs dropping from the skies and looters and criminal gangs on the only routes we are permitted to use for pick up. Israel does not permit us to use alternative routes. We don’t even have permission to bring in equipment needed to fix the trucks that are barely hobbling along. The crippled process complicates an already challenging security situation.

It feels like the edge of an expertly orchestrated anarchy, part of a vicious strategy to bring Gaza to its knees. As desperation increases, more people are forcibly displaced yet again, and resources start to flatline.

Laying the groundwork for the ‘war within’

We drive past a vast expanse of desolation: barely standing shells of what used to be people’s homes. I watch children sifting through the rubble. My eye catches the bright sparkle of a green sequined bit of cloth, then a purple one. Was that a dress shop? The remnants of someone’s closet? Children run past open sewage with no shoes on, others carry water jugs almost as heavy as they are. In the distance you can hear sporadic bursts of gunfire in neighborhoods far from any sort of frontline.

“Don’t worry, it’s just tribal feuds, but we better get inside,” says one of the men setting up solar panels for a shelter that INARA is supporting, ushering us off the rooftop one evening. Our eyes lock and I can see his fear. It’s a fear I have seen and heard expressed numerous times this trip into Gaza. A fear of “the war after the war.” Some believe it has started already. “We are scared of what is coming next,” he says, shrugging.

Gaza is no stranger to the tribal family and gang dynamic. As one Gazan friend explained: “Hamas kept all the family tribal clashes, the criminal gangs under control. It was one of the reasons they were initially so popular,” she told me. “That is all being recreated right now in the lawlessness, the smugglers, the mafias that are emerging.”

“I feel like it’s all poised to turn into Baghdad at its worst, not split along sectarian lines obviously, but a patchwork of mini fiefdoms each controlled by a mafia or family,” I say, based on my travel in other war zones. “Yes. That’s why we need an international peacekeeping force,” she responds.

She tells me: “We don’t want Hamas back; we definitely don’t want Hamas back. Right now, there is barely any support for Hamas. But if, after this, this chaos gets worse, then people will start to crave any stabilizing force, and support can flip back towards Hamas.”

Driving out of Gaza 10 days after my arrival, I see a cluster of burning tires. A couple of groups have tree trunks, metal cabinets — any form of debris ready to chuck across the road to force a truck to stop. The no man’s land is even more desolate. We drive past the truck drivers waiting to load cargo. “What brave men,” I think to myself. “They are risking airstrikes and ambushes.”

In the days since I’ve left, KS has all but shut down. I remember the words of a Gazan colleague working for another organization. “This war is designed to destroy us and ensure that we destroy ourselves,” he told me. “Everyone is just trading in our blood.”