(CNN) ̶ Filmmaking in Iran is not a simple pursuit. There are plenty of ways to fall foul of censors, from negative depictions of society to portraying “unrefined” images.

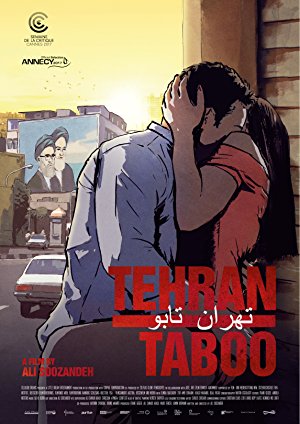

Directors and screenwriters there have become masters in using metaphors to speak their truth. But what about filmmakers from the diaspora? Their editorial freedoms come with other challenges: how to accurately depict Iran while outside it, for one. Enter director Ali Soozandeh and his debut feature “Tehran Taboo,” which has made headlines for its transgressive take on city life.

Soozandeh’s film begins in a familiar but evocative locale: the back of a car roaming the capital. It’s also the primary setting for two classics of Iranian cinema, “Taxi” (2015) by Jafar Panahi and “A Taste of Cherry” (1997) by the late Palme d’Or winner Abbas Kiarostami.

Quickly, this familiarity steers off-road. A taxi driver solicits sex from a young prostitute, who has no choice but to bring her mute child along for the ride. In the middle of a sex act, the driver crashes, distracted — distraught — at the sight of his daughter up ahead, hand in hand with a man. The specter of hypocrisy looms large.

After its debut at the Cannes Film Festival in 2017, “Tehran Taboo” has traveled much of the world and now arrives in the UK. In Iranian cinemas, however, it remains absent.

Set in a middle-class neighborhood and centering on sex worker Pari, well-educated housewife Sara and musician Babak, Soozandeh conjures an intersecting narrative featuring licentious mullahs and backstreet surgeons.

Soozandeh uses rotoscope animation, a process in which the actors were filmed against a backdrop in Europe then animated over in post-production. The effect is a hyper-reality and constructs a Tehran that would never be otherwise filmable: one of private vice and public virtue, and the ongoing battle to keep the two apart.

The director throws the shutters wide on as many issues he can: drugs, drink, extramarital sex, corruption, abortion and suicide. “It is a big taboo in our culture — Iranian culture — to talk about problems in public,” the director tells CNN.

“As a filmmaker who lives outside Iran, you are free to tell the story directly,” he says. The director left his home country in 1995 and now lives in Germany, but his family remains in the Islamic Republic. Has his film caused any problems for them? “Not yet, no,” he says. There has been no request to distribute the film in Iran, but it’s a moot point, he adds — it would never be allowed.

That puts him in august company. Many of Kiarostami’s films never screened in Iran, nor did some of Panahi’s, who now produces movies under house arrest and in defiance of a 20-year filmmaking ban after he was sentenced to six years in prison in 2010, charged with “propaganda against the system,” according to his lawyer at the time.

Soozandeh insists his film is not a reflection of all Tehran, rather “a forgotten part of society.” But having been away for so long, is there a danger that present-day Tehran is markedly different from the city he remembers?

The director kept himself up to date by reading blogs, watching YouTube and interviewing Iranian students, refugees and business people visiting Europe. Some things have changed, others haven’t, he says.

“Young people always find a (space) free of control,” he adds. “You can always find underground parties; you can buy drugs and alcohol everywhere.”

In the film, Pari’s husband is an imprisoned addict, while for Sara drugs are a tempting escape from her domestic confinement. In real life, Iran is experiencing a rise in heroin use, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). According to 2015 government data, the latest published by the UNODC, an estimated 3.3% of 15-64 year-olds in Iran were using opiates — the highest rate of any country listed and more than three times that of the US. Record high opium production in Afghanistan and Iran’s position along the world’s principal heroin trafficking route are underlying factors.

“I think it’s important to be up to date,” the director says, “but the story I want to tell is timeless.”

Online debate around “Tehran Taboo” has been fierce. Reading below-the-line comments on the film’s German Facebook page you’ll find praise (“that Iranians made this film is a good step!”) alongside claims Soozandeh has created “by far the most disgusting and wretched Iranian movie of all time.”

But Soozandeh doesn’t believe “Tehran Taboo” is a political story — nor a specifically Iranian one.

“You can find everywhere these patriarchal structures,” he says. “I got feedback from a woman from Costa Rica. She told me ‘This story could take place in Costa Rica without (the) headscarves.'”

That said, the director wants Iranians in Iran to see his feature. He’s been told copies are available on the black market. So does he mind it’s being watched illegally and without any hope of royalties? Far from it.

“I’m very happy,” he says, smiling. Just as long as it’s being watched.