Egypt is home to dozens of museums, from downtown’s hugely popular Egyptian Museum to the strange and too-often overlooked Agricultural Museum. Each Wednesday, as part of a new series focusing on the diverse world of Egyptian treasures new and old, Al-Masry Al-Youm will take a close look at one of these museums.

This week, we examine the Museum of Islamic Art, whose renovation process is perhaps as interesting at its artifacts.

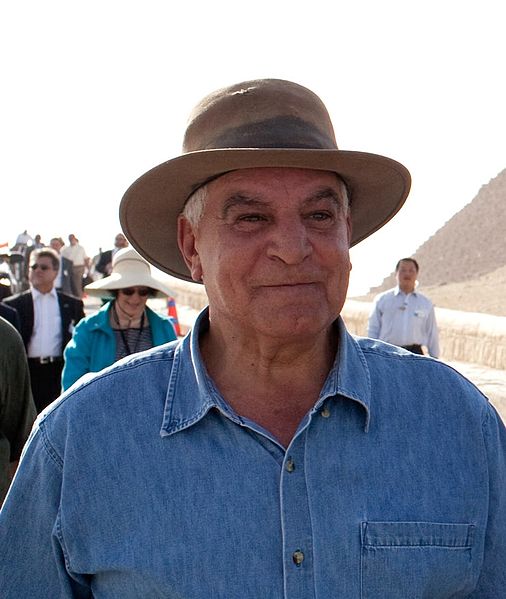

In general, a museum collection is arranged in one of two ways. Either the pieces unfold chronologically, according to the year they were made, or with narrative, attempting to tell a story or teach a lesson. These days in Egypt, chronology is out and narrative is in, at least as long as Zahi Hawass, the secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SAC), has anything to say about it.

“Chronologically is bad. It doesn’t teach people,” Hawass said from behind his desk in the SCA building in Zamalek as countless assistants materialized from various doors. A red plastic button with the word “bullshit” sits on his desk. One gets the sense that the official makes frequent use of this toy.

The Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo certainly has a story. It is one, of course, of the artifacts it holds–the largest collection of Islamic art in the world, covering 1400 years of Islamic history from Umayyad to Ottoman. It is a story of advances in medicine and the spread of religion, of funerary traditions and science, of changing social mores.

It is a story of inclusiveness. Along with Egyptian artifacts, which are largely housed in the north wing, there are Turkish, Syrian, and Indian pieces; the work of Muslim artists is presented alongside their Christian and Jewish contemporaries. A favorite of Mohamed Abbas Selim, the museum’s general director, is a turban dating to 707 CE (88AH on the Islamic calendar) decorated with a gold stripe and a line of intricate calligraphy embroidered on the cream-colored fabric by Samuel Ibn Marcus, a Christian.

It is also the story of an arduous seven years of renovation, of crumbling walls and poorly-maintained artifacts, of arguments and last-minute changes, of definitions and limitations of Egyptian cultural heritage, of what Hawass called “the most difficult job of my life.”

The Museum of Islamic Art was first established in 1881 in al-Hakim mosque and moved in 1903 to the building that houses it today, a grand neo-Mamluk structure overlooking Old Cairo whose second floor is home to the national library, the Dar al-Kutub al-Masreya. As the collection grew, the museum became less welcoming, its objects thoughtlessly compiled and the building poorly maintained. By 2002 there were plans for two separate museums–one for architecture at the Citadel and one for art in the current building–but Hawass, who had just been appointed to the SCA, rejected this separation, arguing that Islamic art and architecture are far too intertwined.

It was obvious to Hawass that, in order for the museum to compete on both a local and international level, there had to be serious changes. The entire building, not just the collection itself, would be renovated. Each success exposed new challenges. “Like a sick man, you try to change the liver and the stomach appears,” Hawass said.

