(CNN) — Early on Christmas Day in the central Gazan city of Deir al-Balah, Motaz Azaiza shared a terrifying update on X.

A quadcopter was flying low above the door of his house, he said, and he feared he was about to be targeted in an Israeli airstrike. As a highly visible Palestinian online who had received threats before, Azaiza believed he had reason to be afraid.

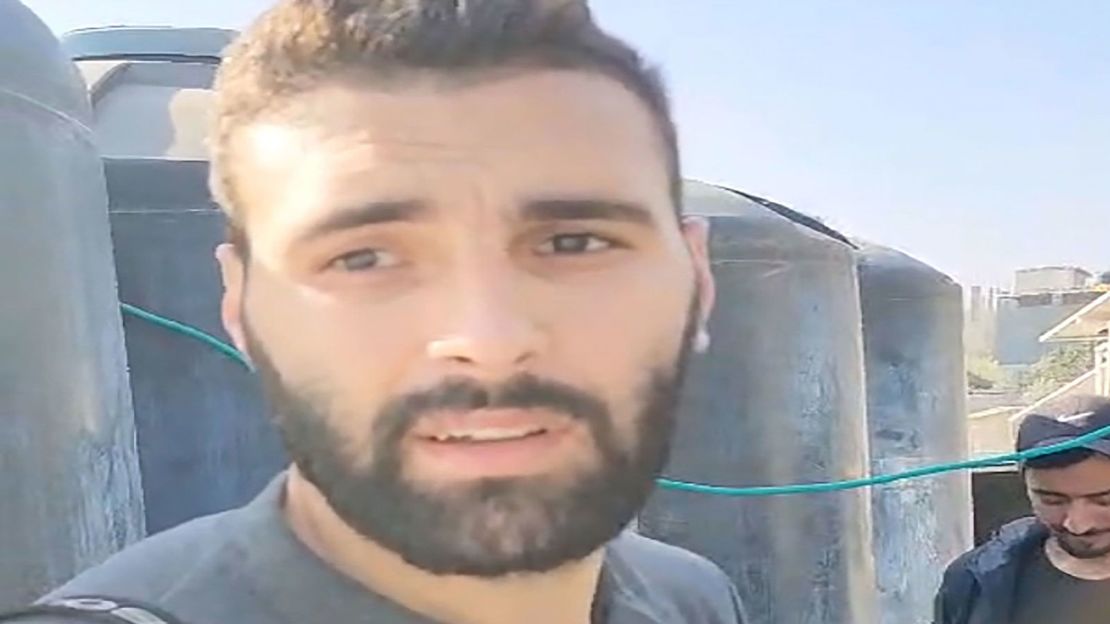

Hundreds of people flooded the replies with concern for the 24-year-old Palestinian photojournalist, who has been documenting Israel’s military assault on Gaza on social media since Hamas’ attack on Israel on October 7.

“I’m so scared for Motaz,” the replies read.

“I hope Motaz is okay.”

“Pray for Motaz.”

Noor, a medical student in California who asked to go by her first name for safety reasons, was one of the people worrying. For months, she’s been following Azaiza’s dispatches from Gaza, broadcast to his millions of followers: images of his once vibrant neighborhood transformed into a gray wasteland, raw glimpses of carnage in the ashes, and reflections on his own feelings of rage and exhaustion.

Noor refers to Azaiza with the familiarity of his first name. She gets notifications on her phone each time he posts, and worries when too much time passes.

“For so many of us, it almost feels like he’s a brother. He’s a friend, and we’re seeing him suffer in real time,” she told CNN.

Noor isn’t Palestinian and has never been to Gaza. What’s happening there still hits close to home. Her family is Iraqi, and she grew up against the backdrop of the Iraq War. When Azaiza said he feared being killed for his work, Noor found herself feeling scared and anxious for a virtual stranger halfway around the world.

“Their journalism isn’t just journalism. It’s a diary,” Noor said of the Gazans posting on social media. “They’re showing us their lives. They’re telling us, ‘Hey, I couldn’t shower for a week.’ ‘Hey, I barely had some of this to eat today.’”

After hours with no information following that fear of an airstrike, Azaiza finally posted again. A targeted attack on his house hadn’t materialized, but there was bad news elsewhere: a refugee camp was hit in an Israeli attack.

Still, his posts signaled he was alive, and Noor could breathe a sad sigh of relief.

Palestinians on social media are a window into the war

Like millions of others around the world, Noor is witnessing the war in Gaza through the eyes of Palestinians who are sharing their daily realities on social media. Through their posts on Instagram, X and other platforms, these citizen journalists are putting a face to the conflict.

In return, their followers are developing strong emotional connections with them.

Leyla Hamed, a sports journalist in London, said the first thing she does when she wakes up is open Instagram to visit the profiles of Palestinians she follows and watch their stories one by one. As a journalist herself, she sees them as colleagues and feels a responsibility to bear witness.

