(CNN)As a well-traveled photographer, Pieter ten Hoopen is no stranger to refugee camps.But he never experienced any like the Mayo camp, which is outside the Sudanese capital of Khartoum.

Ten Hoopen was at the camp to photograph a new medical clinic for Emergency, a humanitarian group from Italy. He also hoped to document what life was like for refugees there.

His hopes were dashed, however, when he was told he couldn’t photograph outside the hospital compound.

“I had very, very hard restrictions from the Sudanese government. … They are very well-skilled in keeping the media at bay,” ten Hoopen said.

With no freedom of movement, much like the refugees themselves, ten Hoopen resorted to an old trick he had used before while traveling in Africa. With the help of refugee hospital workers, he built a makeshift photo studio using hospital bed sheets and other materials available.

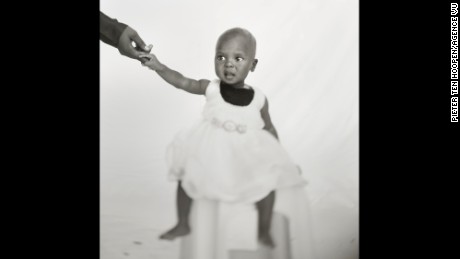

The studio quickly became a sensation. Once hospital employees volunteered to have their photo taken, lines of refugees began snaking around the hospital grounds waiting to have their portraits taken.

One by one, these people sat solemnly to be photographed. It was their time to be acknowledged. There was gravity, earnestness to the way they posed. This was the moment their story would be registered.

“This was one of the reasons why I built the studio: to get more material and more narratives from the people,” ten Hoopen said.

The project quickly became a catalog of the history and identity of the refugees.

The photos span several generations — some of the subjects were born at the refugee camp, some have been there for decades. Women wearing the traditional Sudanese tobe spell out their class and origin by the way it is wrapped. From the Muslim north, women are fully covered — a contrast to women from the Christian south, who we also see represented in these photos.

Whether from Sudan, South Sudan or Eritrea, the faces become, individually and collectively, a portrait of the endless wars that have shaped the Horn of Africa.