TUNIS – Right in the heart of Tunis, a dozen of bearded men, some dressed in robes, others in tunics, sat outside the Salafi-controlled al-Fateh mosque to sell various Islamic products such as religious books, men’s hand-knitted caps and prayer carpets as the full female Salafi outfit of dark robes and the niqab was on display.

Across the street, an ad for Tunisia’s first Salafi party hung between two streetlights. “The Sharia is our path and reform is our choice,” read the white banner.

The scene was unthinkable under the rule of the deposed president Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. Like his predecessor Habib Bourguiba, Ben Ali sought to derive legitimacy from secularizing the Tunisian society and combating Islamism.

But as soon as last year’s popular uprising forced him to flee, Tunisia’s six-decade-old secularization project has found itself face to face with a robust Islamist movement that sells itself as the actual representative of Tunisia’s Muslim society and as the antithesis of the ancien regime’s staunch westernization.

The vigor of this movement was well manifested in the elections of the National Constituent Assembly tasked with drafting the constitution. The nation’s oldest and most moderate Islamist organization, Ennahda, won 89 out of 217 seats, scoring the highest number of votes and emerging as the key player in post Ben Ali Tunisia. To prove its commitment to consensus-building, it formed an interim coalition government with another two secular parties, which has been dubbed as the Troika.

Egyptian pundits have long looked up to Tunisia, contending that its Islamists and secularists could overcome their ideological differences to move forward with democratization. They usually cite Ennahda’s progressive outlook. Yet, the situation in Tunisia today is not necessarily as rosy.

Although Ennahda is widely seen as far ahead of the Muslim Brotherhood in terms of its commitment to democracy and liberal values, and despite the absence of far-right Salafi parties from decision-making bodies, Tunisia has not been spared the secular-Islamist divide marring Egypt’s transition to democracy.

An Islamist-secular divide has been deepened by an emerging conservative wing within the Ennahda and a bourgeoning Salafi trend. Both find themselves in confrontation with Tunisia’s ardently secular constituency, which unlike its Egyptian counterpart refuses any compromise on secular values or aspects of modernity.

The two-winged Ennahda

After more than two decades of living in the diaspora or languishing in Tunisian prisons, thousands of Ennahda leaders and members rallied in the capital for their first convention since the revolution in mid-July.

Amid claps, Rachid Ghannouchi, the group’s re-elected president and founder, walked in to address thousands of fervent members of both genders.

The 71-year-old leader seized the opportunity to re-emphasize the Ennahda’s moderate line of thought. “[Ennahda] does not claim to be speaking in the name of Islam,” he told the audience.

“We did not make any demands for Islamic Sharia [to be implemented] since we engaged in politics. Our understanding of Sharia does not mean laws that shall be implemented but we understand it as a comprehensive principle [that comprises] justice, mercy and human values that adapt to all changes that society goes through,” added Ennahda’s ideological leader.

He went on, stressing his group’s efforts to build a coalition government with secular parties after last year’s elections, warning against ongoing ideological divides.

“This polarization is against democracy and against the revolution. It only benefits the revolution’s enemies,” he contented.

Only a few meters away from Ghannouchi, 23-year-old Ennahda member Hamdy al-Qassemy filmed the event, dressed in a black shirt and white Capri pants.

The lightly bearded young man is a firm believer in Ghannouchi’s school of thought. His colossal work, “Public Liberties in Islam,” which provided an elaborate reconciliation between Islam and several liberal values, encouraged Qassemy to join the group.

To him, ongoing ideological polarization is due to secularists’ intransigence.

«The problem with Tunisian secularists is that they do not only want to separate religion and politics but also to separate religion and the society,” complained Qassemy.

Tunisia still lives the legacy of the sweeping secularization initiated in the 1950s by its first president, Bourguiba. While secularists perceive his policies as reflective of a modern understanding of Islam, Islamists hold him as Tunisia’s most anti-Islamic figure.

By importing a French version of secularism, Bourguiba had worked steadfastly to marginalize religion and disseminate western values. Among moves deemed outlandish were his calls on Tunisians not to fast during the month of Ramadan in order to maintain their productivity, a ban on the veil, the abolition of Sharia courts, a ban on polygamy, and the closure of the Islamic University of al-Zeitouna. Such policies had eventually led to the secularization of large segments in the Tunisian society.

According to Atef Dhibi, an Ennahda supporter, there is an “anti-Islam movement” in Tunisia led by some of the country’s secularists. He refers to a controversy in an art gallery last month as a manifestation of this war.

Islamists had taken to the streets to protest the displaying of what they deemed “blasphemous” paintings.

“It is hard to imagine something more hostile to Islam,” complained Dhibi who is also the vice-president of a civil society organization for local development. The protests had culminated in a two-day riot. Eventually, the Ennahda-led government had imposed a series of curfews across the country. Ghannouchi had condemned the violence but had reportedly expressed his opposition to «attacks on the beliefs of Tunisians.» In the meantime, secularists dismissed the violence as a violation of freedom of expression.

