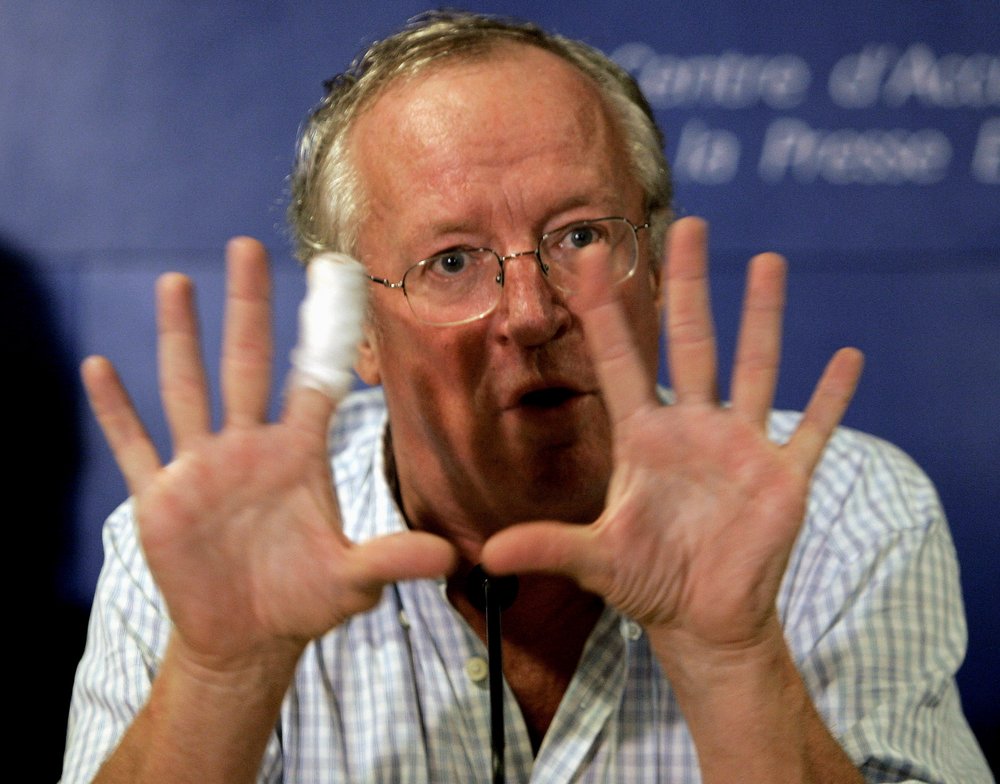

BEIRUT (AP) — Veteran British journalist Robert Fisk, one of the best-known Middle East correspondents who spent his career reporting from the troubled region and won accolades for challenging mainstream narratives has died after a short illness, his employer said Monday. He was 74.

Fisk, whose reporting often sparked controversy, died Sunday at a hospital in Dublin, shortly after he was taken there after falling ill at his home in the Irish capital. The London Independent, where he had worked since 1989, described him as the most celebrated journalist of his era.

“Fearless, uncompromising, determined and utterly committed to uncovering the truth and reality at all costs, Robert Fisk was the greatest journalist of his generation,” said Christian Broughton, managing director of the newspaper.

”The fire he lit at The Independent will burn on,” he said.

Born in Kent, in the United Kingdom, Fisk began his career on Fleet Street at the Sunday Express. He went on to work for The Times, and was based in Northern Ireland, Portugal and the Middle East. He moved to Beirut in 1976, a year after the country’s civil war broke out. Until his death, he maintained an apartment along the Lebanese capital’s famed Mediterranean corniche.

From his base in Beirut, Fisk traveled across the Mideast and beyond, covering almost every big story in the region, including the Iran-Iraq war, the Arab-Israeli conflict, the war in Algeria, the conflict in Afghanistan, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, the Arab Spring and Syria’s civil war. His reporting earned him awards, but also invited controversy, particularly his coverage of the Syria conflict.

A fearless, bespectacled and cheerful personality bristling with energy, Fisk was often the first reporter to arrive at the scene of a story. He shunned e-mail, smart phones and social media, and strongly believed in the power of street reporting.

In 1982, he was one of the first journalists at the Sabra and Shatila camp in Beirut, where Israeli-backed Christian militiamen slaughtered hundreds of Palestinian refugees. Earlier that year, he was also the first foreign journalist to report on the scale of the Hama massacre in 1982, when then-Syrian President Hafez Assad launched a withering assault on the rebellious city in central Syria, leveling entire neighborhoods and killing thousands in one of the most notorious massacres in the modern Middle East.

Fisk was in love with Beirut, the city he called home, sticking with it during the most difficult days of the 1975-90 civil war when foreign journalists fell victim to kidnappers. Back then, he used the offices of The Associated Press to file his stories during the war, where colleagues called him “the Fisk,” or “Fisky.”

In his book chronicling the war, Pity the Nation, he describes filing his dispatches by furiously punching a telex tape at the bureau, which he described as “a place of dirty white walls and heavy battleship-grey metal desks with glass tops and iron typewriters” and a “massive, evil-tempered generator” on the balcony.

“So sad to lose a true friend and a great journalist. The Temple of truth is gone,” said Marwan Chukri, director of the Foreign Press Center at the Information Ministry in Beirut.

Fisk gained particular fame and popularity in the region for his opposition to the Iraq war – challenging the official US government narrative of weapons of mass destruction as it laid the groundwork for the 2003 invasion — and disputing US and Israeli policies.

He was one of the few journalists who interviewed Osama bin Laden several times. After the September 11, 2011 attacks and the subsequent US invasion of Iraq, he travelled to the Pakistan-Afghan border, where he was attacked by a group of Afghan refugees.

He later wrote about the incident from the refugees’ perspective, describing his beating by refugees as a “symbol of the hatred and fury of this filthy war.”

“I realized – there were all the Afghan men and boys who had attacked me who should never have done so but whose brutality was entirely the product of others, of us — of we who had armed their struggle against the Russians and ignored their pain and laughed at their civil war,” he wrote.

His most controversial reporting, however, was on the conflict in Syria in the past decade. Fisk, who was often allowed access to government-held areas when other journalists were banished, was accused of siding with the government of President Bashar Assad and whitewashing crimes committed by Syrian security forces.

In 2018, he cast doubt on whether a poison gas attack blamed on the government had taken place in the Damascus suburb of Douma in 2018. The global chemical weapons watchdog later said it found “reasonable grounds” that chlorine was used as a weapon.

His deep attachment to Lebanon and its people consistently came through his writing. Following the massive explosion that tore through Beirut port on Aug. 4 and destroyed large parts of the city, he wrote a scathing article that summed up the country’s curse and corrupt political class.

“So here is one of the most educated nations in the region with the most talented and courageous — and generous and kindliest — of peoples, blessed by snows and mountains and Roman ruins and the finest food and the greatest intellect and a history of millennia. And yet it cannot run its currency, supply its electric power, cure its sick or protect its people,” Fisk wrote.

Fisk wrote several books, including “Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War” and “The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East.”

He is survived by his wife, Nelofer Pazira, a filmmaker and human rights activist.