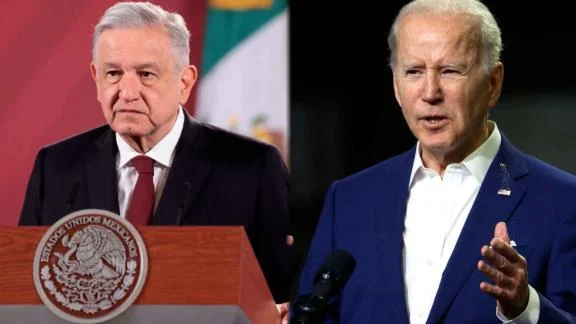

(CNN) – The decision by Mexico’s President to boycott this week’s summit for regional leaders in Los Angeles rendered futile months of work by President Joe Biden and other top officials to convince him to attend.

Now, key nations in Central America are following President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s lead, dispatching only lower-level delegates instead of their leaders. And by the time Biden arrives to the summit Wednesday, questions over the event’s invitation list and attendees will have obscured its larger purpose, a source of frustration to administration officials who didn’t necessarily expect the mess.

The decision by several countries to stay away from the southern California gathering, a protest of Biden’s decision not to invite three regional autocrats, has underscored the struggle to exert US influence in a region that has become fractured politically and is struggling economically.

And it has exposed the difficulties and contradictions in Biden’s vow to restore democratic values to American foreign policy. Even as he takes a stand against inviting dictators to a summit on US soil, prompting anger and boycotts from those key regional partners, his aides are simultaneously planning a visit to Saudi Arabia — seen as a necessity at a moment of a global energy crisis, despite the kingdom’s grave human rights record. White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said Tuesday the kingdom is an “important partner,” though Biden once said it must be made a “pariah.”

In the end, the White House announced Tuesday that 23 heads of state will attend this week’s Summit of the Americas, which administration officials said was in line with past iterations of the triennial confab. One leader who was on the fence, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, will attend and meet Biden for the first time.

Yet the absences of the presidents of Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala are still notable since the United States has worked to cultivate those leaders as partners on immigration, an issue that looms as a political liability for Biden.

Administration officials on Monday dismissed concerns about attendance at the summit, saying they did not believe lower-level delegates from certain countries will alter the outcome.

“We really do expect that the participation will not be in any way a barrier to getting significant business done at the summit. In fact, quite the opposite, we are very pleased with how the deliverables are shaping up and with other countries commitment to them,” one senior administration official said, adding the commitments will range from short term to long term.

And the White House insisted the President was firm in his view that the autocratic leaders of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua should not be invited to participate — even if it means widening rifts with other countries in the region.

“At the end of the day, to your question, we just don’t believe dictators should be invited. We don’t regret that, and the President will stand by his principle,” Jean-Pierre said.

Troubles have been on the horizon for months

Biden, who arrives in Los Angeles on Wednesday, is expected announce a new partnership with countries in the Western Hemisphere during the gathering as part of a broader effort to stabilize the region, according to the officials.

He and his administration have been working since last year to organize the summit, which was formally announced last August. The city of Los Angeles was selected as the venue in January. Biden named former Sen. Chris Dodd, his friend and former colleague on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, as the special adviser for the event.

Dodd traveled in the region to muster support, one of a number of administration envoys to Central and South America that included Vice President Kamala Harris and even first lady Jill Biden. Yet as the summit approached, it became evident an event designed to reassert American leadership in the region was facing serious hurdles.

For weeks before the summit began, López Obrador hinted that he would boycott unless all leaders from the region were invited — including those from Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela, each of whom has faced US opposition because of their human rights records. Other, mostly leftist leaders signaled they, too, may not attend if invitations did not go to everyone.

Administration officials privately cast doubt those leaders would follow through on their threats, suggesting they were instead attempts to play to domestic audiences that are often skeptical of the United States.

During an April telephone call between Biden and López Obrador, the subject of the summit arose. In a readout, the White House said the men “looked forward to meeting again at the June Summit of the Americas,” a sign the administration believed then the Mexican president would attend.