A similar outrage had erupted last year over the airing of the French animated movie “Persepolis” on a private television channel. Islamists demonstrated against the depiction of God, which is forbidden in Islam. Salafis were blamed for damaging the house of the channel’s director with Molotov cocktails. Earlier this year, a court had found the director guilty of “disturbing public order” and “threatening public morals” and fined him US$1,600.

“The Tunisian people have been split between Muslims and non-believers, it is a purely religious war,” argued Dhibi, who is also a PhD candidate in public policy.

“The polarization in Egypt is purely political, but in Tunisia, it is religious,” he added. “In Egypt there is no party that is hostile to Islam or Christianity.” In contrast, he lists the coalition of secular parties known as “the Democratic Modernist Pole” as the spearhead of “the war on Islam”.

Mohamed Kerrou, a political science professor at Al-Manar University in Tunis, argues that there is a more radical strand within Ennahda, which is contributing to the deepening Islamist-secular divide.

“Ennahda has one political and another missionary wing,” he said. “The missionary wing within Ennahda is Salafi. It mixes religion and politics and refrains from any confrontation with the Salafi current because it supports Salafism,”

Although the party remains dominated by the liberal political wing, Kerrou says that the Salafi camp strives to stretch its influence.

“This Ennahda missionary wing had filed a suit to reopen the Islamic University of al-Zeitouna in an attempt to gain legitimacy in its conflict against the party’s political wing and to stretch its hegemony over the society,” explained Kerrou. The case was won and the religious university was re-inaugurated in May.

The conservative wing is represented by religious leaders including Sheikh Sadek Chourou, Sheikh Habib al-Louz and the high education minister al-Monsef Ben Salem, according to Kerrou. They are all members of Ennahda’s highest decision-making body known as the Shura Council. Earlier this year, Louz had defended the inclusion of the Islamic Sharia in the new constitution in a televised interview, contradicting the official discourse of the group.

Ben Salem had been the subject of secular outrage on more than one occasion. Last year, a video that depicted him contending that Bourguiba had Jewish ancestry and sought to implement a Zionist plan to westernize Tunisia went viral online.

He had also elicited a stir by dismissing a work by one of Tunisia’s highly-respected writers for allegedly mocking a Quran teacher.

Recently, Abu-Yaarob al-Marzouqy, an advisor to the prime minister and an Ennahda hawk, has made headlines by reportedly dismissing tourism as a form of “secret prostitution.” Leaders of the tourism industry have vowed to sue him.

Finally, the party’s latest convention has brought more discomfort to secular Tunisans. By recommending the criminalization of “the infringement on sacred values,” the party’s closing resolution has proved quite alarming.

“What is the meaning of sacred values? And who decides what is sacred? This takes us backward and infringes on liberties,” argued Khadija Sherif, a sociologist and a veteran feminist.

The bourgeoning Salafism

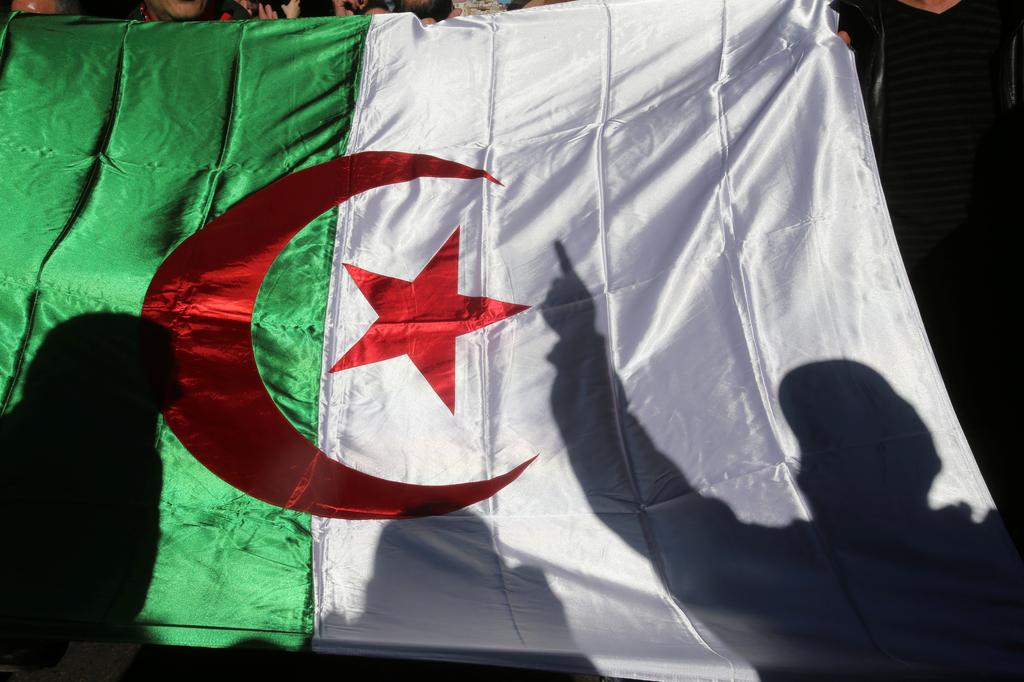

Tunisia’s rising Salafi groups have added more complexity to the secular-Islamist divide.

