Two days after the stifled political march of 6 April, most arrested activists were released by authorities, although a handful remain in detention. In its most recent update, the Front for the Defense of Egypt’s Protesters–a group of lawyers that provide activists with legal assistance–announced that 14 activists remained in detention inside and outside of the capital.

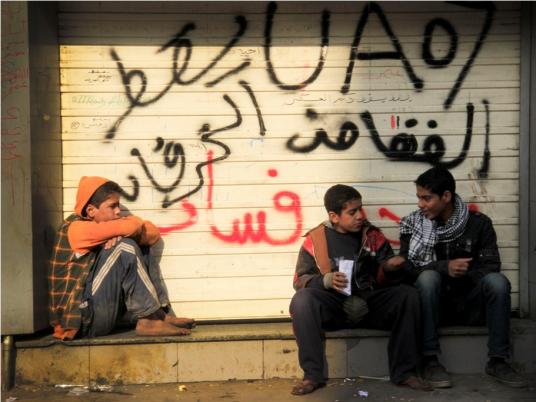

The demonstration, organized by a multiplicity of political groups and parties, had intended to march from Cairo’s central Tahrir Square to the People’s Assembly to protest the longstanding Emergency Law. But omnipresent security forces immediately arrested protesters in different parts of the city, some of whom were beaten up and taken to detention centers, according to reports by human rights organizations.

In its efforts to curb protests, security forces resorted to a series of human rights violations, according to advocates–but experts say the violent reaction served to showcase the regime’s anxieties about the current momentum towards political reform.

“I was meant to meet with a group of four people at the Egyptian Museum and we agreed on the meeting time on the phone. When I reached the museum, a colonel was waiting for me there,” said Abdallah Saadawy, 23, a member of the 6 April political group, one of the march organizers. “He asked me to go home. So I left with my colleagues and we roamed some small alleys, but we were apparently followed.”

Saadawy eventually returned to his initial meeting point at the museum and put on a t-shirt with the 6 April logo on it. “Riot police gathered around me and my friends and beat us up," he said. "I told my friends that we should be careful not to fight back. But they took us to a side street where plainclothes police also beat us up and then threw us into a garage where we were further assaulted.”

Saadawy is one of more than 100 people to be arrested and transferred to a Central Security outpost on the Cairo-Ismailiya road, where they were held in a military prison. Thirty-three of them were later taken to the prosecutors for investigation, while others were transferred to different police stations.

During investigations, the police brought in 23 wounded policemen, according to Haytham Mohamadein, one of the lawyers for the protesters’ defense front, who also works with the Cairo-based El-Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of the Victims of Torture.

“During investigations, protesters were confronted with charges of illegal association, disrespecting the ruling regime, disrupting traffic, exposing citizens’ lives to danger, beating up policemen and taking part in a group that incites hatred of the regime,” Mohamadein said.

At the end of the nightlong investigation, prosecutors ordered the release of the 33 activists, but this did not translate into their immediate release.

“Some of us were then taken to the Qasr el-Nil police station, where we were well treated. Then we were transferred to Al-Khalifa Transfers Center, then to a Giza police station in a truck filled with criminals. In the end, I was taken to a station in Imbaba,” Saadawy told Al-Masry Al-Youm only one hour after his release on 8 April.

After investigations with the prosecutor were concluded, Saadawy and his colleagues were made aware of their release order. As police delayed its implementation, they chanted inside the stations, “Down with Mubarak.”

“At the Imbaba police station, I was told I could only leave if my father comes and gets me, even though I’m over 21. So my dad came and a State Security official told him that he should have raised me better and that he should prevent me from going to protests in the future,” he said. According to Mohamadein, all those detained were released on condition that their parents showed up so police could warn them of further political activities by their children.

A security source told the official Al-Ahram newspaper today that security forces only resorted to dispersing activists after the latter had begun hurling stones at policemen.

The case raised against the protestors is currently pending–a common strategy in protest-related cases.

“Usually, those cases aren’t taken to court and aren’t withheld. If they are taken to court and police are found guilty, they will have a negative political effect for the regime. If they are withheld, protestors will start raising evidence of violations committed against them. So the tendency is to leave them open-ended,” said Mohamadein.

This strategy is one of many intended to consolidate the ruling regime’s authority.

“The brutality shown at Tuesday’s protest shows the state’s concern with the escalation of political opposition into massive protests,” said Mustafa Kamal el-Sayyed, professor of political science at Cairo University. “While the state allows protests based on economic grievances, it is quite wary when it comes to politically-driven protests.”

El-Sayyed noted that the government was not in agreement on how it should deal with this political momentum–a situation manifested in the fact that the Public Prosecutor ordered the release of the activists while police attempted to prolong their detention.

“[The authorities] are quite worried now because the current political momentum has gained considerable support, not only amidst the political and intellectual elite, but also from ordinary people,” he said.

Asked whether the last two days had frightened him off of political activism, Saadawy quickly responded: “I will totally do it again–and get arrested again–until this country is liberated.”