“I feel so much empathy for them that I sometimes feel scared to open their profiles, just thinking something bad has happened to them,” she said.

Kanwal Ahmed, a filmmaker and storyteller in Toronto, has a similar routine.

“They’ve become family to the entire world,” she said. “If (creator Bisan Owda) hasn’t posted for 12 hours, there are hundreds of tweets: ‘Where’s Bisan?’ ‘Does anybody know where Bisan is?’ ‘Is she okay?’ If (Azaiza) has posted a picture where you can tell that he’s looking extremely depressed or he’s lost weight, there’s people discussing that.”

These images and accounts from Palestinians offer an instantaneous view that some young people feel like they haven’t gotten from traditional media outlets, Ahmed said. Young Palestinians like Azaiza, content creator Bisan Owda and freelance journalist Hind Khoudary haven’t just been on the ground since the beginning. They are reporting from their homes and their communities, often persisting through extended communications blackouts like the current one that began January 12.

Through raw, selfie-style videos chronicling the ever-present threat of explosions or the everyday indignities of displacement, they’re giving outsiders an intimate look at the human costs of war from the perspective of people who live there. Many of the images they share are so graphic that Instagram obscures them with “sensitive content” warnings.

“Everyone’s getting a chance to tell their own stories,” Ahmed said. “People can tell for themselves … And it’s very hard to look away when you’re seeing somebody sitting in a pile of rubble, or if you’re seeing a five-year-old girl crying next to her father’s dead body.”

Seeing the war directly through these channels changes how people understand it, said Zaina Arafat, a Palestinian American author in Brooklyn who has written about witnessing the assault on Gaza through Instagram.

“The constancy of these images and the way that we watch them through our phones very much in private allows for a more direct and forceful impact,” she said. “It’s this very immediate connection between journalist and viewer, which I do think heightens the response.”

They are changing the way the world sees war

Israel began its relentless bombardment and ground assault in Gaza after Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, killing more than 1,200 and taking more than 200 hostages, according to Israeli authorities.

Israel says its offensive is aimed at wiping out Hamas, a militant group that the US, European Union and others consider a terrorist organization. But the conflict has also created a humanitarian crisis — one that people around the world are able to see up close.

Direct accounts from Palestinians are one of the most reliable ways for people to understand the devastation in Gaza, where about one in every 100 people has been killed and more than one in 40 have been wounded since the war began, according to the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Ramallah, which draws its statistics from hospitals in Hamas-controlled Gaza. Israel’s military denies accusations that it deliberately targets civilians.

“This is as close as you can get to factual and minute-by-minute reporting on the atrocities on the ground,” said Marwa Fatafta, an analyst and researcher who leads Middle East and North Africa policy and advocacy work for the digital rights organization Access Now.

Independent journalism out of Gaza is scant. With notable exceptions, among them international news agencies such as Reuters and Agence France-Presse, most news organizations have been unable to cover the war in Gaza with their own correspondents. Israel, along with Egypt, has largely blocked international journalists from the territory on the premise that it cannot guarantee their safety. The few foreign journalists who have been allowed to enter have primarily embedded with the Israel Defense Forces and may have had to submit their footage to the military for security review.

In December, two months into the war and after weeks of trying, CNN’s Clarissa Ward and her team finally gained access into southern Gaza without the IDF. Their trip was facilitated by the Emirati government, which runs a hospital inside Gaza. Still, such independent reports remain rare.

Eyewitness accounts on social media are critical in understanding global conflicts, including past flare-ups between Israelis and Palestinians. In 2021, Palestinian poet and writer Mohammed el-Kurd rose to social media prominence for his activism around a series of forced eviction cases in his Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem.

What’s different this time, according to Fatafta, is how many more people are paying attention.

“What we see now is a continuation of what happened in 2021, but of course, on a massive scale, because also what’s happening in Gaza is unprecedented,” she said.

Before October 2023, Azaiza had about 25,000 Instagram followers, according to the social media analytics firm Social Blade. That number has since grown to more than 18 million. Bisan Owda has 3.8 million followers, and Hind Khoudary recently surpassed one million.

The reports show how much violence has affected their lives

Plestia Alaqad said she wanted to tell stories about the beauty of Gaza before the events of October 7 turned her into a de facto war reporter.

After one of her videos capturing a blast going off near her building went viral, she said she felt a duty to continue. Like many Gazans on social media, she posted in fluent English, allowing her photos and videos on Instagram to reach a global audience that now numbers 4.7 million people.

“As a Palestinian living in Gaza, you don’t have a choice but to be a war journalist,” Alaqad, 22, said in an interview with CNN. “Overnight, your life changes. Overnight, a war happens and you don’t have an option. You found yourself reporting to the world what’s happening, whether you like it or not.”

Alaqad has been on both sides of this dynamic, first as a citizen journalist and now as a viewer. Through October and much of November of 2023, she was reporting daily on what was happening on the ground in Gaza, with her followers hanging on to every update.