“Salafism became visible after the violent acts that erupted in the first three months that followed the revolution. It began by protests outside Jewish worship houses and churches to denounce Zionism and the crusades,” said Kerrou.

Meanwhile, Salafis sought to close down legally-established prostitution houses, he added.

“Most of these houses were closed down by force and the prostitutes were expelled,” Kerrou continued.

Tunisia has two strands of Salafis. The first type, Jiahdi Salafism, adopts violence as a means for change.

Although Jihadi thought had penetrated Tunisia long before the revolution, it took no organizational form until Ben Ali was ousted, said Kerrou.

Ansar al-Sharia stands as the main jihadi organization in the country. The group is led by Saif Allah Ben Hussein whose nom de guerre is Abu Ayad al-Afghani. He had fled from Tunisia in the 1990s and ended up in Afghanistan where he lived until last year’s revolt.

“Rumor has it that he had sworn allegiance to Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri but he denies that,” added Kerrou.

The group claims to have 15,000 members but Kerrou argues that the membership does not exceed 5,000. Although the organization has no official status, it convenes in public, added Kerrou.

“Until now, Abu Ayad al-Afghani says that Tunisia is not a territory for Jihad but for missionary activities,” said Kerrou. However, the group’s members have been allegedly involved in violent acts, added Kerrou.

On the other hand, political Salafism refers to parties seeking to bring about change by peaceful political means. Two parties represent this strand: the Reform Front and Al-Tahrir. While the former envisages the establishment of an Islamic state where Islamic law shall be enforced, the latter opts for the revival of the Islamic Caliphate.

Both were approved earlier this summer by the Ennahda-led government, as part of the group’s proclaimed policy to incorporate Salafis in the political process. Ennahda hopes that such incorporation would moderate these groups.

Mohamed Khouja, the leader of the Reform Front said that his group had filed a request to the National Constituent Assembly to add a clause to the constitution stipulating that the Islamic Sharia be the sole source of legislation.

“We presented this request several times but it was not heeded. Nahda has brought it up [in the assembly] but at the last minute the Troika reached a consensus and this demand was dropped,” said Khouja, a former Jihadist who was jailed under Ben Ali.

“If we make it to the parliament in the next elections, we may call for the amendment of the constitution. We are a Muslim society and the Islamic Sharia shall be respected,” added Khouja.

The inclusion of Islamic law in the Tunisian constitution might be quite a divisive endeavor given the country’s historical and cultural context. Unlike Egypt, Tunisia’s post-independence constitution never mentioned Islamic law. While Egyptian secularists have already endorsed an old clause stipulating that the principles of Islamic Sharia shall be the primary source of legislation, their Tunisian peers are far from making such an ideological concession.

Tunisia’s secularists: Uncompromised gains

The unique status of Tunisian women lies at the heart of the Islamist-secular divide. Since Ennahda has risen to power, secular feminists have been weary that the new ruling elite might abolish a plethora of laws that grant women exceptional rights unheard of in most Arab and Muslim countries.

“[Ennahda] cannot achieve an Islamic society without broaching women’s status. Women stand as one of the pillars of their project. This is what scares us,” Sherif, former president of the Association of Democratic Women.

Among the legislation that secularists deem sacred are codes that that prohibit polygamy, condone adoption, ensure women the right to abortion and recognize children produced by extra-marital relations. All these laws are believed to contradict Islam.

Feminists were alarmed by several statements made by Ennahda leaders that warned of a possible revision of laws widely canonized by women.

“As soon as [Ennahda] reached power, Ghannouchi spoke of the banning of adoption and he wondered why polygamy shall be banned arguing it is a personal choice,” Radhia Nasraoui, a human rights lawyer said.

Such statements had provoked staunch reactions from Tunisian civil society.

“Anything that touches women always provoke reactions,” said Nasraoui.

Eventually, Nahda had fallen silent on the matter.

“They say one thing and then when they find reaction to that, they back off,” said Nasraoui.

For Sherif, Islamists are not only required to keep all “women’s gains” untouched but to heed further women’s demands to revise Islamic inheritance laws that grant a woman half a man’s share and to change clauses in the personal status law that sill hold the husband as the head of the family.

“Women contribute to the household’s economy. There is no reason why they should not get the same inheritance as men,” added Sherif.

In theory, only three months stand between Tunisians and the end of the transitional period. By the end of October, the NCA shall finalize the constitution and parliamentary elections will be called for. But, both secularists and islamists expect the deadline to be stretched given this ideological divide.

In the meantime, some expect more violence to ensue.

“Salafis will step up their operations in an attempt to control the public sphere and curb liberties,” expected Kerrou. “[because] this public space in Tunisia has been secular for decades thanks to Bourguiba and the [building] of a modern state.”

This piece was originally published in Egypt Independent’s weekly print edition.