Naguib Gobrail, a lawyer and the head of the Egyptian Union of Human Rights Organizations (EUOHR), has called for the protection of Egypt's Copts from what he described as increasing violence from Salafi groups.

“Copts feel like strangers in their own country; many are being forced to leave Egypt as a result,” Gobrail told journalists during a press conference at the Cairo headquarters of the EUOHR.

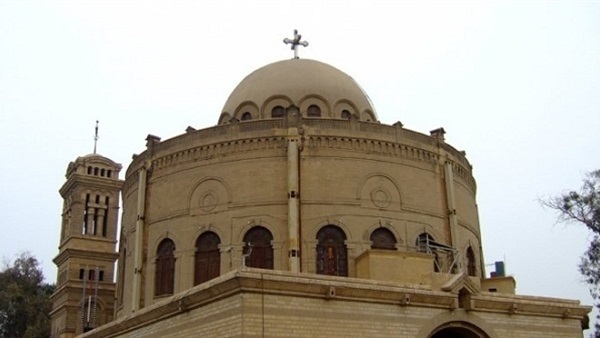

Held under the title “The Cry of Copts,” the press conference was held two days after the St. George Church in Marinab, Aswan was attacked by a group of Muslims and part of it gutted by fire.

Gobrail, an outspoken defender of Copts, who has at times attracted controversy for allegedly exaggerating their plight, angrily condemned the governor of Aswan and demanded his removal for “misleading the media and public opinion and causing sectarian discord.”

Aswan Governor Mostafa al-Sayed appeared on television after the Marinab attack and said that the custodians of the St. George Church were just as much at fault as their attackers because they had broken building regulations by constructing a dome more than four meters tall.

Legal restrictions on the construction of churches have long been a complaint of Egyptian Christians, who believe that laws on church construction are discriminatory.

One audience member described Sayed as a “thug.”

Gobrail situated this attack in what he described as a “systematic policy of ethnic cleansing” by Salafi groups targeting Copts, making reference to two attacks on churches since the 25 January revolution and incidents of Christian girls being forced to wear veils in public schools.

During the press conference a mobile phone video of the February attack on the Atfeeh Church in Giza was shown. Gobrail asked why the authorities claim that they do not know who was responsible for the attacks when individuals in the video are clearly identifiable.

The EUHRO head also questioned why “no one has been held to account for attacks against Copts, while the perpetrator of an attack against a Jewish synagogue in Cairo [in 2010] was imprisoned for seven years.”

“State bodies do not treat Copts as well as extremist elements in society,” Gobrial said.

“It is as if we [Egyptian Copts] were not part of the revolution,” he said in reference to the sectarian violence since the revolution.

Priest Refat Fekry said that “the law, education and statements by Muslim clerics” have contributed to the spread of attacks on Copts, citing the vast difference between the law governing the construction and repair of churches and that regulating the construction of mosques, which imposes far fewer conditions.

Fekry demanded that Muslim preachers who incite violence against Copts on television face criminal prosecution.

He also called for the release of imprisoned blogger Maikal Nabil, “on an equal footing with Loai Nagati and Asmaa Mahfouz.”

Nagati, an activist, was released in July after being tried in a military court, while Mahfouz, another activist, was interrogated by the military prosecution office last month but charges against her were dropped. Both activists are Muslims.

Nabil, a Copt, is currently on hunger strike in protest at his imprisonment, and his family claim that he has been denied access to the medications he normally takes for a heart condition.

“Nobody can blame Copts if they seek recourse to international treaties ratified by Egypt when all the doors here are closed,” Gobrail said, warning that Copts will boycott the upcoming parliamentary elections if they continue to be targeted “in this extremist Salafi climate.”