Nabil Bahgat, reviver of folk puppetry, seeks to champion Egyptian traditions

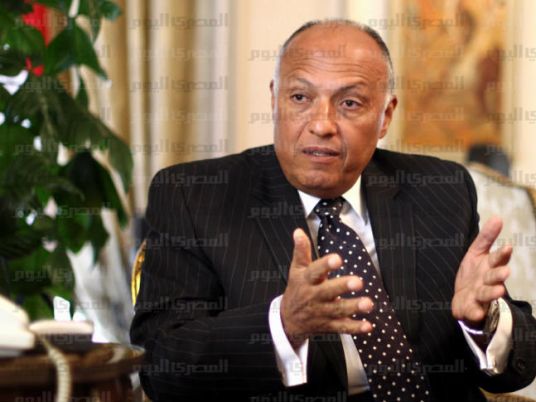

"To me, the Egyptian folk doll provides a sense of belonging. They reflect the Egyptian identity, one that is constantly challenged by other cultural trends," explains Nabil Bahgat, founder of the WAMDA troupe for shadow and ‘aragouz’ (wooden clown) folk puppetry, and head of the Beit Al Seheimi cultural center.

Bahgat is the driving force behind the annual forum for folk dolls, now in its third year and gaining in popularity as a highlight on the country’s cultural calendar.

Having completed a master’s and PhD in Egyptian Drama, Bahgat taught Arabic theatre at Helwan University. His fascination with folk heritage deepened after examining Cairo’s ever-changing streetscape.

"I was walking in downtown when I noticed a billboard reading ‘Shahrazad’ with the photo of a girl dressed in a bikini. And I realized that all the mannequins in the shop windows had foreign features, as if Egyptians lacked their own," he recalls."You can see a veiled girl dressed in a tight outfit, reflecting neither our culture nor the latest fashion. Shops offering food have morphed into take away joints, while ahwas have been transformed into coffee shops that serve foreign beverages instead of local ones," he adds.Bahgat decided to take a stand against the changes he was witnessing by reviving a tradition from the core of Egyptian culture.

"When I turned to folk-literature scholars and asked them where the remaining aragouz and shadow puppeteers could be found, I was told that they had long gone.

But Baghat’s persistence encouraged him to wander around Egypt, attending moulids – religious festivals commemorating saints – which had been a typical venue for puppet shows.In this way in 2003 he stumbled across the talented puppeteers Amm Saber and Hassan Khanoufa. Amm Saber is the oldest aragouz puppeteer, while Hassan Khanoufa was the last shadow puppeteer, who sadly passed away shortly after Baghat met him.

In that same year, Bahgat founded the WAMDA troupe as a response to the decrease in the number of moulids, the lack of public performance spaces, and a decline in awareness of the importance of the art form itself.

The troupe includes several of Bahgat’s young college students and it makes regular workshops and performances based on new themes while preserving the old techniques and heritage.WAMDA started out with 40 nights of street performance, followed by 30 more performances in Al Azhar Park that proved popular with audiences: it was a hit. Awarded the prestigious Future Leaders International Fellowship from the Theater Communications Group (a non-profit organization aiming to bring together performance professionals separated by geography), Bahgat created a permanent Egyptian puppet exhibit at the Atlanta Puppet Center as well as running a series of seminars, lectures and workshops there, before returning to Egypt to create in 2006 the first shadow puppet festival and forum on Egyptian folk dolls.

Bahgat also created five photography exhibitions depicting folk arts and crafts, and is currently editing nine documentary films on folk art, in addition to writing a book on aragouz puppetry. But his ambitions to revive the art of folk puppetry don’t just stop there.

"My dream was to establish a permanent performance space for aragouz and shadow puppeteers, and to be able to secure them regular wages," said Bahgat. Last year the Ministry of Culture granted Bahgat this wish, with the establishment of Beit Al Seheimi, which now serves as a showcase for folk arts and a permanent exhibition of Egyptian folk dolls, as well as playing host to a weekly performance of shadow and aragouz puppet shows.

Fourteen-year-old Ahmed Mustafa, visiting the space for the first time, is thrilled to see the original model of his favorite puppet, the aragouz. Mustafa purchased a similar red puppet and the two are rarely apart."It makes me happy because it enables me to express myself," he explains.

Yet the aragouz, like the rest of the Egyptian folk dolls, are more than just dolls: they have for many years reflected contemporary views during particular eras of Egypt’s history.

"Though we have no historical evidence to mark when it started in Egypt, the first reference to the aragouz hand puppet was in the eleventh century," explains Bahgat.

The aragouz, a witty character sporting a distinctive red outfit complete with cone-shaped hat and whistle-like voice, roamed the streets and moulids of Egypt, accompanied by a group of twelve co-stars, to appear in a series of classic plays such as ‘The Bag Thief’ and ‘The Aragouz and His Wife’.

Other puppets depicted various segments of society, such as the soldier who represents political authority, the sheikh who represents religious authority, the artist, and the beggar.

"For a long time, theatre puppet art was used for political purposes, namely to expose the corrupt rulers of the land. The aragouz has always been the voice of the people, defying tyrants and corrupt rulers," Baghat explains.

Shadow puppet performances have also taken place in Egypt for centuries. Abdel Hamid Younis’ book on shadow puppetry reads: "This form of art first flourished in the Far East and Persia, where it originates. In time it made its way to Egypt with the Fatimid era and it remained here".

All shadow puppets are decorated with typical Islamic art patterns and motifs, which reflect the Arab and Egyptian legends they portray.

Made originally out of animal leather, during periods of decline cardboard became a more affordable substitute. In its recent revival of the art form, the WAMDA troupe uses new designs made from leather and as well as reviving the old babat (scripts) it has generated new ones.

"I dream of a world where the Egyptian aragouz is heralded as a spectacle in the same way as the characters of Disney," says Nabil Baghat.

Reflecting on his first performances abroad, Baghat likens the risks he took to taking a chance on a dying man in an intensive care unit, who everyone is convinced is dead.

"The man lives to this day, and he is carried from me to you, here and now. This is the power inherent in our folk art," Bahgat says triumphantly.