If you’ve ever been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and looked at the labels describing its many Egyptian artifacts, you would think they were all discovered in Europe. The Rogers Fund, gifts of Edward S. Harkness, gifts of the Egyptian Exploration Fund (a group of wealthy English travelers and adventurers) and the museum itself, among others, are thanked for bestowing such an expansive collection of antiquities to visitors of the Dawn of Egyptian Art wing. Apparently, the dawn of Egypt came when Europeans arrived to witness it.

At 9:30 am on a mid-July day, the Met was already filling with tourists and their cameras. After a very long year living in Cairo, I went into the Egyptian art wing hoping to find another reason to be impressed by this ancient part of the world where the Nile meets the Mediterranean. I wasn’t disappointed.

The wing is a shrine to all that is beautiful in Egypt’s history, and tourists come to pay pilgrimage. Egyptians with “Call me Dave!” or “Hi, I’m Peter!” pinned to their chests speak with Queens, a New York borough, and New Jersey accents. They lead large groups through the warrens of the exhibit, weaving biblical history into their explanations of certain objects and antiquities.

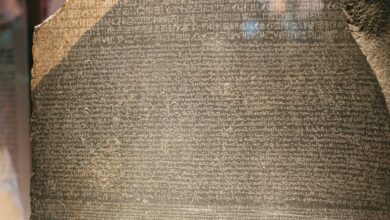

Each item is carefully displayed. Walls have been lovingly shellacked to house the small shards of a mural that once decorated the inside of a tomb. They are spaced far apart from each other; curators and Egyptologists have filled in the lacunae with simple line drawings that illustrate the complexity of the mural. A large plaque below the piece explains where it came from, who discovered it, what the hieroglyphs mean and why these paintings were created in the first place.

Another wall is home to a beautifully transcribed length of papyrus from the Book of the Dead. After thousands of years, the black ink inscribing the pages still looks dark and unfathomable, almost wet on the onionskin parchment. This papyrus snakes purposefully through a long hallway. Small excerpts are translated throughout, giving the reader a glimpse of the intricate ritual surrounding the commemoration of death — like the death of a history in one place, and its resurrection in another.

The presumed representative of Egyptian history — the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Al-Mathaf al-Masry, the Arabic word for museum is pronounced “mat-haf”) —is something else entirely. Just like the Met, two histories joust to authoritatively articulate a certain narrative. The first vindicates the artifacts as objects of beauty and history. The second narrative is something much more nuanced, implied by the location, treatment and contextualization of these objects in the museum collection. The art objects here are signifiers of the colonial structures of power that surround their excavation and ownership. The Egyptian Museum is a hub for tourists climbing out of buses to see relics from tombs and to look at mummies and other magical things. Policemen in and out of uniform are there to protect them and gawk at their foreignness.

Then the revolution happened, and the museum was pillaged in parts. It looks out over Tahrir Square, the iconic site of the protests, upheaval and confrontations. It was in this period that burglars entered, took certain pieces and fled. It is possible that the pillaging of the museum was sanctioned to frighten people and to be used as a symbol of the lawlessness engulfing Egypt during the uprising. Or it was simple hooliganism. Of the 57 pieces missing, 29 have been found, according to government sources. If you have recently been to the museum, you can attest to the fact that display cases, where they exist, are shoddy. Glass sometimes doesn’t meet wood and locks look as if the tap of a hammer could dislodge them from their delicate fastenings.

The museum was also a site of torture. In March 2011, activists sitting in Tahrir were arrested and forcibly dragged to the museum, where they endured a number of human rights abuses. Why these deplorable acts were carried out in such a historically and culturally significant location is anyone’s guess, though proximity and the symbolic defilement of Egyptian society are both reasons that come to mind.

Egyptian artifacts form some of the most beloved and popular museum collections around the world. But what is the source of this love, and how does transferring some of Egypt's most prized relics to museums in other parts of the world lead to a certain construction of what Egyptian history means inside and outside of the country?