Hawass asked himself, “How can I make the museum brilliant?” The answer was outside of Egypt. Hawass hired French designer and museographer Adrien Gardère–who had worked on several successful temporary exhibits in Cairo including “Parfums d’Egypte”–and secured funding through the Agha Khan Foundation (AKF). He also hired a Spanish restorer Eduardo Porta to head one of the museum’s most challenging projects: the complete renovation of a central Mameluk fountain which involved disassembling the mosaic and restoring it off sight before painstakingly reassembling it in one of the museum’s central galleries.

Gardère was scheduled to work on the museum for three years, but it would be twice that before he would leave the project, and not without the sense that he had overstayed his welcome.

Gardère assumed what he thought would be full artistic control of the collection’s redesign and the building’s renovation in early 2004. Determined to “respect the architecture as the part of the collection itself,” he began tearing down walls, restoring light and streamlining the display which was overcrowded with works he considered “irrelevant” to the story of Islamic art.

Interiors in Cairo are often kept dark in order to shield inhabitants from dust and heat. Gardère opposed this, feeling that natural light is “a key element of Islamic art and architecture.” By covering the windows with ornate, mesh screens, he incorporated the city into the space. He worried that the high ceilings and open rooms would create a series of hallways, hurrying visitors past the pieces, so he arranged the artifacts beneath the natural crossings of the ceiling beams, central in each room. According to Gardère, his proposal was approved by Hawas, the curators, and the Agha Khan Foundation.

The museum seemed destined to take over Port Said street, in the name of beautification and gentrification. According to Hawass, a neighboring gas station became a garden and other buildings, some of them private homes, were converted into a parking lot for tourists visiting the notoriously congested area. ”The museum will be the jewel in the heart of Cairo,” Hawass exclaimed. But first, it seemed, that heart would need a slight tuneup.

The design is meant to entice visitors who, once there, will feel that they can access the art. We want “everyone to understand, whether they are educated or not educated,” explained Selim. This popular approach is important to Hawass, whose impression of his own notoriety is realistically two-fold. On his reputation as a reclaimer of Egyptian artifacts abroad Hawass admits, not without pleasure, “People hate me all over the world.” In Egypt, ”I walk past bawabs and they stop me, ask me about archeology.”

This pride in Egypt’s past and interest in improving its present is complicated both by Hawass’s overseas hire of Gardère and his own admission that his know-how comes not from his time in Egypt but the US, where he studied at the University of Pennsylvania.

The intercontinental collaboration had its troubles. Hawass, who calls himself the “owner of the place,” characterized it thusly: “You, as a designer, cannot tell me what to think.” And, like the extent of the building’s disrepair, the clashing visions would show themselves most clearly not in the exhibitions, but in the walls.

Gardère’s final step to brighten the museum was to paint it white. “Islamic art deserves light,” he said. Any color in the building would come from the diverse artifacts. But this starkness did not appeal to Minister of Culture Farouk Hosni, who withheld his approval of the renovation until the walls were repainted, which they were this past summer, to a slate gray.

Gardère, speaking from his studio in Paris, admitted that it was within the rights of the Egyptian government to make the change, although he considers it to be a mistake. Gray walls “lowered sense of height and volume, and eliminated the artifacts. I think darkness has nothing to do with Islamic art.”

But Hawass, unsurprisingly, supported the minister of culture. “Hosni is an artist,” he said. Changing the color was a “brilliant idea.”

After Gardère left, Mahmoud Mabrouk, a local artist and advisor to Hawass, took over, leading a team to rethink the exhibits and the accompanying labels. Some of what Gardère cut was restored, including a collection of swords and textiles. The label copy is still in the process of being fact-checked and revised. Hawass has invested in local talent; he is currently training 2000 people who can “be better than me,” and to whom he can entrust projects in the future.

“If you can be good,” Hawass said, “you can compete.”

The museum’s official reopening will be celebrated with a lavish party on 25 October, complete with musical performances and the First Lady. Gardère said he would be happy to go, if he is invited.