“He swore it all took place under a giant glass dome,” reads a sentence printed in silver below a photograph of two cable cars, reminiscent of 1970s space fantasies.

The humorous image is one of 20 framed photographs that lined the entrance of the Townhouse Gallery’s factory space as part of the PhotoCairo 5 exhibit. But it’s not all the same for the rest of the photos comprising Basim Magdy’s series, titled “Every Subtle Gesture.”

Some photographs are surprising, like that of a wooden ramp leading to a tower-like building under construction, accompanied by the sentence, “History is written by construction workers and priests.” Others are slightly depressing, such as the statement: “There is no fun here. There is no entertainment,” juxtaposed with a photograph of four colorful spotlights from a street fair.

But they are all intriguing, gradually helping us piece together the loose narrative Magdy seeks to present.

Magdy started working on “Every Subtle Gesture” in late 2011 for his solo show “When Thought Evades a Great Thinker” at artSumer, Istanbul. Like many Egyptian artists, he was not sure how to proceed with his work, given the events of the past year.

So he started revisiting his archive of photos that he had been taking since 1998 with “no direct relationship to his artistic practice.”

Looking at the collection five times every month, he saw threads of a possible narrative looming, and began making different selections that play on ideas of memory and storytelling.

But the artwork plays on our personal memories and imagination even more than that of the artist.

Juxtaposing the selected images with open-ended statements such as “She fell for a national hero who cooked three wolves in a pot,” and “We construct intricate alibi to make up for our absent mindedness,” Magdy writes himself out of the images, and offers instead a story of “a community, a group of people living together, the I, he, she and us … who continue to try and fail, and try and fail,” he explains. “There’s no end, but more attempts.”

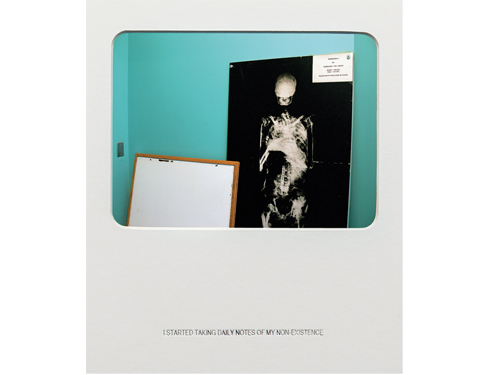

And it works. With the exception of very few, we cannot tell when, where or on what occasion the photographs were taken. In one, we recognize a boat sailing the Nile or the 2005 X-ray scan of Egypt’s boy king, Tutankhamun. But these seemingly initial clues are immediately refuted by the corresponding statements he writes for each image.

Under the picture of the boat, we read the words: “Every subtle gesture reflected a growing revolution,” and “I started taking daily notes of my nonexistence” under the X-ray scan.

“I am not interested in people knowing when, where and why these photos were taken,” says Magdy. “What’s important to me is that people see an image. … It would make them curious, and the sentence gives some information that takes them to another place. … It’s an image of a place that is not specific; it will vary from one person to the next.”

With every new image he adds to the collection, our perception of this unspecified community and where each one of us stands in relation to it — despite our different backgrounds — becomes stronger.

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent's weekly print edition.