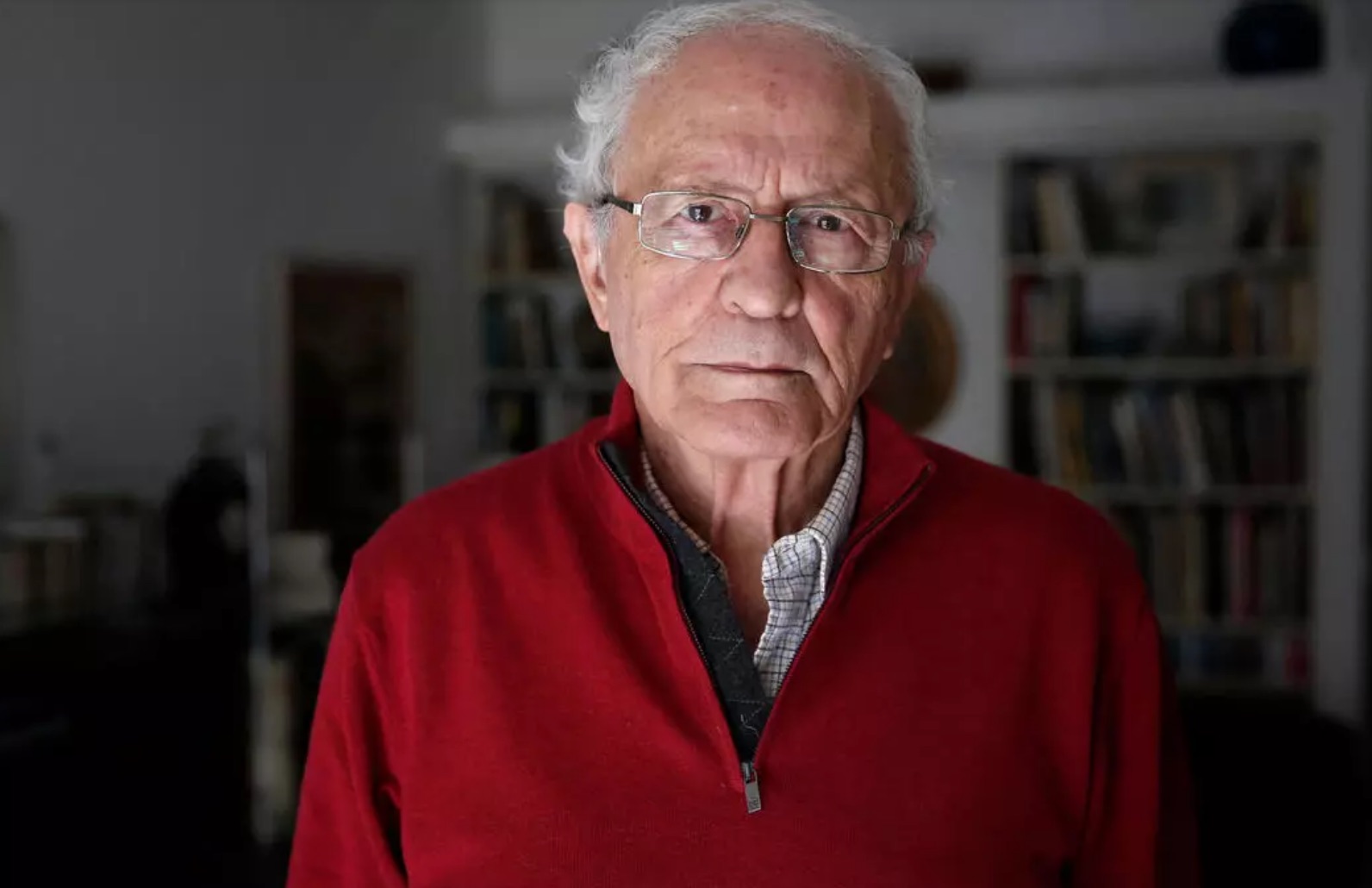

“Today I lost part of my life. Farewell, Samer,” scholar Amr Abdel Rahman wrote of of his longtime friend Samer Soliman, who family, friends, students and readers lost Sunday after a battle with cancer.

Soliman’s death at a critical juncture in the history of Egypt, a nation he lived of and for, has shaken many. As a scholar, an intellectual, an activist, a teacher and a friend, he lived a life of continual giving.

Soliman led a thorough academic life, traveling between different degrees, the last of which was a PhD he received in political science from the Institute of Political Studies in Paris in 2004. His scholarly path was always outward-looking, transcending the boundaries of academic institutions. He lived the life of an engaged activist and political organizer, who tactfully hoped and genuinely believed in change. He mediated his intellect on the editorial pages of newspapers and through the endless conversations we had with him as journalists and scholars.

Soliman’s scholarship was stimulated by a curiosity of the institution of the state and its mechanisms of survival through the internal machinations of the ruling regime. His seminal work, “Strong System, Weak State,” questioned the former regime of President Hosni Mubarak’s handling of financial woes while preserving its political position, examining in particular the grave effects of shallowly conceived policies such as international borrowing, otherwise described by scholar Mostafa Hefny as “the temporary stitching of the growing cleavages in the workings of government.”

In his more recent work, “The Autumn of Dictatorship,” Soliman further explored the roots of revolution in the consistent weakening of the state apparatus, which limited political freedoms while financial resources were dwindling. Soliman argued that by investing in a robust security apparatus, the former regime, though remaining strong for three decades, left behind a weakened state. The work can be read retrospectively, but also as a document for the future, with the current government of the Muslim Brotherhood venturing to reproduce the duality of limiting freedoms while running out of economic alternatives.

Mirroring this concern with government policy-making, Soliman was interested in the view from the other side, or otherwise the “social infrastructure of political change.” This interest transcended the confines of academic work, and translated itself into his activism, social engagement and political organizing.

In his lifetime, Soliman was concerned with envisaging the possibilities of a democratic experience within an authoritarian environment. Throughout the process of interrogating these possibilities, Soliman was at the heart of several important initiatives. He co-edited Al-Bosla, a journal whose title literally translates as “the compass” and which became a platform for poignant conversations about how democracy can be born to the very specific conditions of historical development in Egypt.

He also co-founded “Egyptians Against Discrimination,” moved by his passionate battle against sectarianism and other forms of discrimination. While many have submitted to the notion that sectarianism has grown to become an inherent sentiment in our society, Soliman recalled a moment in history that powerfully disputed this notion: The 1919 anti-colonial movement in Egypt framed national identity around the battle against British occupation, in which religious identity became only a parcel of this identity. Commenting on the incident of Erian Youssef Saad, a Christian activist who attempted to kill Youssef Pasha Wahba, Christian pro-occupation prime minister back in 1919, he jokingly noted: “To prove that you are truly Egyptian before being a Copt, you will have to start by killing a Copt.”

His longtime friend and activist Akram Ismail recalled how Soliman spoke of his upbringing by a leftist father, during which time he never sensed the pains of sectarianism until he stepped outside the confines of his household.

“Samer departed, leaving behind his bitterness from sectarianism and his long struggle for a more humane society,” Ismail wrote. “We will miss you.”

Soliman’s death leaves us alone in a turbulent moment, but armed with all the thoughts and energy with which he filled us. His death makes us wonder about the future he often thought of, but did not get a chance to see. And above all, his death reminds us of the eternal challenge of struggling so much to live a life ultimately rendered ephemeral by the abrupt moment of death.