As overwhelming as it felt at times to have so many people relying on her for updates, Alaqad said she wanted viewers to feel connected. She didn’t want people to learn from TV about some new tragedy in Gaza and just move on with their day.

She wanted viewers to see Palestinians as someone’s child, friend or neighbor, with lives and dreams of their own.

“It’s not about me as Plestia,” she said. “It’s about me as a Palestinian. I’d like people to know about Palestine, to see Gaza through my eyes.”

In November, she made the difficult decision to leave Gaza with her family after her uncle in Australia secured emergency visas for them. Now watching from afar in Melbourne, she’s the one refreshing her social media feeds and anxiously texting relatives, friends and colleagues to make sure they’re safe.

The everyday details are just as moving as the violence

Viewers who scroll back far enough through these Gazans’ social media posts are hit with sobering reminders of a life before the war. Motaz Azaiza was still documenting flare-ups in the ongoing conflict before the events of October, but he also spent time near the sea photographing children playing and shared a selfie celebrating his graduation from university. Plestia Alaqad filmed a tour of Gaza’s Old City, did a photoshoot in a motorcycle helmet and posed for pictures with dogs.

“They would go to restaurants. They would go to the beach. They would watch their favorite films. They would take care of the gardens. They have a life just like me and you,” said Leyla Hamed, the sports journalist.

Others can still see themselves in parts of these people’s lives, even as they are under siege. Last month, Owda shared that she had to chop off her signature brown curls because she no longer had clean water or products to care for her hair properly.

It might seem trivial to mourn the loss of hair in such a situation, but it was an intimate detail people could identify with, said Syed Faizan Raza, a design researcher in Islamabad.

“It goes back to those moments of relatability and how you are familiar with these people. Everyone knows these people by name and they’re following them quite diligently,” he said.

The connections are virtual, but the danger is very real

The work of these photographers, storytellers and citizen journalists is dangerous.

At least 82 journalists and media workers have been killed while covering the war as of January 16, 75 of them Palestinian, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists. Reporters in the region also face assaults, arrests and threats, in addition to communications blackouts.

The landscape is so dire that some have decided to cease their efforts. On January 10, blogger Ismail al Dahdouh announced to his 1.2 million Instagram followers that he would no longer be documenting the war in order to seek safety with his family.

Other Palestinian creators continue to record with relentless dedication. Sometimes, they express despair over whether anyone is listening, or whether their reporting makes a difference.

One day in early December, their exhaustion was especially apparent.

“I no longer have any hope of survival like I had at the beginning of this genocide, and I am certain that I will die in the next few weeks or maybe days,” Owda wrote in a December 2 Instagram post. (Israel has denied allegations of genocide in Gaza, claiming its actions in the region are in “self-defense” and that it is targeting Hamas rather than civilians.)

“The phase of risking my life to show the world what’s happening is now over. A new phase has begun — the phase to survive,” Motaz Azaiza wrote in Arabic in an Instagram post that same day.

Despite the pain, people watch to learn and bear witness

Even as people flock to learn from and support these Palestinians on social media, Noor says the exchange is overshadowed by feelings of powerlessness.

“For (Azaiza, the photojournalist), it’s almost like he’s a representative of his people,” Noor said. “By extension, your care isn’t just for him. Your care is for everyone because he is showcasing what his people are suffering.”

Still, Noor and other followers hope that their advocacy for Palestinian stories can keep public attention on the crisis in Gaza and put pressure on elected officials to bring about an end to the fighting.

In the US, people are encouraging each other to contact their representatives in Congress and demand they support a lasting ceasefire. Protests, demonstrations and public gatherings in support of Palestinians have grown in size since the start of the war, according to data from scholars and researchers with the Crowd Counting Consortium. A December 2023 Quinnipiac University poll found that US voter support for sending military aid to Israel had dropped. Israel is facing mounting international pressure to agree to a ceasefire, or at least moderate its offensive in Gaza. And in what it describes as a new phase of the conflict, the Israeli military said it has started to withdraw some troops.

It’s difficult to attribute these events to any one factor, and Fatafta cautions against drawing too straight a line between social media and changing opinions on the war. There is a rich history of solidarity with Palestine in the Arab world and beyond, and Fatafta said the massive social media followings of Palestinians like Azaiza partly reflect that.

“And it’s only growing, because also the events on the ground are beyond atrocious, and they do merit a global reaction,” Fatafta said.

“If there wasn’t, I would be scared to live in this world.”

Constantly checking Instagram to make sure Azaiza and other Palestinians documenting the war are still alive feels dystopian, Noor said. She’s had to take a break at times because the horrors she was seeing through her phone were affecting her ability to function. But she knows those in Gaza don’t have that luxury, so she never looks away for long.

“The least that I can do, or anybody can do, is to bear witness,” she said.