In an attempt to better understand the role of theater within the ongoing 25 January revolution, local playwright and theater professor Dalia Basiouny recently gave an insightful lecture titled “R for Rehearsal … R for Revolution: How the Egyptian Revolution Inspires Yet Hinders Theatrical Production.”

Basiouny is widely known for her work with feminist and activist theater, particularly through the productions created under her Sabeel Group for the Arts, which was established in 1997. In fact, many consider Basiouny to be a leading practitioner within the “free theater” or independent theater movement that swept through Egypt during the late 1980s and 1990s.

Since the start of her career, Basiouny has looked toward the possibilities within theater rather than its limitations, saying that theater “should be an act of positive consequence.”

And while independent theater is known to have a tragic list of obstacles, including an utter lack of rehearsal and performance spaces, limited resources and a great deal of censorship, Basiouny continuously discovers dynamic solutions to push theater forward.

“The lack of spaces has always been a challenge for theater groups in Egypt,” she says. “[Greater] Cairo has more than 20 million inhabitants, but there are less than 16 theaters. Therefore, one of my main concerns has always been to identify alternative spaces that people could have access to.”

In the past, Basiouny found solutions in the form of home theater, where she would present small shows in people’s homes.

“It was an experimentation on space — how do we use sound space, alternative space?” she says. “How does it affect the actor and spectator relationship?”

For her, this is not only confined to the matter of playwriting and dramaturgy, but also acting and staging. Her work often deals with women’s issues, and is loaded with the socio-political circumstances of the times.

Basiouny describes her multimedia monologue, “Solitaire,” which premiered in downtown’s Rawabet Theater in March 2011, as “the story of an Egyptian woman living in America and growing a political awareness as the world evolves around her. A thread is woven between the 9/11 attacks and the Egyptian revolution through her experiences.”

Borrowing techniques from the influential 20th-century German theater director Erwin Piscator, Basiouny’s “Solitaire” and other productions often feature technical innovations such as the use of video projections and various dramaturgical devices that disrupt conventional narratives.

The play has since been performed in close to 20 different locations, including Iraq, Germany, Morocco, Zimbabwe and the US. It is also scheduled to tour again in US and Europe at the end of March.

But while “Solitaire” continues to garner international accolade and acclaim, Basiouny has since found herself at a theatrical crossroads since the start of the 25 January revolution.

“I think of myself as an Artivist [artist and activist], a term coined by Kayhan Irani — my role as an artist and as a citizen are combined. For me, art and expression are an integral part of the revolutionary process, not just in mobilizing, but reflecting,” Basiouny says.

But during such lamentable crisis as those developed by revolutions, most notably the constant upsurge of protests and brutal violence, Basiouny and many theater practitioners she works with continue to face the paradoxical circumstances of rehearsal versus revolution.

In her lecture, Basiouny mentioned that many of her theatrical works have become interrupted and even canceled due to various protests that arise.

In March last year, Basiouny debuted her latest play, titled “Magic of Borlous,” at Cairo’s Gomhurriya Theater. The play is set in the imaginary village of Kafr Salem beside Egypt’s second largest lake, Borolus, and the play tells the story of the women in the village who gather every month to create an alternative community, which results in a disruption of the status quo and upsets the balance of power in society.

Basiouny says the play only had five performances, including three in Gomhurriya Theater, one in Minya and another in Alexandria before it was later canceled due to the frequent interruptions due to protests.

“Every time we started rehearsing this performance, another protest happened,” she says. “First, we dropped a rehearsal to join the protests at Ettehadiya [Presidential Palace]. Another time we stopped a performance in order to go to Tahrir Square, another time half of the performers were at the front lines of the Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes — eventually, we couldn’t revive the show.”

“So it’s rehearsal versus revolution. Most of the time, we opt for revolution,” she adds.

She goes on to mention that in the end, “Magic of Borolus” was only seen by close to 2,000 people, which for her is an extremely frustrating result due to the relevant and important topics the play discusses.