Over the past weeks, Dodd spent lengthy virtual sessions lobbying López Obrador to reconsider his threat of a boycott. Members of Congress — including Sen. Bob Menendez, Democratic chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee — began to publicly agitate against inviting any leaders from Cuba, Venezuela or Nicaragua. And frustration mounted among administration officials that questions over the invitations and attendees were clouding out the summit’s intended goals.

“The biggest problem is that the focus on attendance takes us away from the focus on substance, but that is the logical thing that happens ahead of a summit. It’s like the sausage-making period. We don’t talk much about the substance because the summit hasn’t started yet, we talk only about who might be there,” said Roberta Jacobson, the former US ambassador to Mexico who also served as an adviser to Biden on southern border policy.

Ultimately, the weeks of speculation were put to rest — but not in the way the White House had hoped.

“There cannot be a Summit of the Americas if all countries of the Americas cannot attend,” López Obrador said at a news conference in Mexico City. “This is to continue the old interventionist policies, of lack of respect for nations and their people.”

Mexican President’s absence not a part of a larger rift, officials say

Mexican officials had conveyed their President’s decision to the White House beforehand, and Biden was made aware before the news became public. Instead of meeting at the summit, Biden and López Obrador will meet in Washington next month.

“The fact that they disagree about this issue is now very clear,” a senior administration official said.

Officials sought to emphasize the decision to boycott was rooted in a specific disagreement over the invite list and was not indicative of a larger rift.

“What we have done in recent weeks, going back almost a month now, is consulted — consulted with our partners and friends in the region so that we understood the contours of their views,” the senior administration official said. “In the end, the President decided and very much made this point in all of the engagements that we had … which is that we believe the best use of this summit is to bring together countries that share a set of democratic principles.”

Biden is turning his focus to the Americas after a series of foreign policy crises in other parts of the world, including the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. He completed his first visit to Asia at the end of last month.

That region is one where his animating message of “autocracy versus democracy” is playing out in real time, as China works to make inroads and economically challenged nations look for support from abroad.

In opening remarks Wednesday, Biden will unveil the so-called “Americas partnership” that will focus on five issues, including economic recovery, mobilizing investments, supply chains, clean energy and trade — all with the hopes of strengthening US partnerships in a region many US leaders have been accused of ignoring.

During the summit, Biden is also expected to announce more than $300 million in assistance to fight food insecurity, in addition to other private sector commitments, as well as health initiatives and a partnership on climate resilience.

Caravan highlights need to work fast on migration

As the summit was getting underway, the imperative to make progress on immigration was being starkly illustrated in southern Mexico. A new migrant caravan there set out on foot Monday, timed to bring attention to the issue as leaders were gathering in Los Angeles.

An official with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees said a group of about 2,300 people left the southern Mexican city of Tapachula on Monday heading north. The official said the group is comprised mostly of Venezuelans, but also includes migrants from Nicaragua, Cuba, El Salvador and Honduras.

A regional immigration group, Colectivo de Observación y Monitoreo de Derechos Humanos en el SE Mexicano, said in a bulletin that the group included principally families and children “who demand access to migration procedures and dignified treatment by the authorities.” Tapachula, located just across the border from Guatemala, is a popular way station for migrants traveling from Central America.

Under Mexican immigration laws, migrants and asylum-seekers are often made to wait in the area for several months with limited opportunities for work. Northward caravans of migrants have left Tapachula regularly in the past year, although this week’s appears to be one of the largest. This caravan gathered partially in protest to immigration policies and it would be weeks before they arrived to the US southern border, assuming they all do.

In Los Angeles, Biden and other leaders are expected to agree to a new migration document, dubbed the Los Angeles Declaration, during their Friday meetings. It’s meant to spell out how countries in the region and around the world should share responsibility for taking in migrants.

Officials said they were confident Mexico would sign on.

CNN’s Priscilla Alvarez and David Shortell contributed to this report.