The Nobel Prize committee announced the prestigious honor, seen as the pinnacle of scientific achievement, in Sweden on Monday.

It praised the scientists’ “groundbreaking findings,” which the committee said “fundamentally changed our understanding of how mRNA interacts with our immune system.”

Karikó and Weissman published their results in a 2005 paper that received little attention at the time, it said, but later laid the foundation for critically important developments that served humanity during the Covid pandemic.

“The laureates contributed to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times,” the committee added in a statement.

Rickard Sandberg, a member of the Nobel Prize in medicine committee, said “mRNA vaccines together with other Covid-19 vaccines have been administered over 13 billion times. Together they have saved millions of lives, prevented severe Covid-19, reduced the overall disease burden and enabled societies to open up again.”

Karikó, a Hungarian-American biochemist, and Weissman, an American physician, are both professors at the University of Pennsylvania. Their work became the foundation for Pfizer and its German-based partner BioNTech, as well as Moderna, to use a new approach to produce vaccines that use messenger RNA or mRNA.

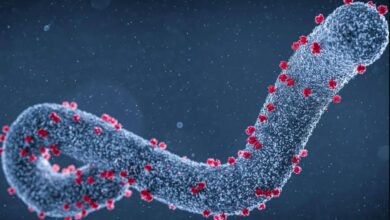

Messenger RNA is a single strand of the genetic code that cells can “read” and use to make a protein. In the case of this vaccine, the mRNA instructs cells in the body to make the particular piece of the virus’s spike protein. Then the immune system sees it, recognizes it as foreign and is prepared to attack when actual infection occurs.

This design was chosen for a pandemic vaccine because it’s one that lends itself to quick turnaround. All that is needed is the genetic sequence of the virus causing the pandemic. Vaccine makers don’t even need the virus itself – just the sequence.

“The impressive flexibility and speed with which mRNA vaccines can be developed pave the way for using the new platform also for vaccines against other infectious diseases,” the Nobel committee said, adding that the technology “may also be used to deliver therapeutic proteins and treat some cancer types.”

J. Larry Jameson, executive vice president of UPenn’s School of Medicine, praised the scientists’ work which “changed the world.”

“During the biggest public health crisis of our lifetimes, vaccine developers relied upon the discoveries by Dr. Weissman and Dr. Karikó, which saved innumerable lives and paved a path out of the pandemic,” Jameson said in a statement. “More than 15 years after their visionary laboratory partnership, Kati and Drew have made an everlasting imprint on medicine.”

The Nobel Prize announcements began in Sweden Monday and will continue throughout this week and into next, with awards in physics, chemistry, literature and economics set to be announced in the coming days. The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced in Norway on Friday.

The road to the Nobel

Karikó, 68, began her career in her native Hungary in the 1970s, when mRNA research was new. She, her husband and young daughter left for the United States after she received an invitation from Temple University in Philadelphia. They sold their car, Karikó told The Guardian, and stuffed the money – an equivalent of about $1,200 – in their daughter’s teddy bear for safekeeping.

“We had just moved into our new apartment, our daughter was 2 years old, everything was so good, we were happy,” Karikó told the Hungarian news site G7 of her family’s departure. “But we had to go.”

She continued her research at Temple, before joining the UPenn’s School of Medicine. But by then, the initial excitement surrounding mRNA research had started to fizz out. Hope turned to skepticism: Karikó’s idea that it could be used to fight disease was deemed too radical – and too financially risky to fund.

She applied to grant after grant, but a string of rejections meant that in 1995, she was demoted from her position at UPenn. She was also diagnosed with cancer at the same time.

“It was difficult because people did not believe that messenger RNA can be a therapy,” Karikó told CNN, in an interview during the pandemic in December 2020.

But she stuck at it. “Together with my colleague, Drew Weissman, at the University of Pennsylvania, we developed this method where we changed one component in the RNA which made it less immunogenic. It is possible to use it for different kinds of therapies, Karikó said.

Weissman told CNN that their technology is much more efficient than traditional methods of producing vaccines.

They did not even need a sample of the virus itself. “When the Chinese released the sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we started the process of making RNA the next day. A couple weeks later, we were injecting animals with the vaccine,” he said.

At the time Karikó said she was not at all surprised by the successful results of the trials conducted by Pfizer and Moderna. “I expected that it would work, because we already had enough experiments,” she said.

She celebrated the successful trial results with a bag of Goobers, chocolate-covered peanuts, her favorite candy. “I’m not an exuberant person,” Karikó told CNN.

CNN’s Maggie Fox, Leah Asmelash and AJ Willingham contributed to this report.