In schools across the country, service in the armed forces is being glorified, “voluntary companies” of teenagers are being formed and the national curriculum is being changed to emphasize defense of the motherland.

In short, Russia’s children are being prepared for war.

The militarization of Russia’s public schools has intensified since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, driven not by a spontaneous surge of patriotic feeling, but by the government in Moscow.

The investment is huge. Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov said recently that there are now about 10,000 so-called “military-patriotic” clubs in Russian schools and colleges, and a quarter-of-a-million people take part in their work.

These clubs are part of a multi-pronged effort that includes a radical overhaul of the school curriculum. There are mandatory classes on military-patriotic values; updated history books accentuate Russian military triumphs.

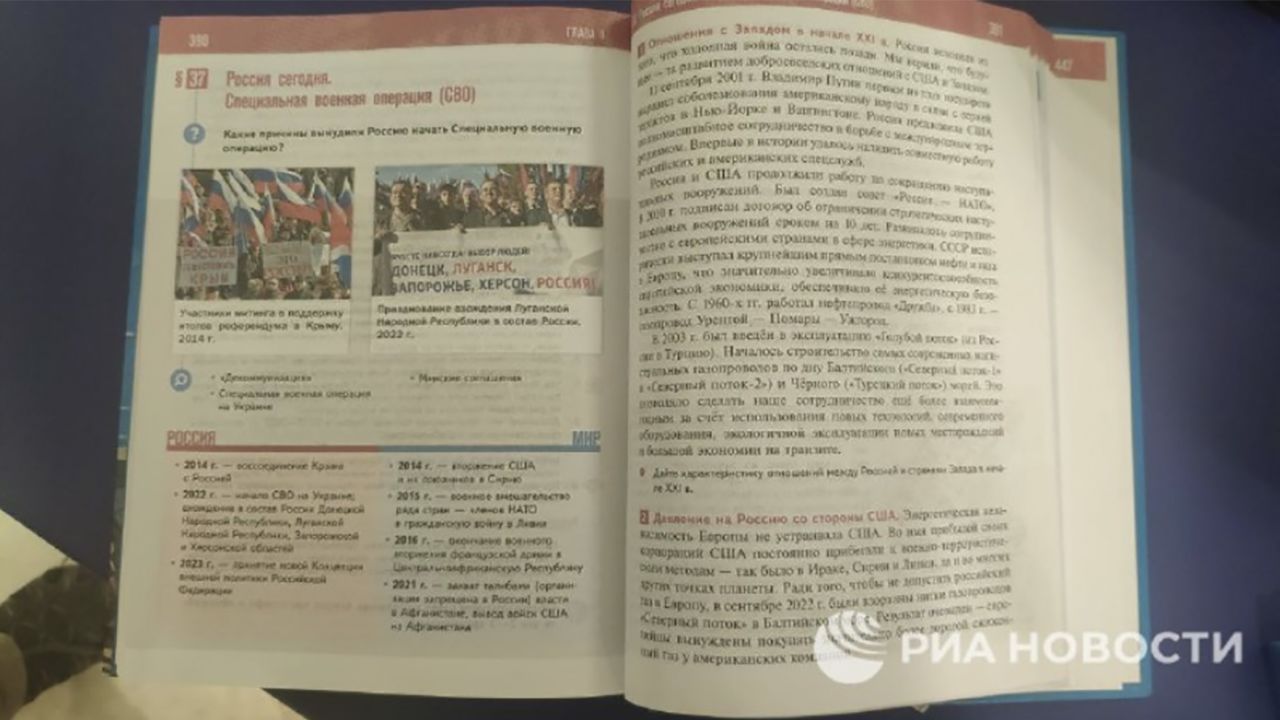

Changing textbooks

In August, President Vladimir Putin signed a law introducing a new mandatory course in schools: “Fundamentals of Security and Defense of the Motherland.”

The Education Ministry subsequently promoted courses as part of this initiative to include excursions to military units, “military-sports games, meetings with military personnel and veterans,” and classes on drones.

High-school students would also be taught to use live ammunition “under the guidance of experienced military unit officers or instructors exclusively at the firing line,” according to the ministry.

The program, which is being tested this year and will be introduced in 2024, is designed to instil in the students “an understanding and acceptance of the aesthetics of military uniforms, military rituals and combat traditions,” according to an Education Ministry document uncovered by the Russian independent media outlet Important Stories.

Modern history is being rewritten too. The standard textbook, ‘History of Russia,’ now has the Crimea Bridge on its cover and a new chapter devoted to the recent history of Ukraine. There are sections entitled “Falsification of history,” “Revival of Nazism,” “Ukrainian neo-Nazism,” and “Russia is a country of heroes.”

Putin has repeatedly falsely framed the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a “special mission” to protect Russian speakers from genocide at the hands of “neo-Nazis.”

