Local councils are the only remaining elected bodies dominated by members of the former ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), which revolutionary forces hold responsible for corruption and now see as a counter-revolutionary force.

But as activists call for a major overhaul of the municipality system, they must take on the major challenge of changing the entire legal structure that regulates local councils’ work.

An Egyptian court is currently looking into a case calling for the dissolution of the local councils. The ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) says that it is deliberating on the best path toward reform.

Mamdouh Shahin, SCAF's legal adviser, acknowledged earlier this month in a meeting with youth belonging to various revolutionary coalitions that the local councils are overwhelmingly corrupt and dominated by remnants of former President Hosni Mubarak’s regime.

But the law stipulating that municipal elections must be held within two months of the councils’ dissolution presents a difficult challenge as Egypt prepares for parliamentary and presidential elections, scheduled for September and November respectively. With two major elections looming, elections in the municipalities may be hard for the government to manage.

Local governance in Egypt is ostensibly divided into two distinct parts. The first is the popular local councils, which are formed by elections that allocate at least 50 percent of seats to workers and farmers. The second part of municipal government is the executive council, which is composed of governors and other senior governorate staff. Members of these councils are appointed by the central government in Cairo.

There are 4496 village municipalities and 199 town municipalities in Egypt, according to official government statistics. These constitute more than 1762 local councils, with around 53,000 total seats nationally. Local councils are responsible for many aspects of local governance, like sewage, sanitation and roads. In the past, they also served as a major political organizing force for the regime.

In the last municipal elections in 2008, the NDP won more than 99 percent of the seats while opposition parties received the remainder, about 600 seats. The banned but tolerated Muslim Brotherhood boycotted the elections after being allowed to compete for only 20 seats.

The widely-criticized Local Administration's Law 43/1979, which essentially submitted local councils to Cairo’s control, reflects Egypt’s tradition of centralized planning and state-led development at the expense of local governing bodies.

The law gives less power to the elected local councils than it does to the executive councils, since it only authorizes elected members of the local councils to supervise governorates and municipalities. Elected members of the local councils also have the right to oversee district budgets and make suggestions, comments and inquiries to governors. However, these powers are subject to constraints by the central government.

“The way the law was drafted doesn’t guarantee that the elected member has even a consultative role. The elected members only discuss the budget, which is controlled by the central government,” said Peter Nabil, a liberal Wafd Party member of the local council in Nuzha district in the Heliopolis neighborhood of Cairo.

Other politicians argue that elected members cannot supervise how the budget is spent.

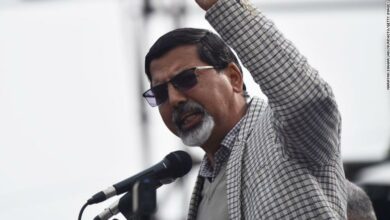

“There is a major problem, which is the budget of the executive municipalities is really small and subject to corruption. You have the right to discuss the budget of a district but then you don’t have a clue about what will happen with it,” said Muslim Brotherhood figure Saad al-Katatny, who is the newly appointed secretary general of the Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party.

Generally, 10 to 15 percent of national budgets, including the most recent draft budget released by the interim Finance Ministry, is allocated for municipalities. Most of the money goes to infrastructure and other municipal services, in addition to salaries and wages for municipal employees.

“Transportation sectors, water and sewage get the lion’s share of public expenditure at the local level, which is estimated at more than 80 percent of the local budget,” wrote Abdullah Shehata, professor of economics at Cairo University in a recently published study.

Critics say that the local councils became more concerned with receiving funds from the central government than working on local development. This, the critics say, is because the budget was drafted and agreed upon by members of the NDP. Central government officials would exchange money and favors from local government officials.

“[The budget] was issued and drafted by provincial governors and officials of executive councils who are members of the NDP. It is supposed to be discussed by the elected members, who are also members of the same party,” said Katatny. “That tells you the problem: the government is debating itself.”

“This system is designed to serve the former regime. The idea of decentralized decisions and giving the grassroots a voice is completely ignored,” said Nabil.

Elected members of local councils have no power to determine how local revenue is raised, which mainly comes from motor vehicle registrations and store and building licenses; nevertheless, the council members use their posts to pursue personal interests and take part in illegal profiteering. Last December, the Central Auditing Organization (CAO) published a report saying that the scale of corruption in the local councils exceeded LE258 million in one year. CAO said that the corruption is centered on obtaining illegal licenses for building properties or giving illegal permits to build new floors in existing buildings.

“In our local council, I rarely saw people debating about the budget. They are all concerned about getting benefits from the councils, especially getting licenses for buildings and stores,” said a former NDP local council member of Bulaq al-Dakrour who asked not to be identified. Many claim that local council members obtain licenses for bribes.

“Those licenses serve the member either by providing him illegal money or by giving him a circle of support in the district by which he can run in the parliamentary elections,” said Intissar Badr, a leftist political activist.

Problems of Egypt’s local governance have recently attracted international attention. USAID, the US government’s development organization, launched a program called the Egyptian Decentralization Initiative to assist the Egyptian government in developing strategies and initiatives for fiscal, administrative and political decentralization.

During last month’s G8 summit in Deauville, France, Western leaders told Egypt’s interim Prime Minister Essam Sharaf that they would offer aid packages contingent on decentralization.

But if the need for municipal reform is clear, the means for doing so is less so.

The Muslim Brotherhood favors dissolving the local councils, but says that municipal elections should be delayed until after the presidential election.

“I’m totally against the law regulating the local councils, but at the same time the elections should be put off until the second half of 2012,” said Katatny. “I think all the political powers are busy now with the upcoming elections.”

Some secular forces call for conducting elections after changing the whole system’s constitutional and legal framework. Presidential hopeful Mohamed ElBaradei last month called for drafting a new constitution before parliamentary and presidential elections.

“Most of the forces that heralded and maintained the revolution haven’t organized into political groups that could compete in elections. Therefore we need to draft the constitution first and then change the laws and then conduct the elections, whether parliamentary, presidential or local,” said Ghada al-Bayaa, member of the Central Committee of the leftist Tagammu Party.

According to Bayaa, Egypt’s political landscape in needs time to develop. For the local elections, time is needed for the youth who took part in the popular committees during the revolution to start becoming active in politics.

Activists say the popular committees produced community leaders who are able and willing to serve the community.

Amr Saad al-Matany, 30, who hails from the working-class district of Bulaq al-Dakrour, is one of those emerging community leaders currently campaigning for his local council.

“I took part in the popular committee and after the revolution we, the youth of Bulaq, established a committee with representatives from every street to tackle the issues of the whole district; through this committee we’ve decided to run for the local elections,” he said.

“We are not NDP members. We stay with the people all the time,” said Matany, hinting at the tendency of NDP politicians to physically disappear from the communities they represented once elected.

“Who’s better than us in representing the district?” asked Matany.