“While it does not take place in the standard scenes of the revolution, it captures the essence of some of our revolutionary concerns including, virginity tests, witch hunts, rumors and the role of women,” she explains.

Refusing to accept defeat, Basiouny is attempting to revive the play by using more multi-media techniques and potentially converting the form of play into a performance film to make it more accessible to a wider range of viewers.

She also came to the realization that during times of revolt, it is often easier to produce a “one-woman show” such as “Solitaire,” rather than productions with an 18 actors, like “The Magic of Borolus.”

In a later chat with Basiouny, she also discusses the role of theater in revolt. Since the start of the revolution, many of the independent theater productions have often taken a documentary form, such as Sondos Shabayek’s “Tahrir Monologues.”

Many critics say “Tahrir Monologues” was among the few plays that successfully recreated revolutionary moments and experiences on stages across Egypt.

“I do believe that documentary theater does have its role in this movement, mostly to cause reflection or action in the audience,” says Basiouny. “But putting this play aside, I would like to see practitioners break away from documentary theater as it can never fully recreate the dramatic tension of the revolution.”

Basiouny champions the idea of implementing and innovating techniques introduced by Piscator and German playwright Bertolt Brecht, in addition to Brazilian theater director Augusto Boal, with whom she trained for some time.

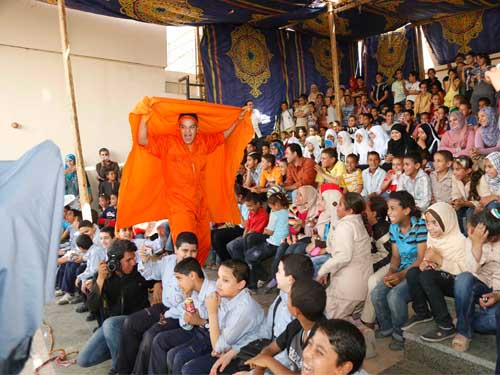

Boal is considered to be the founder of a theatrical form originally used in radical popular education movements called “Theater of the Oppressed.” His techniques used theater as a means to promote social and political change.

In this form, audiences become active participants in the performance or “spect-actors,” which allows them to explore, analyze and transform the reality in which they are living.

In their own ways, each of the above-mentioned practitioners saw revolutionary theater functioning primarily on the symbolic level, in addition to being aimed at real, political change. Their theories positioned theater as an important instrument in the social struggles of society.

“I teach many of these techniques to my theater students at [the American University in Cairo],” says Basiouny. “Usually, these forms can be presented in the forum theater or invisible theater, which works well in times of revolt because it relies more on improvised performances and spectator-interaction rather than rehearsed actors.”

She goes on to mention that some of these techniques could already be seen in various productions taking place in Egypt, most notably through Nada Sabet’s Hara TV productions.

Operating under her theater company, Noon Creative Enterprises, Sabet’s Hara TV produces interactive theater performance in public spaces to address gender and societal issues. Hara TV’s primary mission is to develop and encourage active participation in society.

Since launching in 2011, the performances have successfully toured through seven different governorates in Egypt.

For Basiouny, theater provides one means of forging a collective identity mediated through an image. She strongly believes in searching for techniques that capture the essence of the revolution rather than reducing it to a spectacle.

And while it is too soon to define theater’s exact role within the Egyptian revolution, Basiouny’s ability to infuse rituals and multimedia with feminist ideology offers one more way of framing and making sense of Egypt’s revolutionary praxis and aspirations.

“There are no certainties in this life we are currently living in Egypt. All we know is that we are alive right now, and we can each do something with the skills and passions we hold. But at the end of the day, we are living a highly improvised life,” says Basiouny.

The lecture was part of the “Cultural Seasons in Egypt: Artistic Expression & Public Discourse” program hosted by the American Research Center in Egypt.