A new chapter falsely claims that Ukraine “openly declared its desire to acquire nuclear weapons,” and “unprecedented sanctions have been introduced against Russia, since the West is trying in every way to bring down the Russian economy.”

The book appears designed to stoke a sense of historical grievance among Russian children and lay out an existential battle for the nation’s survival, a common theme in the state media pumped daily into living rooms across the country.

President Putin has personally led the campaign to inject patriotism into Russia’s schools. At an event at the Kremlin this month, he told a group of children about a letter that his grandfather had sent to his father, who was fighting the Nazis during the World War II.

“Beat the scum!” he had told him, according to Putin’s account.

Putin went on: “I realised why we won the Great Patriotic War. People with such an attitude simply cannot be defeated. We were absolutely invincible, just as we are now.”

Children taught to assemble guns

An extensive survey by CNN of local and social media in Russia found that children as young as seven or eight are receiving basic military training.

In July, for example, children in Belgorod gave themselves call-signs – one adopted “Sledgehammer” – and took part in exercises that included the use of automatic weapons, assembling a machine gun and getting through an obstacle course.

Belgorod’s Governor Vyacheslav Gladkov suggested conducting exercises with schoolchildren and pre-schoolers regularly.

In Krasnodar in May, dozens of children who looked no more than seven or eight years old marched in army and navy uniforms, some clutching imitation automatic weapons, as they passed dignitaries on a podium.

In a parade held in the city of Vologda, a small child saluted and told an official: “Сomrade parade commander! The parade is ready. I am Commander Uliana Shumelova.”

Similar scenes have played out from Sakhalin in Russia’s Far East to Yeysk on the Sea of Azov. Some of the children look excited, some bewildered. In Yeysk, a pre-schooler led the march of the border guards, as his peers chanted: “One, two, three. Left, left, left!”

Most of the children in these parades are in one sort of military uniform or another, trying to march in step without much success. Frequently they carry pictures of Russian military heroes.

The symbolism of what the Kremlin calls the “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine is also celebrated. In the city of Astrakhan, nursery children wore uniforms and had toy vehicles emblazoned with the letter Z, a propagandist symbol used to show support for the Ukraine war.

The Ministry of Defense has scaled up its outreach to schools with a well-publicized Christmas Tree of Wishes’ program, similar to the Make-A-Wish Foundation, in which the minister himself, Sergei Shoigu, has been active.

Shoigu invited a 9-year old girl called Daria from Udmurt to the Victory Day parade in Moscow in May. Other children visited military helicopters and the Air Defense museum.

Next generation being prepared for army service

Russia’s children are also expected to contribute to the war effort in practical ways. The governing United Russia party launched a program in Vladivostok in which school kids sew pants and caps for soldiers (in the pattern of the party.)

In Vladimir, children have been sewing balaclavas for the military in labor lessons, as part of a campaign called “We sew for our men.”

Students at a technical school in Voronezh were tasked with making mobile stoves and trench candles for the Russian military. Disabled teenage girls in Ussuriysk were drafted into sewing “Friend or foe” headbands and bandages for the Northern Military District. And in Buryatia in the Russian Far East, orphans sewed ‘good luck’ amulets for soldiers fighting in Ukraine.

There are also letter-writing campaigns. “Five-year-old boys from kindergarten answer with confidence,” a local news outlet in Chita trumpeted. “Before sealing the triangular envelope, they carefully colored the image of the fighter.”

All these activities are publicized in regional media as part of a broader effort to rally patriotic spirit in support of the Ukraine campaign.

Teenagers are also encouraged to compete in what are called Youth Military Sports Games.

The district final in the Orenburg region has just finished. 180 athletes from 14 teams – including the illegally annexed regions of Ukraine – took part in a variety of competitions: grenade throwing, drill training, overcoming an obstacle course and assembling a Kalashnikov assault rifle, store equipment and a military history quiz.

The goal, according to the Defense Ministry, is to “cultivate a sense of mutual assistance and comradely support, high moral and psychological qualities, as well as prepare the younger generation for service in the Armed Forces Russian Federation.”

The military visit schools too. Children in Buryatia spoke of a visit from a wounded soldier who claimed he had fought Polish mercenaries in Ukraine and said the Ukrainians themselves “don’t want to fight and are being forced.”

At least some teachers who have been less than enthusiastic about the changes have been removed, though it’s difficult to know how many. The director of a school in Perm resigned after being criticized by pro-war activists. She’d been reluctant to have classes about the SMO.

It’s also difficult to gauge how parents feel about the introduction of a more militaristic curriculum. Some parents have voiced their opposition, but the majority appear to be supportive of this military-patriotic campaign, if public opinion surveys are to be believed.

State news agency RIA Novosti reported that according to a survey 79 percent of parents support the showing of videos about the war to their children.

Social media comments do suggest that many Russians feel their country is surrounded and ostracized by hostile powers. Its only option is to defend itself. That message – hammered home by the president and state media – is now being taken into Russia’s schools.