Ramadan is a time of fasting, self-restraint, and good deeds. It is also an occasion for storytelling, either in celebration of the nightly feast or as a way to pass the time. In the spirit of the long days and longer nights of Ramadan, Al-Masry Al-Youm shares stories and tips for a good month in a new series called “Alf Leila We Leila: Stories for Ramadan Through the Ages.” Throughout the holy month, we will post original pieces from the Al-Masry Al-Youm staff on everything from how to host a perfect iftar to reports of Ramadan abroad, alongside Arabic literature from Sheherazade to Mahfouz.

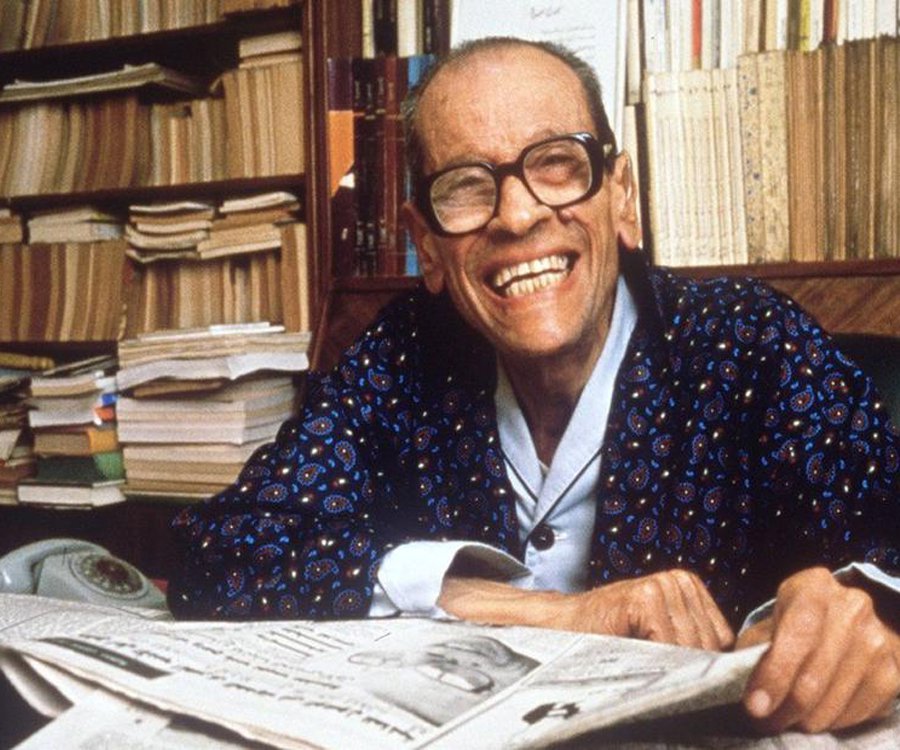

Below, Al-Masry Al-Youm discusses Naguib Mahfouz's The Dreams, a collection of short prose from the beloved, late Egyptian novelist.

In 1994, following an assassination attempt by Islamic extremists, the great Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, the author of over thirty novels and hundreds of short stories, found himself unable to write. The stabbing had left his right hand permanently damaged and the writer, who has been compared to Dickens and Tolstoy, could only work for a few minutes each day.

It would be almost ten years before Mahfouz would publish a new book; 2005’s The Dreams (AUC Press), a collection of very short stories on the quotidian and the surreal, are all transcriptions of the novelist’s dreams. But in spite of their length and their living slightly or very outside of the real world, Mahfouz is true to his roots as a storyteller and unrivaled illustrator of Cairo, a city which, being so erratic and evocative and downright chaotic, is always, in part, a dream world.

Mahfouz lived his last years under the protection of a bodyguard. So, like Sheherazade, he was vividly aware that at any moment his life might end, and he marked each night with an unfinished story.

Some involve journeys. In “Dream 83,” Mahfouz rides with an “enchantress” in a stallion-drawn cart high above the Great Pyramid, leaping out when the pyramid is within reach, his eyes trained on his companion who “becomes fixed in the heavens as a luminous star” as he falls.

Some are about family. “Dream 80” sees mother cautioning son, “You have to account for yourselves as well; don’t try to tell me it was all written and decreed.”

Many are about love. Mahfouz did not marry until 43, and his dreams seems to have been somewhat preoccupied by two varieties of a life's loves: those missed and those lost. In “Dream 39,” he is manipulated into offering a proposal of marriage to a young woman, who tells him he, “was no longer a young man, and that my life was being wasted on mere reflection.” In spite of being cornered into the deal, he is not unhappy.

“Dream 40” tells the bitter story of generosity backfiring when the narrator, a boy with the book’s mature and contemplative tone, takes in an “extraordinarily lovely and miserable girl” only to be accused of crimes against her.

Many of the book’s dreams are on the brink of being nightmares, but not all the disasters are instantly noticeable. In “Dream 79,” a man waits anxiously in a hotel for his girlfriend, only to discover her swimming happily with other men. He cannot swim himself and tries to learn from the hotel’s manager who tells him, “don’t surrender to sadness,” and the pain of her small betrayal is eclipsed by the “limitless joy” the man feels when she greets him later. But, as in good fiction, the pain of the dream is visible best to those reading. When the man’s girlfriend speaks her sad, final line, telling him, as they shop and wander in what he considers to be a return to normalcy, “We don’t have enough time,” and the scorned lover misinterprets her words, the reader sees it for what it is: an effort, willful or not, to remain unaware in order to preserve his own, temporary happiness.

Mahfouz narrates his own tale of potential “barmecide” when he, in “Dream 80,” writes about approaching a literary benefactor in her “reception hall, whose beauty and vastness dazzled me,” only to have the “enchanting figure” point a small pistol at him, causing him to faint. Whether or not, when he awoke, the woman rewarded him for his response with a meal and literary patronage, the reader will never know; true to the unpredictability of dreams, Mahfouz’s often end abruptly.