“It was such a long and continuous battle till we were able to free it, and here it is, the street is ours where the Egyptian revolution’s graffiti emerged like a giant from a bottle, turning the city’s walls into public exhibition.”

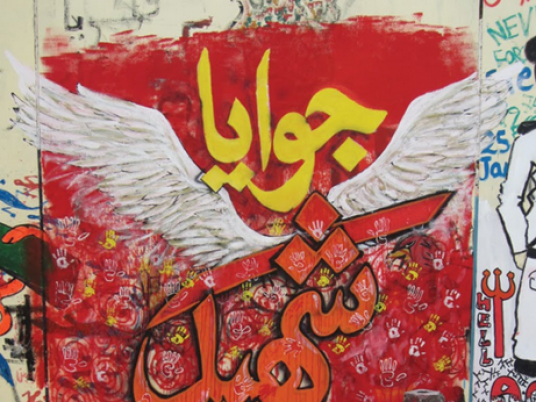

This is how artist and activist Heba Helmi opens the preface of her graffiti book, titled Gowaya Shahid (Martyr inside Me), aiming to immortalize the revolutionary street art on which the government spent considerable sums to clear across the governorates later on.

Readers are taken into a visual journey, tracing the turning-point, subsequent events of 2011 uprising, through a plethora of striking murals sprung up on the country’s walls, in an unprecedented display of public emotions and outrage.

Graffiti, or the stolen art from the state's grip, as Helmi puts it, represents “the voice for who have no voice,” playing an alternative media role for “Maspero’s gates and Minbars (pulpits) of mosques and churches.”

