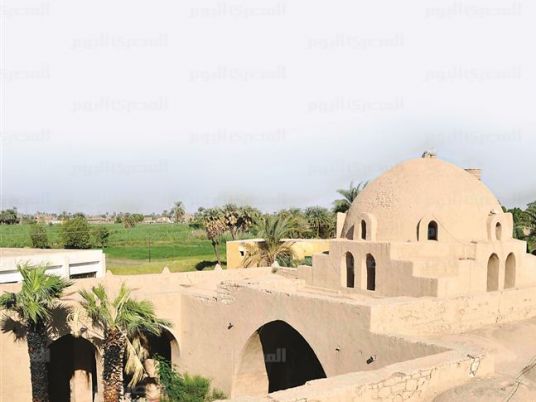

In his book “Architecture for the Poor”, Hassan Fathy called New Qurna, the village he designed in Luxor, a “hymn and a chorus of society, humans and technology.”

Building the village began in 1946 to relocate the people residing in the mountain of the old Qurna village. Fathy created a architecture that relies on cheap materials and fits the environment of Egyptian farmers.

He hoped it would serve as a model village for the the Egyptian countryside, but he did not live to see how the model unfolded.

Over the past ten years there have been calls for saving the village, but officials did not make moves until last October when the Culture Ministry announced the start of a new project to restore the village in cooperation with UNESCO. This prompted Al-Masry Al-Youm to visit the village and monitor the situation on the ground.

There are 70 houses in the village, a mosque, a marketplace, a school, a clinic and a social club, all built with mud and bricks. The houses were built in such a way so as to allow good ventilation in order to cool the rooms in the hot summer months and there are raceways under the beds in the bedrooms to prevent insects from climbing up.

“Here it is,” said the taxi driver who took us to the village. “Here is New Qurna.”

We could not believe what we saw. Save for the mosque, all the buildings were replaced with concrete structures. And there was a sign reading: This is the First House that Hassan Fathy Built. The house was surrounded by high concrete buildings.

We started our tour with the Hassan Fathy Palace of Culture where we met Ahmed al-Gamal, a young stage director. “The theater has been closed since 2009,” he said.

Gamal lives with his family in one of the concrete buildings. “We used to live in a house built in the original style with mud and bricks,” he said. “When the limestone walls started to collapse from the groundwater, my mother rebuilt it with concrete and cement.”

The theater is built in a Roman style, yet square and not circular. Its walls are all cracked, as were the walls of the mosque. We could see the sky through the wide cracks in them. Next to the mosque there is the school that was intended for teaching handicrafts. It has domes and wooden windows, all cracked to the extent that they may collapse any moment.

We roamed the narrow streets of the village looking for buildings that still bear the spirit of the architect. We stopped at Hassan Fathy’s house. Its condition was no different than the other houses.

“The government honored Howard Carter who discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun by building a museum for him,” said the guard. “But it has completely ignored Hassan Fathy, leaving his house to collapse.”

Mohamed Metawe, a resident of the village, said he had to rebuild his house with cement. “It was too small to accommodate my family,” he said, adding that he has been living here for 60 years. “I am not going anywhere. It is enough that I was relocated from the mountain once before.”

We continued walking amid the sound of barking dogs until we reached the first house that was built in the village. It belongs to Mahmoud Abdel Rady. “My grandfather was the first to move here,” he told us, explaining that the other residents were reluctant to move because they used to dig the mountain for ancient Egyptian antiquities they sold for money. “Also, they did not want to live in houses that have domes like in the cemetery.”

Inside the house we felt a cool breeze in the corridors. There are so many of them that it looked like a labyrinth. “A burglar once sneaked in to steel but got lost in those corridors,” he told us.

His father restores the other houses in the village. “I try to keep the original style but I do use modern materials,” he said, adding that there is not enough mud available after the High Dam was built. “Also, the white straw that was used to cover the walls is expensive now.”

We ended our tour, leaving behind only 15 houses that still bear Hassan Fathy’s spirit but are in bad conditions.

Political and cultural factors also played a role in changing the architectural nature of the village. After the January 25 Revolution, the restoration project with UNESCO was postponed. Also, the governor of Luxor is not allowed to undergo restorations in the village because it was declared a natural reserve and restoration work should be carried out by specialists in heritage.

The residents do not like the idea of living in houses built for the poor. That is why they rebuilt their houses with cement and concrete.

Edited translation from Al-Masry Al-Youm