Almost three decades after the end of the Cold War, secrets from the era of espionage and power games are now resurfacing in Slovenia.

In Kocevje, a forested region in the south, authorities have opened a massive 1950s bunker — complete with tunnels, narrow passages and chunky blast-resistant steel doors — to the public this month for the first time.

Until recently, the existence of the 800-square-metre (8,600-square-feet) labyrinth had still been a secret, albeit not a very good one.

“There have always been rumours about it” among locals because of its location on a sealed-off military base, newly-appointed bunker guide Mihael Petrovic told AFP.

For the underground tour, visitors are taken from the town of Kocevje to the Skrilje bunker in small vans and asked to leave their mobile phones at the entrance.

Those wishing to get a more authentic taste of life under the communist regime can choose to be blindfolded during the 15-minute ride to the hideout.

A portrait of Yugoslav strongman Josip Broz, nicknamed “Tito”, sternly watches over streams of tourists as they amble between dusted-off outdated machines, switchboards and screens.

Although it is smaller than other bunkers, its mint condition provides an excellent insight into Slovenia’s communist past, said Petrovic.

“People now have the opportunity to learn about a period of our history that is far too little known,” he added.

Communist Elite Shelters

Tito ruled over the former Yugoslavia from 1945 until his death in 1980 in Ljubljana, having been named president for life.

He oversaw a Socialist regime that was far from democratic but nevertheless much softer than behind the Iron Curtain.

The leader is admired notably for driving out the Nazi German occupying forces in World War II with his partisan fighters and standing up to Russian leader Joseph Stalin.

But critics accuse him of being responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of political dissidents.

The traces of his controversial reign remain visible throughout countries that once belonged to the republic, which collapsed in 1990.

Up to 50 secret military bunkers were built across Yugoslavia during the Cold War, according to retired Slovenian army officer Marijan Kranj, who wrote a book on the topic.

Tito ordered their construction after he survived a German airborne attack in May 1944 while hiding in a bunker in the Bosnian town of Drvar.

The concrete structures were not only shelters for the communist elite, but also served as arms and ammunition factories, storage rooms and underground air bases.

The expertise of Yugoslav engineers was even exported to non-aligned countries including Iraq and Libya, which today still harbour bunkers dating back to communist times.

Room with a Spying View

But other relics from the communist past are surfacing too.

An hour’s drive west of Kocevje, a fully-equipped surveillance facility was discovered in March at the renowned Hotel Jama, next to Slovenia’s famous Postojna cave, where Tito used to regularly stay and host guests.

During renovation works, hotel owner Marjan Batagelj noticed a locked iron door at the back of the building.

“We couldn’t find a key so I had the lock destroyed. We thought we would find a storage room but instead a brand new world emerged, a space that didn’t appear on any of the hotel plans,” said the 55-year-old, who bought the place six years ago.

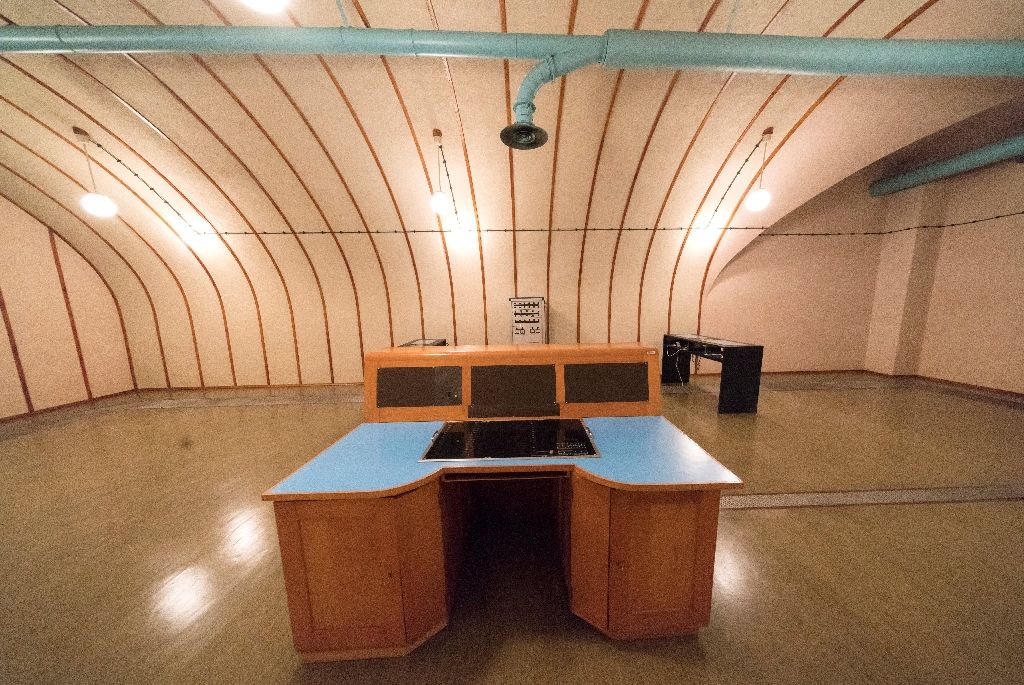

Behind the white door were three connected wiretapping rooms featuring dusty 1970s listening equipment and desks with stacks of papers showing city names and numbers.

Empty boxes of audio tapes lay piled up inside a cupboard.

Batagelj speculated that the rooms were probably built in the late 1960s when the hotel was under construction. “Experts believe it was a key information gathering place for civil and military affairs,” he said.

“This was one of the most important hotels in former Yugoslavia. Tito liked to bring his guests to the Postojna cave and many of them spent the night in Hotel Jama.”

Batagelj said he realised many of his older employees had known about the room for years — agents had to cross the hotel to access it — but never mentioned it. “They were either afraid or too blinded by ideology to speak about it. Even today many think it would have been better not to speak about it at all,” he added.

Batagelj now hopes to turn the space into a “Spying Museum”. “This is a slice of history and there’s no longer any need to hide behind ideological considerations.”