It is no secret that the Egyptian Museum is a mess. It is a hostile place to both Egyptians and foreigners. It is hot and overcrowded with tour groups that sometimes act offensively. It is also overcrowded with objects that are seemingly placed without any particular order, though for the uninitiated it would be impossible to say that they are even disordered because very little, if any, information is provided for the artifacts. It is a place that does a disservice to Egyptians. If this museum represents the average person’s encounter with the country’s history, it is a dismal one.

So what becomes of all of this under the new president? Egypt Independent met with museum director Sayyid Hassan to discuss the future of antiquities in Egypt and the curating of a people’s history.

When asked about the new government’s approach to heritage, Hassan said they are enacting “[the] same policy. No change at all … For example, until now they have shown good [sic] policy to us and to tourists about culture in general, and we work as usual. I think everything will be the same. We have laws. The museum will open as usual. The excavations will go as usual. Everything will be the same.”

Antiquities Minister Mohamed Ibrahim Ali visited Port Said a few weeks ago to discuss the building of a national museum there.

The locations of the new, yet-to-be opened Grand Museum in Giza and the National Museum of Civilization in Old Cairo also bring up questions of accessibility. Critics have wondered whether their locations will in fact serve to further distance Egyptian history and historical memory from the Egyptian citizen. The objects are in fact being transferred to areas better suited to tourists visiting the Pyramids, for example, or the ancient churches and mosques of Old Cairo. These actions signal a conscious and deliberate desire on the part of the Egyptian government to detach citizens from their history for the benefit of commercial tourism.

And then we have the Met in New York, a museum — like the British Museum and others of its ilk — where Egyptian antiquities are displayed with awesome respect, where marble plinths lovingly cradle the humblest of sculptures, and plexiglass cases look like fortresses with the strength to protect a thousand burial ceremonies. But the disadvantage of such a museum is that it claims Egyptian history. Its writers are not Egyptian. They are the British, French, Germans and Italians. And they not only declare ownership of these historical objects, but also erase the irrefutable presence of Egyptians in their discovery, as well as any sort of contemporary Egyptian history to justify their own presence.

One display in the Met recounts the “discovery” of the burial complex of Senwosret II in Fayoum. The careful choice of words compounds the hard work of archaeologist William Flinders Petrie, who led a team to the painstaking discovery of thousands of jewelry elements. It was hard work. But for whom?

And does only Petrie’s labor deserve mention? In another photograph showing the discovery of Hatshepsut’s statues, it looks as though at least 100 Egyptians are working to clear the site. There are many photos like this. In one summary, “A Spectacular Find,” Met curator Herbert E. Winlock is described as making “a spectacular find … During the routine cleaning of a long-known tomb thoroughly plundered in antiquity, Winlock’s crew discovered a hidden chamber.” As the phrasing of this summary reveals, it is not Winlock that makes the discovery, but the crew. Logically, at least to this author, the “crew” is much more likely to be leading most, if not all of these discoveries, yet locals will forever be remembered as the “plunderers” of antiquity while their Western counterparts are honored as heroes.

It wasn’t until quite recently that laws were implemented to properly protect Egyptian artifacts. Before the Protection of Egyptian Antiquities Law in 1983, buying, selling and pilfering antiquities was determinedly overlooked. According to Hassan, pieces were snuck out of the country before the revolution of 1952, and given as gifts by leaders and khedives. For this period, it’s impossible to claim pieces back, but for the more recent past, it’s all in the archives. If Egypt can prove that pieces have been archived and documented, they can be retrieved.

“But if the piece isn’t registered, I can’t prove it. I know it’s an Egyptian piece, but from before the revolution of ‘52 … The Louvre has more than 20,000 pieces,” Hassan explained. He said he would claim pieces like this if he had the documentation. “But our law was only passed in 1983,” he said.

One wonders if the new Egyptian museum will provide a different curatorial approach to Egyptian artifacts, considering that the history of the Mubarak regime still informs the policies and plans of curators today. As Hassan said, work will continue as usual.

Marie-Jeanne Berger is a writer and teacher living in Cairo. She contributes social commentary and art reviews to Cairo-based publications.