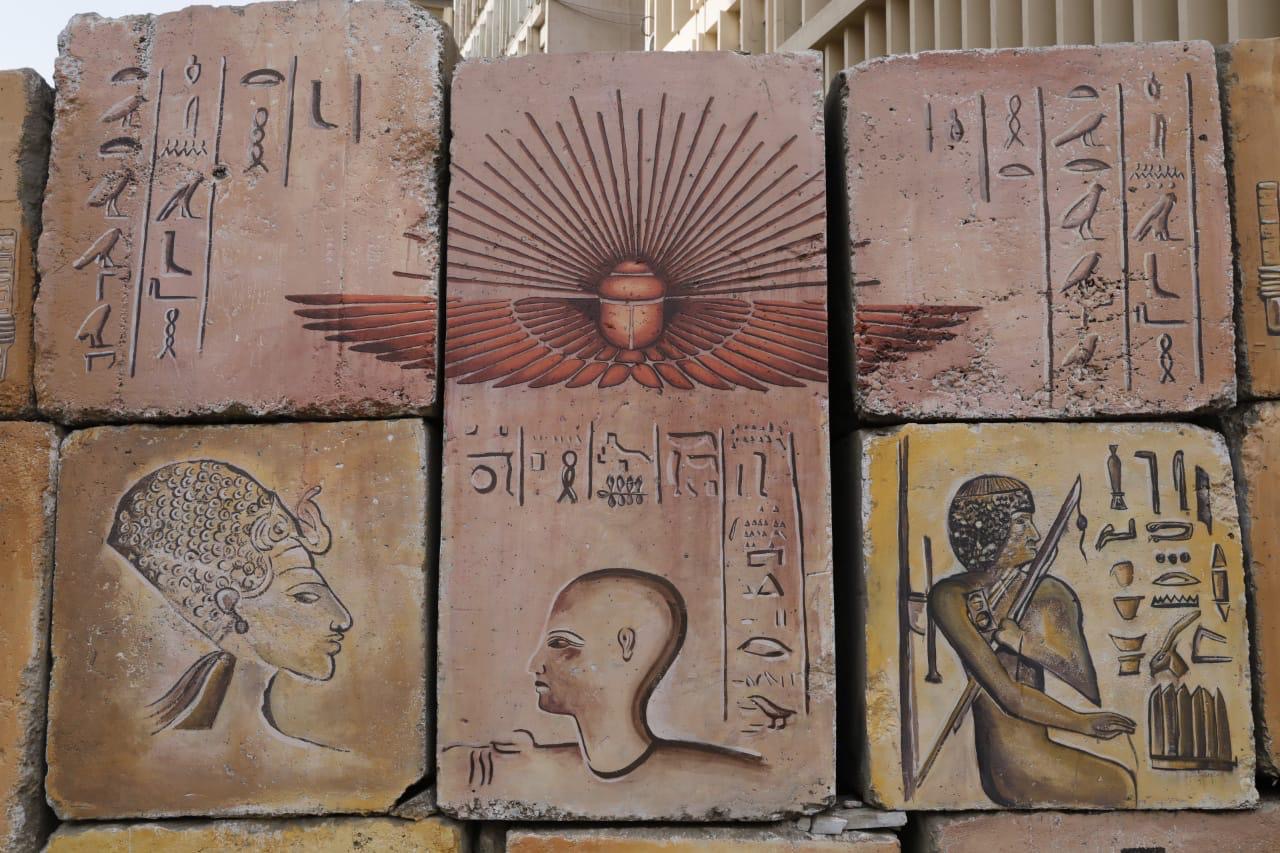

Graffiti art is not merely employed to record, but also to intertwine into mankind history. Helmi points out that the street art dates back to cave paintings of early human, since the Italian word ‘graffiti’ carries the meaning of inscriptions on a wall or other surfaces.

Street art, however, holds within a meaningful message whether political, social or environmental. In this light, Egypt Independent sat down with Helmi to hear how graffiti art is more profound than many give it credit for.

What was the idea behind the book?

I believe graffiti was the sole voice of revolutionaries that courageously stood against the state’s media and its manipulating tools. So, my aim was to chronicle the crucial incidents that took place in the first year after the outbreak of Egypt's 25 January revolution and the response of 'man in the street' mirrored in extremely creative and expressive street artworks.

Since you dedicated a section, named Noon al-Niswa, for women in your book to show their significant role in the revolution as well as their unbeatable perseverance during daily life difficulties, what is the mural you like the most in this section?

One of the most outstanding street artworks in the book is Saydaat al-Anbeeb (women cylinders) painted by Hanaa al-Degham on the Mohamed Mahmoud wall. The mural depicts a pyramid of gas cylinders carried by poor women on their heads and held on men’s shoulders. The heap, actually, embodies the daily burdens the underprivileged bear and how Egyptian women are as tough as their male counterparts when it comes to a family’s sufferings.

What was the source of inspiration for al-Degham’s mural?

Hanaa was going to cast her vote in 2011 parliamentary elections in Luxor. Then, she noticed that gas cylinders queue was much longer than the queue stretching in front of the polling station. This indicated that even after 2011 uprising, things stayed the same; politicians are still power hungry while turning a blind eye to the poor’s daily struggle for basic needs.

Why did Graffiti art strongly emerge in Egypt during the revolution?

There was Graffiti in the country, as a matter of a fact, before the revolution, but on a small scale. Before the revolution, Egyptians were not allowed to draw on walls in order to voice their own thoughts freely. If someone took a picture in the street, a police officer would show up out of the blue and ask for ID or license. After the revolution, however, nothing has been stopping Egyptians from standing up for their rights. The walls of the city as if were gained back to their owners who are afraid to speak their minds no longer.

What distinguishes your book the most than the other published Graffiti books earlier?

The book adopts a storytelling approach recounting the incidents through vivid pictures accompanied with explanatory texts based on personal testimony and how I perceive them through my own eyes. I didn't want the book to be just a display of sereis of pictures like the previous ones. In other words, if a person didn't witness the events, would still comprehend the message that lies within each mural. I also interviewed well-known graffiti artists in person and some bloggers via the Internet. However, there is a batch of ‘unknown soldiers’ who were behind the graffiti art that swept the country.

How did you choose the title of your book Gowya Shahid?

The book is named after a mural painted by Mohamed Gaber on the Mohamed Mahmoud wall. This mural is among other street paintings that had been erased after former president Mohamed Morsy rose to power. The name is quite captivating in a sense that despite feuds and debates taking place everywhere surrounding politics, martyrs’ rights have been the only factor bringing people of different political ideologies together.